More on:

There is no single definition of manipulation, to be sure—so no way of definitively answering the question. Over the last ten or so years, manipulation has been equated with "buying foreign exchange in the market to block appreciation." That definition is certainly built into the criteria laid out in the 2015 Trade Enforcement Act. But “buying reserves to block appreciation” wasn’t hardwired into the 1988 act, which has a much more elastic definition of manipulation.

Yet even if the 2015 Trade Enforcement Act isn’t the only possible definition of manipulation, it still provides a bit of guidance - as President Trump implicitly recognized today: "Mr. Trump said the reason he has changed his mind on one of his signature campaign promises is that China hasn’t been manipulating its currency for months."

The thresholds of being called out for "enhanced analysis" that the Treasury was required to set out in the 2015 act aren’t perfect—no measures are. The threshold for the bilateral trade balance is genuinely problematic. It lets small countries with a propensity to intervene in the foreign exchange market off the hook for one. And even if you think there is sometimes valuable information in the bilateral trade data (many don’t), the bilateral balance really should be assessed on a value-added basis.*

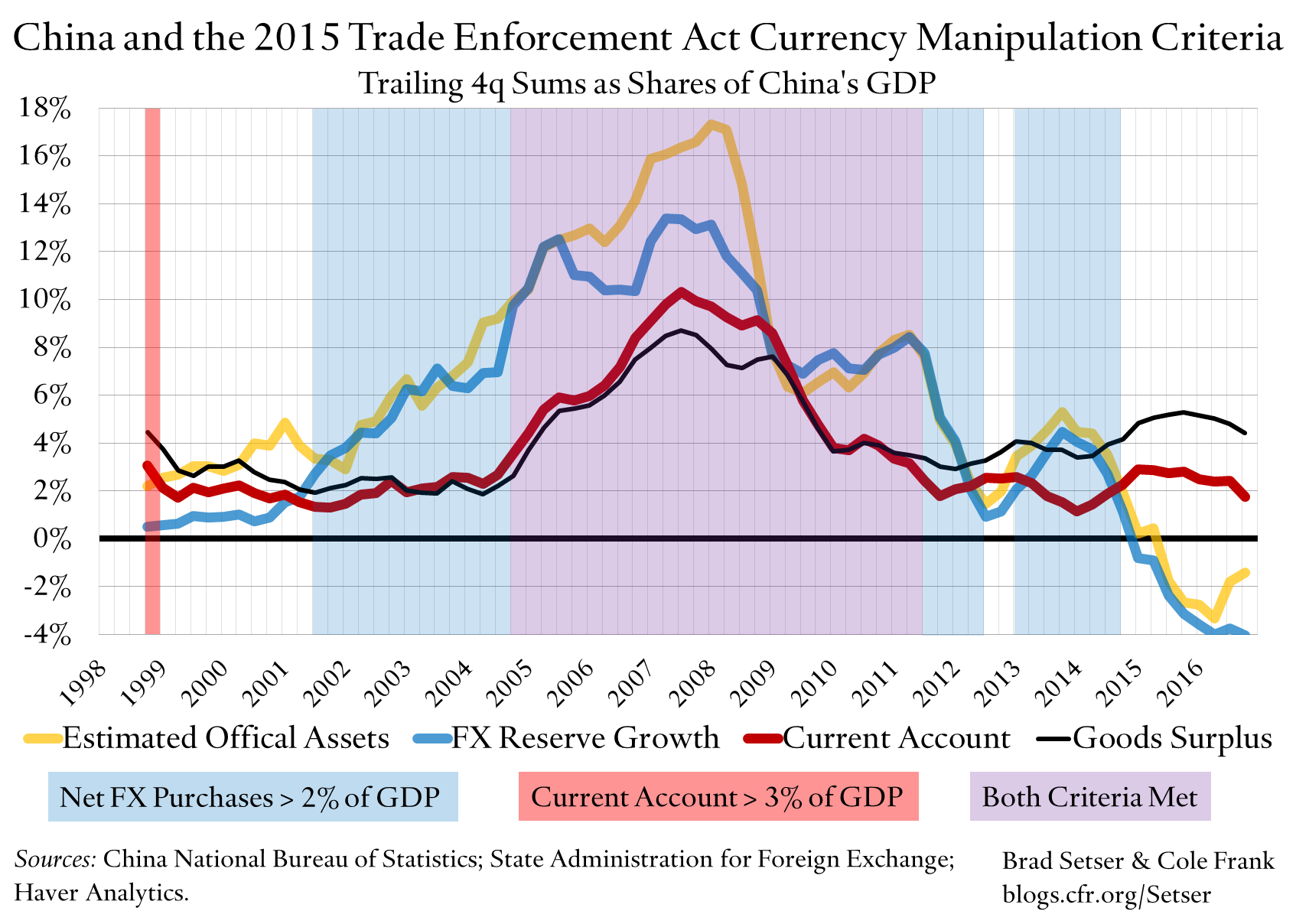

But the current 3 percent of GDP current account surplus and 2 percent of GDP in intervention thresholds are certainly reasonable. Those criteria show that China should have been singled out for “enhanced engagement” from 2005 to roughly 2012, but not since.

But all criteria can be gamed. And I worry a bit that China has been revising its current account data with the goal of keeping the headline external surplus down—it is hard to overstate the number of times the details of China’s services data have been revised since 2014.***

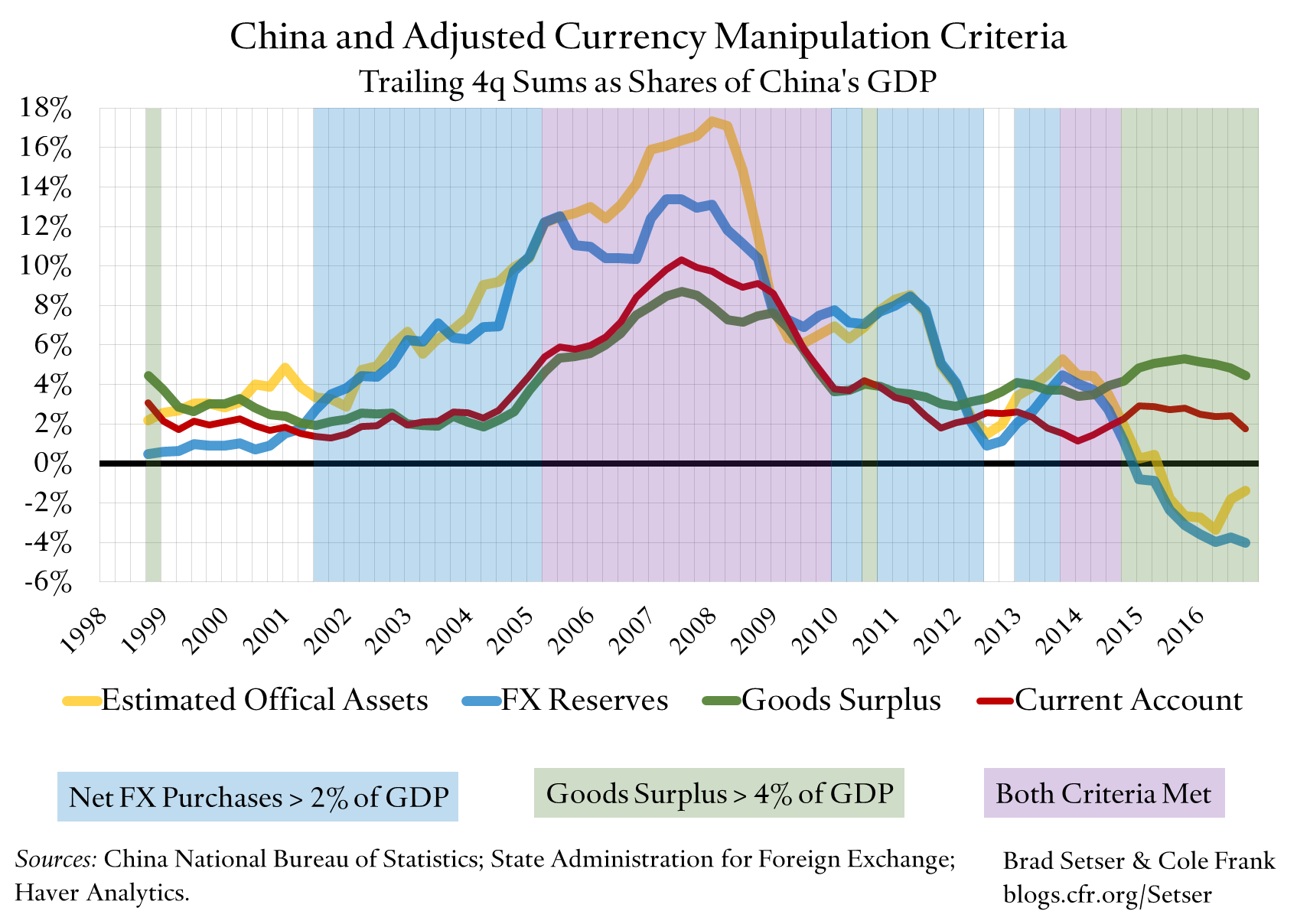

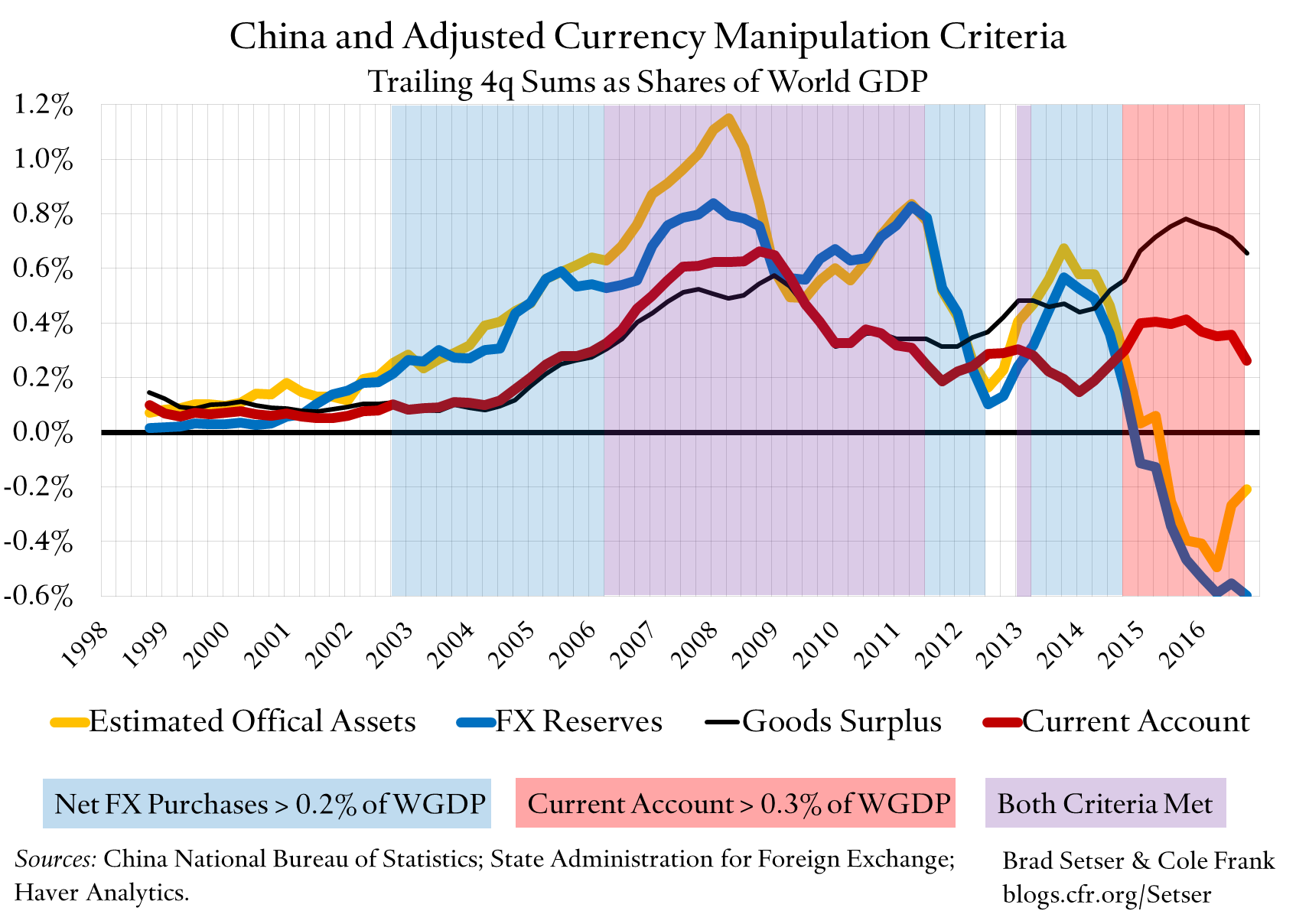

So Cole Frank and I looked at what would happen if some of the Treasury criteria were changed, or more realistically, augmented.****

For example, looking at China's overall goods surplus alongside the current account surplus might sense if you have doubts about the current account numbers. China's good surplus was a bit over 4% of its GDP in the last four quarters of data (4% of China's GDP is close to $500 billion, a significant sum).

Or you could China’s surplus relative to global GDP to try to get a sense of how China's surplus is impacting its trading partners (a better measure is world GDP ex China, but doing that takes a bit more effort, especially if you intend to track more than one country). That also could put China’s current account surplus back in the zone of concern:

But, as the Trump Administration now seems to recognize, there is no realistic way of getting around two facts: (1) China recently has been selling not buying reserves, so its intervention mechanically has served to limit the pace of depreciation, and (2) both China’s goods surplus and its current account surplus are heading down, so the Chinese overall policy stance isn't obviously impeding balance-of-payments adjustment.

All this said, I would note that nothing tends to burn through reserves quite like a controlled depreciation. A significant portion of China’s reserve sales are a result of the fact that China has managed its currency in ways that helped generate the expectation that it wanted a gradual weakening of its currency. If China can stabilize expectations (and limit outflows from the state banks), its reserve sales might fall off fairly quickly.*****

* There are data limitations here. The last OECD numbers on Chinese value-added in Chinese exports (around 70 percent) are from 2011. Things have changed since then, with Chinese value-added rising relative to China’s total exports. More and more high-end components are now made in China, even if they are not made in China by Chinese firms (see Bob Davis and Jon Hilsenrath of the WSJ; "China, once an assembly platform that sucked in commodities and manufactured goods from abroad, put them together and reshipped them, is now producing much of what it needs domestically. Benjamin Dolgin-Gardner, founder of Hatch International Ltd., an electronics manufacturer in Shenzhen, China, says he now uses Chinese-made LCD screens rather than ones made elsewhere in Asia for the tablets he produces. Memory chips for MP3 players are also made in China rather than imported from Japan and South Korea"). The famous Apple example now deceives—the relevant concept here is China’s share of total manufacturing value-added, not China’s share of the profit on the sale of an iPhone. Fun factoid: the New York Times reporting suggests that iPhones for sale in China are technically made offshore, in a bonded zone, then exported to Ireland (in a legal sense) before being legally imported into China from the bonded zone after downloading the needed software from Ireland (or wherever Apple now has parked its “global” IP rights)…an interesting example of modern global value chains.

** Japan and the NIEs (South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore) all also have larger overall external surpluses, relative to the size of their economies, than China now does. So in this case the bilateral value-added deficit maps to the imbalances in the global BoP.

*** China's service deficit initially was in other business services. Then the 2015 tourism numbers were revised up, with jumps in tourism imports, exports and the tourism deficit. Then the revisions were extended back to 2014. And most recently the numbers were revised again, so not there is no upward jump in tourism exports -- only a jump in imports. The revisions have been linked to a broader change in how China collects its tourism data, with more reliance on electronic payments numbers and less on the numbers reported by China's tourism trading partners. There are of course innocent explanations for these revisions: almost all services data is a bit suspect in real time and is revised as better measures come in. But it is also clear that the net result of after all the various revisions was a big jump in the services deficit in 2014, just when the goods surplus was starting to rise on the back of Europe’s recovery and lower commodity prices. And given the methodology now used to calculate tourism imports has created a significant gap between China’s tourism imports and its counterparties' tourism exports, it seems likely that China’s current account balance now includes at least some financial transactions that really should be counted as financial outflows (such a reallocation would reduce the services deficit, and increase the current account surplus).

**** The Trade Enforcement Act statute allows the Treasury to set out its own quantitative thresholds, but requires that the Treasury perform "an enhanced analysis of macroeconomic and exchange rate policies for each country that is a major trading partner of the United States that has-- (i) a significant bilateral trade surplus with the United States; (ii) a material current account surplus; and (iii) engaged in persistent one-sided intervention in the foreign exchange market."

***** I also have great confidence in the ability of China's authorities to engineer official outflows that would substitute for reserve growth should China start buying foreign exchange in the market. I consequently doubt that China will ever trigger the 2% of GDP in reserve growth threshold. But that is a topic for another time.

More on: