TWE Remembers: The Pentagon Papers

By experts and staff

- Published

By

- Guest Blogger for The Water's Edge

Sunday is the fiftieth anniversary of the New York Times’ publication of the Pentagon Papers. My colleague Margaret Gach, a research associate for U.S. foreign policy at the Council on Foreign Relations, volunteered to recount the story of how the Times came to possess the classified documents, triggering a legal battle that produced a landmark Supreme Court decision on the freedom of the press.

A constant tension exists in any democracy between the government’s need for secrecy to conduct sensitive operations and the right of the people to know what their government is doing. When the press publishes classified—or simply embarrassing—government information, that tension can trigger litigation. The past decade has seen its fair share of consequential leaks, such as Edward Snowden’s disclosure of National Security Administration secrets. And just this week ProPublica published secret tax information revealing how U.S. billionaires have avoided federal income taxes. But it was fifty years ago from Sunday that Daniel Ellsberg’s leak of the Pentagon Papers shocked the country and sparked one of the most important First Amendment rulings in U.S. history.

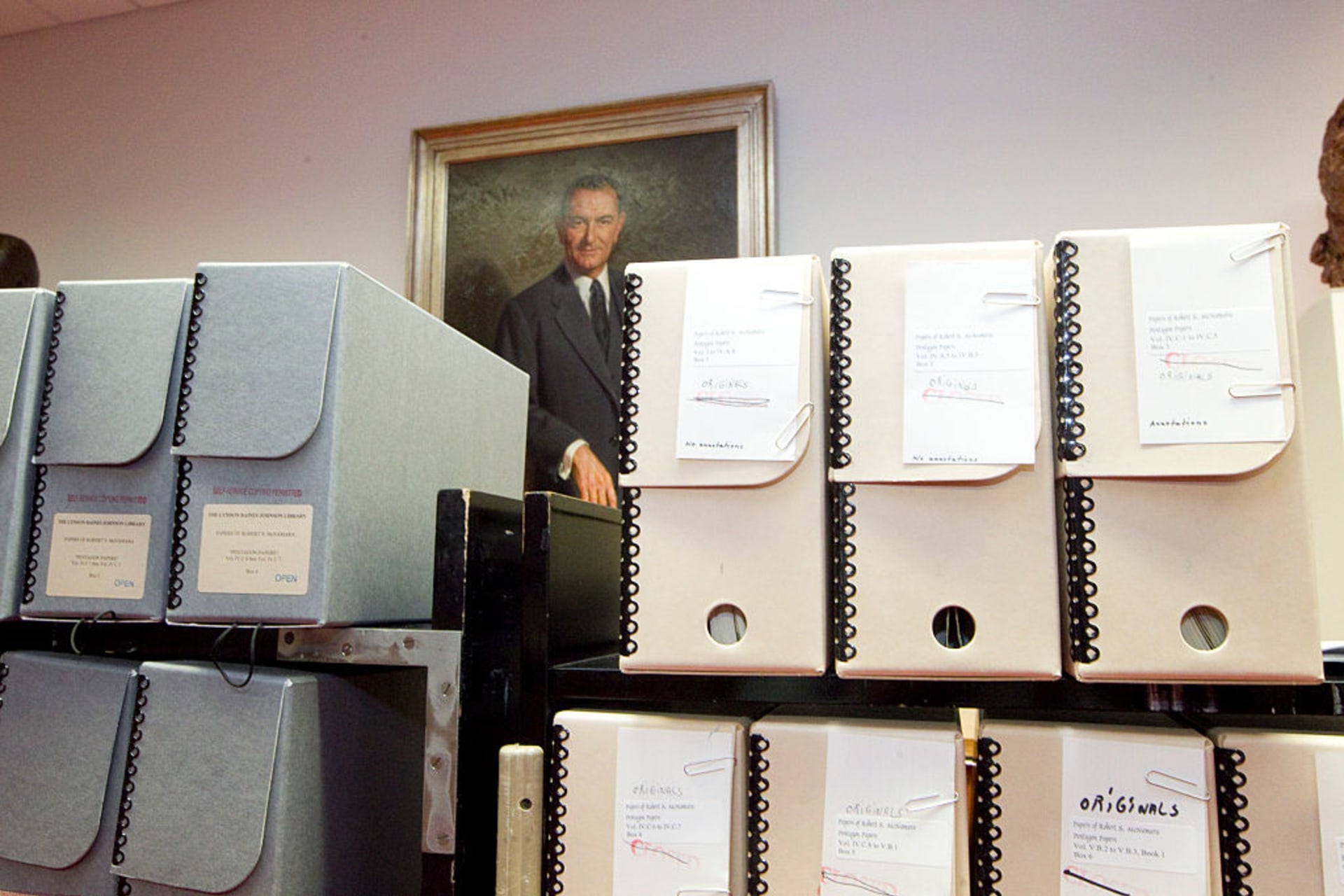

On June 13, 1971, the headline “Vietnam Archive: Pentagon Study Traces 3 Decades of Growing U.S. Involvement” dominated the front page of the Sunday New York Times. Reporter Neil Sheehan’s story revealed the existence of a top-secret, 7,000-page government study outlining how the United States had intervened in Southeast Asia and Vietnam since the end of World War II. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara had commissioned the study in 1967 after becoming disillusioned with the prospect of success in the Vietnam War. The task force was headed by future CFR president Leslie H. Gelb, then-director of policy planning and arms control for international security affairs at the Pentagon. Gelb recalled that McNamara wanted a team to sift through documents that could answer the ‘’dirty questions.” Those questions included whether civilian or military leaders were lying to each other and the public about the realities of the war and if U.S. victory was even achievable.

Not even President Lyndon B. Johnson knew of the clandestine project. Under Gelb’s direction, it grew into a broader historical analysis, with a team of three-dozen military officers, historians, and defense analysts, including Ellsberg. They collected thirty to forty cabinets worth of documents for their analysis, such as memos from the Joint Chiefs of Staff, CIA studies, State Department files, and McNamara’s notes.

Sheehan reported that those documents revealed a longer and deeper level of U.S. involvement in Vietnam than Americans had been told: Harry Truman had provided significant military aid to the French fighting in Indochina beginning in 1950. Dwight D. Eisenhower decided to oppose a communist takeover in South Vietnam, undermining the 1954 Geneva Convention. John F. Kennedy had supported the overthrow of South Vietnam dictator Ngo Dinh Diem and shifted U.S. policy toward Vietnam from a “limited-risk gamble” to a “broad commitment.” Johnson had begun planning for overt war while campaigning on a promise of limited U.S. involvement. And for years, the government’s optimistic assurances to the public had not reflected policymakers’ growing doubts that the war could be won or if it was worth the price in blood and treasure.

On January 15, 1969, Gelb completed the “Report of the Office of the Secretary of Defense Vietnam Task Force.“ The study spanned forty-seven volumes, with 3,000 pages of analysis and 4,000 pages of appended documents. Just fifteen copies were made.

Ellsberg was a former Marine and RAND Corporation analyst who had spent two years in South Vietnam with the State Department. He had originally supported U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War, but by 1969 had become convinced it was unwinnable. By the start of that year, roughly 37,000 U.S. troops had died in the fighting, and public discontent was growing. (The total death toll in the war would be 58,220 U.S. troops and an estimated 2 million Vietnamese civilians and one million Vietnamese soldiers.) Ellsberg thought that the Pentagon Papers could boost the momentum of the antiwar movement. In October 1969, Ellsberg and his colleague Anthony Russo began sneaking out portions of the report from a RAND safe to photocopy.

Ellsberg first approached National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger and members of Congress like Senator J. William Fulbright (D-AK) and Senator George McGovern (D-SD), urging them to enter the report into the public record. When they declined, he turned to Sheehan. In a 2015 interview, which the Times reporter permitted to be released only after his death six years later, Sheehan recounted that Ellsberg had given him permission to take notes on the report, not copy it. But while Ellsberg was on vacation, Sheehan snuck the volumes from his apartment. The process of photocopying 7,000 top-secret pages wasn’t made any smoother when the machines of the first copy shop crashed under the strain. (Sheehan retroactively got Ellsberg’s permission to use the full documents a few weeks before they were published.)

Sheehan and a team of Times staff prepared their series on the Pentagon Papers in secret in three adjoining rooms of the Hilton hotel. Ellsberg learned just a few hours in advance that the Times was ready to publish. Sheehan, meanwhile, admitted to ignoring Ellsberg’s phone calls until it was too late to stop the presses.

When the Times hit stands that Sunday, President Richard Nixon was originally pleased with the story’s criticisms of Kennedy and Johnson. But his mood turned when his assistant for domestic affairs John Ehrlichman, White House Chief of Staff H.R. Haldeman, Kissinger, and Attorney General John Mitchell argued that the leaker should be discredited and swiftly prosecuted to prevent embarrassment to Nixon’s own administration.

After the second day of articles—headlined, “Vietnam Archive: A Consensus to Bomb Developed Before ‘64 Election, Study Says”—Mitchell sent a note warning the Times to stop publishing excerpts from the report or face prosecution. The Times ignored the warning. After the third day, the Justice Department asked a New York district court for a temporary restraining order and a longer-term preliminary injunction against further publication, citing “grave and irreparable” damage to the United States if the Times continued publishing the excerpts.

The U.S. government had previously restricted free speech in times of war. The Sedition Act of 1798 criminalized “false, scandalous, or malicious writing” during the U.S. naval war with France; the Lincoln administration prosecuted disloyal speech during the Civil War; and the Espionage Act of 1917 and Sedition Act of 1918 targeted critics of the Great War. But for the first time, the Nixon administration sought to block publication beforehand on the grounds of national security, not just prosecute the publishers after the fact. New York district court Judge Murray Gurfein granted the temporary restraining order but rejected the request for a longer preliminary injunction, writing,

The security of the Nation is not at the ramparts alone. Security also lies in the value of our free institutions. A cantankerous press, an obstinate press, a ubiquitous press, must be suffered by those in authority in order to preserve the even greater values of freedom of expression and the right of the people to know.

With the Times stymied by the restraining order, Ellsberg turned to the Washington Post. After a day of “bedlam” pouring over the report and debating the legality of publishing it, the Post published its first installment on June 18: “Documents Reveal U.S. Effort in ’54 to Delay Viet Election.” A DC district judge at first refused the government’s request to block the Post from printing further excerpts. However, an appeals court barred the Post from publishing on June 20 pending a fuller hearing. Ellsberg continued to leak the report to newspaper after newspaper around the country, which the Justice Department soon stopped trying to block.

The cases against the New York Times and the Washington Post quickly moved to the Supreme Court. There the government argued that publishing the classified documents threatened national security and infringed on the president’s power to direct foreign policy. On June 30, four days after oral arguments, the court ruled six to three in New York Times Co. v. United States in favor of the Times and the Post. Justice Hugo Black wrote in a concurring opinion,

The press was protected so that it could bare the secrets of government and inform the people. Only a free and unrestrained press can effectively expose deception in government. And paramount among the responsibilities of a free press is the duty to prevent any part of the government from deceiving the people and sending them off to distant lands to die of foreign fevers and foreign shot and shell.

The Times and the Post resumed publishing extracts from the Pentagon Papers the next morning. The Times’ coverage won it the 1972 Pulitzer Prize for public service. Five decades later, the Post would follow up with the “Afghanistan Papers,” describing how successive administrations misled the public on the war in Afghanistan.

The Pentagon Papers leak heightened Nixon’s paranoia of a left-wing conspiracy bolstered by the media to unseat him, setting him on a hunt for enemies of his administration that would culminate in the Watergate scandal and his resignation. He discussed plans to steal Gelb’s copy of the Pentagon Papers from the Brookings Institution, where Gelb was a senior fellow, though the burglary never materialized. The charges against Russo and Ellsberg, who had been indicted on June 28, 1971, under the Espionage Act, were dropped in 1973 after the judge declared a mistrial. The Watergate investigation had revealed that Nixon’s infamous “plumbers” burglarized Ellsberg’s psychiatrist’s office to steal embarrassing information.

Ellsberg’s leak did not significantly hasten the end of the Vietnam War. Nor did the Pentagon Papers provide a complete historical record of the war—for example, Gelb’s team didn’t conduct interviews or have access to White House correspondence. The Pentagon Papers’ lasting legacy, rather, is the power it shifted toward the press in the enduring tug-of-war between the fourth estate and the government.

Still, the Supreme Court’s ruling only prohibited the government from imposing prior restraint, not prosecuting leakers or publications after the fact. The Obama administration used the Espionage Act to prosecute eight leakers, more prosecutions than all other previous administrations combined. Likewise, the Trump administration secretly tried to seize reporters’ phone and email records to identify who had leaked national security information to the press. President Joe Biden recently announced that prosecutors investigating leaks will no longer be allowed to obtain journalists’ records to find their sources. But as the U.S. media, technology, and security landscape grows even more complex, the tension between a government’s secrecy and the public’s right to knowledge isn’t likely to be resolved any time soon.

Here are a few other resources to learn more about the Pentagon Papers:

- Forty years after the Pentagon Papers were first released, the National Archives published the unclassified report in full.

- The New York Times published a special report of essays looking back at the Pentagon Papers’ publication for the fiftieth anniversary.

- Columbia University President Lee Bollinger and University of Chicago law professor Geoffrey Stone coedited a collection of essays by leading scholars and journalists on the Pentagon Papers’ legacy, National Security, Leaks and Freedom of the Press: The Pentagon Papers Fifty Years On.

- Director Steven Spielberg told the Washington Post’s side of the story in The Post (2017), starring Tom Hanks and Meryl Streep and nominated for Best Picture. You can watch it on Amazon Prime, Google Play, or YouTube.

- Rick Goldsmith and Judith Ehrlich’s documentary on Ellsberg, The Most Dangerous Man in America: Daniel Ellsberg and the Pentagon Papers (2009), was nominated for the Oscar for best feature documentary. You can stream it on Vimeo.

- The first chapter of legal scholar David Rudenstine’s 1998 book, The Day the Presses Stopped: A History of the Pentagon Papers Case, outlining the creation of the study, is online here.