Why Hasn’t China Needed to Intervene More This Year?

The prospects for moving from a three month truce to a more durable ceasefire and eventual resolution of the current trade conflict with China have become a central focus of global markets.

The issues that need to be sorted out are too complex to be addressed in full in ninety days, but it is certainly possible that enough progress could be made in the next ninety days to allow both sides to decide to continue the negotiations.

I personally hope that the administration’s focus on structural issues will go beyond the structural issues that have impeded investment in China by U.S. firms. Letting more U.S. firms invest in China on their own terms—and not just on China’s terms (through a JV, often with tech transfer)—is important. But it won’t do much to expand the number of manufacturing jobs supported by exports to China—doing that requires making it possible for U.S. firms to export to China, not just for U.S. firms to produce in China to sell in China. Finding a deal that tears down the barriers to selling more American made capital goods, which are often bought by state firms whose management is appointed by the party, is in some ways harder than finding a solution to concerns about IPR theft, or even tech transfer (which would be structurally addressed by lifting the JV requirements).

Concretely I suspect that this means seeking commitments from China to offset the trade impact of its (non-negotiable, I assume) industrial policy in civil aviation on U.S. exports, and making sure that China is open to imports of things like U.S. made medical equipment. Autos, I fear, are now a lost cause.* U.S. exports of manufactures to China haven’t been growing since 2012—and over a long-time horizon, they have grown more slowly than China’s economy.**

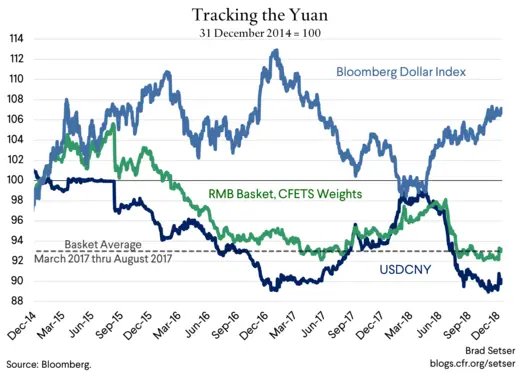

I also assume that an informal part of the current “pause” is a “pause” in Chinese depreciation, even as China’s own economy slows. A weaker yuan wouldn’t create a conducive atmosphere for negotiations. And, well, I think the yuan is still something that China effectively manages.

By managing the flows that are allowed to keep the market in equilibrium.

By sending signals about the price that the Chinese government wants to see in the market. The counter-cyclical factor in the daily fix being the most obvious.

And by buying or selling foreign currency as needed—or instructing the state banks to do so on its behalf.

The only real question is whether China is ultimately managing against the dollar (and thus intent on defending seven to the dollar) or managing against a basket.

Or managing against the dollar at some times and the basket at others, depending on its needs of the moment.

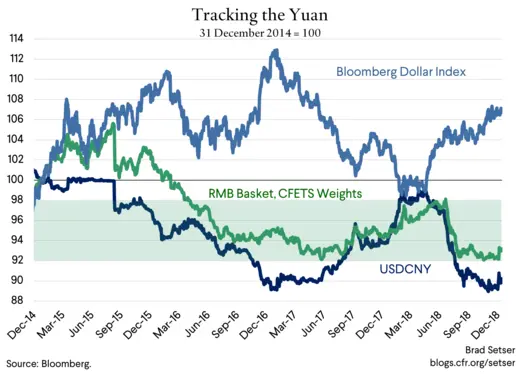

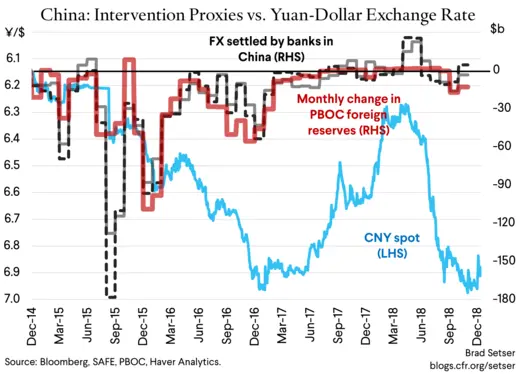

For now, I think the facts still fit best with “management against a basket”—with the yuan allowed to float in a narrow band around an undeclared central point vs. the basket (see the chart above), but with active intervention (see the swings in the settlement data below) as needed at the edges of the band.

But it is striking that many active in the FX market believe that China ultimately is still targeting the dollar-yuan (dominant currency pricing and all, and, well, seven still seems to be an important number) rather than the basket.

The settlement data for October and the rise in headline reserves in November suggest that the amount of actual intervention needed to keep the yuan inside the basket has been pretty modest recently. Surprisingly modest in fact, as in the past downward moves in the yuan have triggered large-scale outflows.

So modest that some think that there is a bit of hidden intervention (state banks borrowing dollars through the swaps market e.g. swapping yuan for dollars and then selling the dollars and buying yuan spot to support the yuan). See Mike Bird of the Wall Street Journal in late October. I though haven’t (yet) found a smoking gun that clearly points to more intervention then net sales of $50b in settlement data since July.

And more generally, I am struck by the fact that the flow of foreign exchange in and out of China, while regulated heavily, now seems to be fairly close to balance.

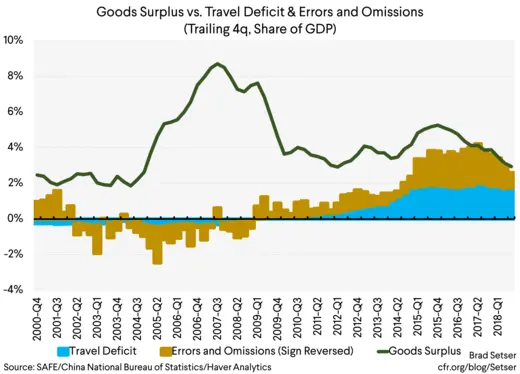

The current account for one is far closer to balance than it has historically been. That reflects some one off factors—China’s willingness to allow large scale outward tourism (and to look the other way if this leads to some backdoor financial outflows), the 2018 rise in oil prices, the 2018 rise in memory chip prices, higher iron ore imports after supply side reforms shut down some low quality, polluting Chinese production. But for now the measured current account is close to balance, and the goods surplus basically covers the services deficit from tourism and “hot” outflows.

I am not as convinced as the market that China’s current account will swing into deficit next year—at least so long as the trade truce remains in place. Falling oil and semiconductor prices are almost certain to slow the growth in China’s imports next year. Note that the overall trade surplus (and the surplus with the United States) rose amid weak trade in November.

And the financial account also looks relatively balanced—

I think that reflects three or four things:

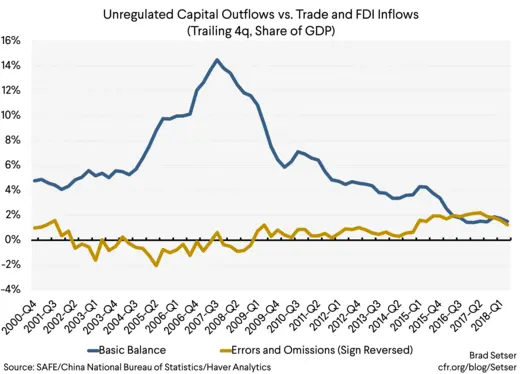

- “Hot” outflows through errors and omissions are pretty close to the “basic balance” (the sum of the current account plus net FDI flows). This took a bit of work—China had to crack down on the currency speculation embedded in the FDI outflows from the Anbangs and HNAs and Wanda’s of the world. But China did that in early 2017, and that led to a structural improvement in the basic balance of around $100b a year.

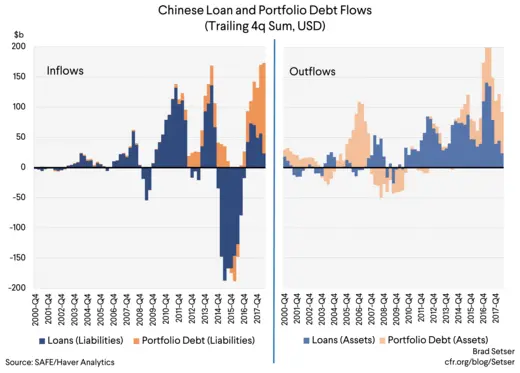

- The controlled opening of China’s financial account to portfolio flows has attracted a real inflow—$150b in bond inflows in the last four quarters of data.

- The state banks have been able to borrow abroad to finance their lending abroad. So far—and the data here is still patchy—the yuan’s move this summer doesn’t look to have led to a large reversal in bank flows. My guess is that’s because the nature of the bank flows has shifted. Back in 2015, the inflows were funding carry trades (Chinese firms wanted to borrow in dollars, because they could then sell the dollars and hold higher yielding yuan assets). The more recent inflows look to have financed the dollar lending of the state banks. Though they may also have funded some leveraged firms squeezed out of the yuan funding markets by the deleveraging campaign.

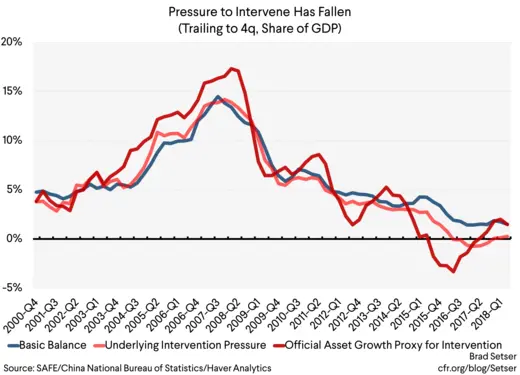

The net result is that, gulp, as long as all of the conditions above hold, the “structural” need for China to intervene heavily has fallen.

The current account plus net FDI flows*** covers the leakage from Chinese capital flight (in errors and omissions). And the gap between those two numbers is still a good predictor of “true” intervention.****

And it will remain a good proxy for the intervention need so long as the formal, measured, and largely regulated part of the financial account basically balances.

Inflows through regulated channels (the bond inflows) and through offshore borrowing by regulated entities (the state banks) has roughly matched the outflow associated with the build of foreign assets by the state banks. The banks have been buying bonds offshore and building up some potential ammunition if they are called on to intervene, and they also have been supporting the belt and road.

Which means, at the end of the day, that the flows in China’s foreign exchange market seem to be in rough balance at the current exchange rate—and that as a result it doesn’t take a ton of effort (or intervention) for China to keep the yuan where it wants the yuan. So what matters for the market (for now) is less the flows and more the politics.

And so long as the negotiations with the United States are ongoing, I suspect (or perhaps just hope) that the politics will push the Chinese to keep the yuan from testing new lows.

* BMW is the largest exporter of cars and SUVs from the United States to China. And China recently let it obtain majority control of its JV as a sweetener to get it to raise its Chinese production. Mercedes now wants a bigger stake in its JV as well. (For high margin cars and SUVs, the JV requirement effectively acts as a tax, one that encouraged imports rather than Chinese production). Plus, Keith Bradsher’s reporting suggests that the U.S. auto companies have no economic incentive not to use their existing Chinese supply chain to supply the Chinese market. In fact, at current exchange rates, I suspect they increasingly have an incentive to use their Chinese supply chains to meet global demand.

** In my view, the current Chinese economic policy that most directly threatens a large number of American jobs is China’s desire to build its own civil aviation industry. Something close to a quarter of Boeing’s narrow body output is now exported to China. Civil aviation accounts for $130b of U.S. exports, or well over 10 percent of the United States‘ total manufactured exports. Yet so long as subsidies for domestic Chinese production and “buy China” preferences in civil aviation aren’t on the negotiating table, the future of America’s most important source of manufactured exports to China depends either on a bet that China’s civil aviation sector won’t produce a viable competitor any time soon, or on a bet that the Chinese plane will be so dependent on a U.S. aeronautics supply chain that there won’t be a major net loss of jobs. Despite some new JVs.

*** The FDI inflow here is mostly imputed as it reflects reinvested earnings, which is also a debit on the current account, so in some sense it is a “fake flow”—but no matter, think of the goods surplus funding the tourism outflow and errors and omissions.

**** My broad measure tries to pick up the growth in the foreign assets of CIC and the state banks as well as the increase in the PBOC’s formal reserves. It is based on four lines in balance of payments which I believe are dominated by state institutions.