Vietnam and the United States Make Nice for Now, but Disappointment Looms

By experts and staff

- Published

Experts

![]() By Joshua KurlantzickSenior Fellow for Southeast Asia and South Asia

By Joshua KurlantzickSenior Fellow for Southeast Asia and South Asia

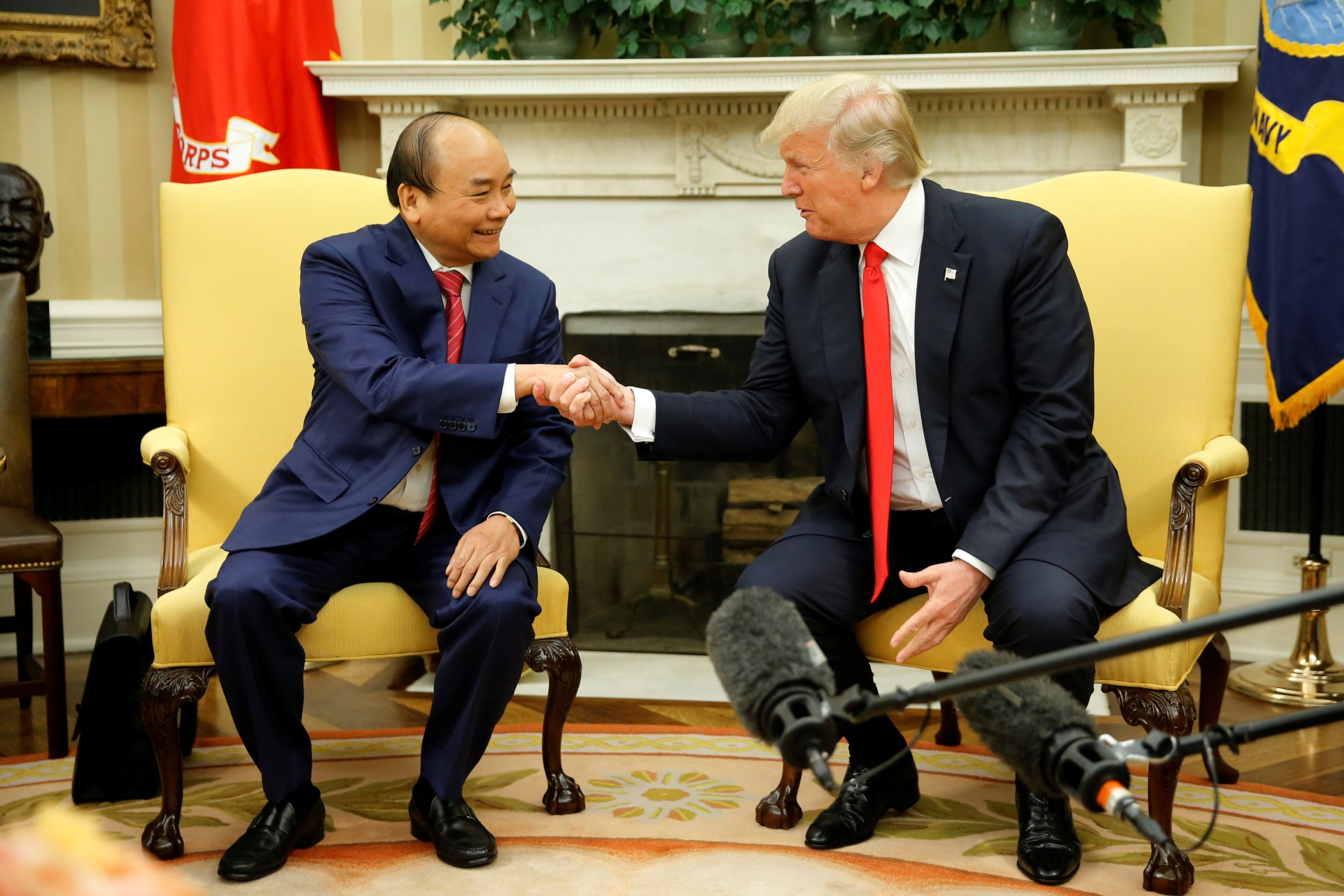

This week’s visit of Vietnamese Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc to Washington resulted in the usual readout of supposed achievements and breakthroughs. The prime minister seems to have understood that this U.S. administration likes foreign officials to arrive in Washington with promises of new investments and other deals that the White House can quickly tout as a win.

And indeed, during the visit the U.S. president boasted that the two nations were signing deals that would result in “billions” in new trade, as well as, supposedly, creating many new jobs in the United States. At a speech at the Heritage Foundation, Vietnam’s prime minister promised roughly $15 billion in new deals. Reuters noted, however, that the Commerce Department’s figure for how much the deals would be worth was about one-half the Vietnamese prime minister announced in his speech.

Still, President Trump declared, “They (Vietnam) just made a very large order in the United States—and we appreciate that—for many billions of dollars, which means jobs for the United States and great, great equipment for Vietnam.” The two sides further discussed strategic issues, such as Vietnam’s desire to buy more cutters; Hanoi is hardly going to follow the lead of the Philippines and back down from its assertive defense of its exclusive economic zones in the South China Sea.

But this fanfare covers up some major problems in the relationship. The amount of deals announced is unlikely to fully please the U.S. administration, even though Hanoi likely sees the deals, in a way, as a concession to make to please the White House. And Vietnam will almost surely continue to run a major trade surplus with the United States. For an administration that looks at surpluses and deficits in a zero-sum way, trade relations are going to continue to be a primary irritant in the relationship.

Even on Tuesday, with the Vietnamese prime minister in attendance at an event, according to the Wall Street Journal, “U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer appeared to tag Vietnam as a country unfairly benefiting from trade by selling more to the U.S. than it buys. Mr. Lighthizer emphasized a $32 billion U.S. trade deficit with Vietnam while introducing Mr. Phuc at an event for businesses.”

Indeed, trade hawks in the U.S. administration are likely to continue to view Vietnam warily, and the Vietnamese prime minister received little in the way of concrete action on trade from the U.S. side during his visit. It’s easy to imagine U.S. officials continuing to publicly push and shame Hanoi to try to reduce the U.S. trade deficit with Vietnam in some way. U.S. defense companies could seek significant deals in Vietnam, which is rapidly modernizing its armed forces, but Hanoi is not going to shift extensively to U.S.-made systems anytime soon, as much of its weaponry is dependent on Russian systems, which Vietnam has relied upon for decades and which Vietnamese officials are comfortable with.

What’s more, Hanoi’s leaders and the leaders of ten other nations could well move forward with the Trans-Pacific Partnership without the United States, signaling a further unmooring of Vietnam and the United States’ trade approaches in the Asia Pacific. This does not mean that Vietnam will become even more dependent on trade with China, but it would mean that the trade strategies of Hanoi—which is also negotiating with the European Union—and Washington will continue to further diverge.

Vietnam’s prime minister also supposedly came to Washington with the idea that the two countries could, sometime in the future, negotiate a bilateral free trade deal, according to the Wall Street Journal. But such a possibility seems far off—even U.S. officials admit it is a low priority compared to many other potential deals and renegotiations. And in any case it is hard to imagine the two countries generating enough goodwill on trade issues in the next few years to move toward a bilateral deal.