India’s 2024 General Election: What to Know

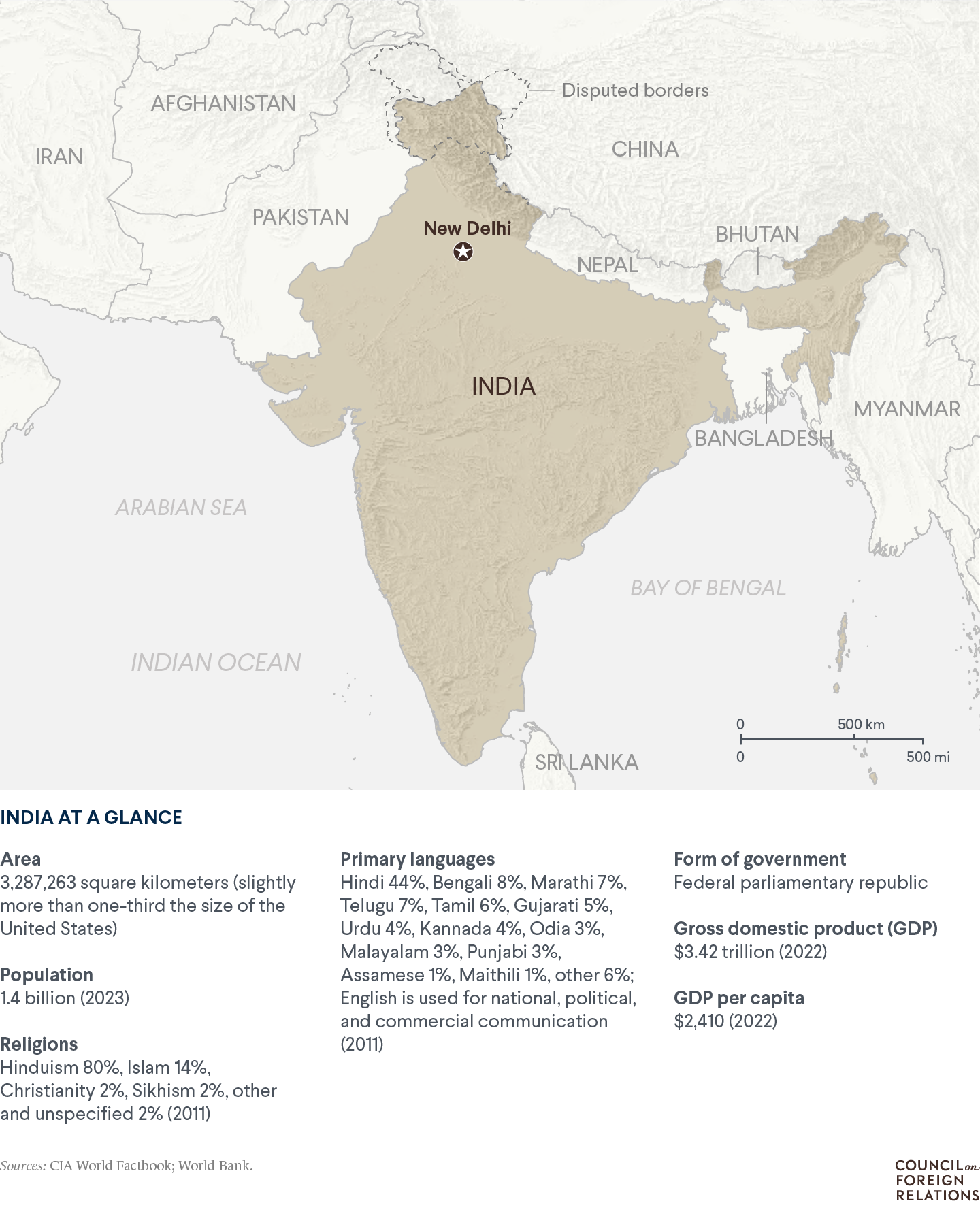

The election date for the world’s largest democracy is set to begin April 19 and last six weeks. What would the results of a third term for Prime Minister Modi mean for India’s economy, democracy, and position in the Global South?

April 2, 2024 1:15 pm (EST)

- Expert Brief

- CFR scholars provide expert analysis and commentary on international issues.

Who are the major contenders to watch in these elections?

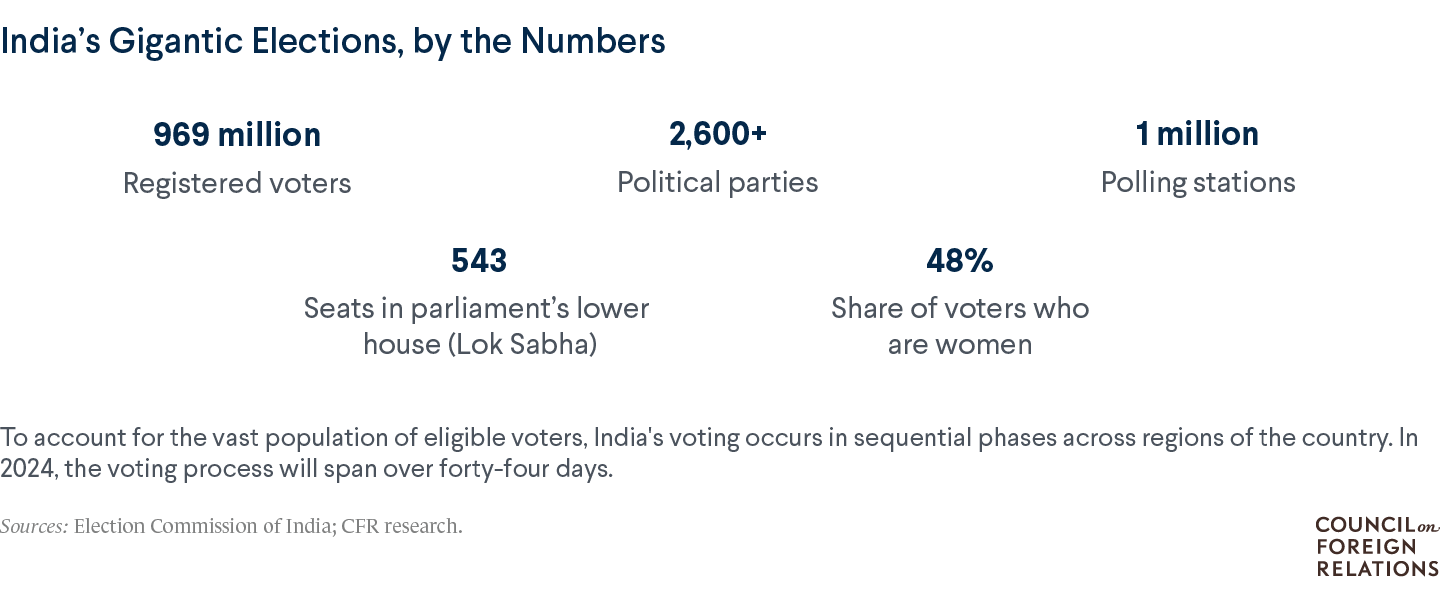

India has a multiparty parliamentary government with a bicameral legislature. This year’s elections—set to begin April 19—are for India’s lower house of Parliament, the Lok Sabha, which has 543 seats. The party or coalition of parties that wins a majority will nominate a candidate for prime minister and form a ruling government.

Currently, the BJP rules with a coalition known as the National Democratic Alliance (NDA), Recent opinion polls heavily favor the BJP, Modi, and many of their allies to remain in power. The main challenge to the BJP is led by the Indian National Congress, or “the Congress” as it is popularly known, which is the only other party with a cross-national appeal. However, the Congress lost dismally in the previous two national elections, held in 2014 and 2019.

More on:

To contest the 2024 elections, the Congress has formed an alliance known as the Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance (INDIA) with a large number of regional parties, such as the All India Trinamool Congress, the current government in the state of West Bengal. But the coalition could be cracking. The All India Trinamool Congress has objected to the Congress’s insistence on putting forth its own candidates for many seats, including in states such as West Bengal, where the Congress is less popular among voters. Furthermore, one of the architects of INDIA—the state of Bihar’s chief minister, Nitish Kumar of the Janata Dal (United) party—has defected to the BJP-led coalition.

After the Election Commission of India completes the complex electoral calculations needed to decide who won the elections, the president of India will invite the winning party to form a government, and the party’s leader will be appointed prime minister. If no single party is able to win an outright majority, the leading party will form an alliance with smaller parties. As evident from the NDA and INDIA, alliances are often formed in advance of elections, though they can shift before or even after them. Modi is poised to remain the predominant face of the BJP, while politician Rahul Gandhi will likely represent the Congress party’s opposing coalition. This leaves voters (who cannot directly vote for either) with a binary choice between two representative figures.

What are the main issues driving voters’ concerns in these elections?

There are several significant issues in these elections, and they can often vary from state to state. Some major concerns for voters are:

More on:

Unemployment. Across all of India, much buzz has been made of the country’s youth bulge, but many Indian youth are in fact left unemployed in a market that prioritizes highly skilled labor. At the end of 2023, the unemployment rate among youth ages 20–24 was 44.9 percent, while the overall unemployment rate stood at 8.7 percent.

The economy. In agrarian states such as Punjab and Uttar Pradesh, the rising debt of farmers and their subsequent protests has been an ongoing issue. More than 40 percent of India’s population is dependent on agriculture, and farmers feel left behind in India’s quest to raise living standards. Farmers’ demands include raising their stagnating incomes and setting price floors that guarantee farmers a 50 percent profit from government purchases of certain crops. The health of the Indian economy is also at stake. On one hand, India’s gross domestic product (GDP) grew by 8 percent in 2023. But on the other, economists have argued that this growth does not accurately reflect India’s lack of progress on the Human Development Index (HDI), a UN-developed tool that measures a country’s development based on a combination of factors, including average life expectancy, income, and education level. They note that declining private consumption spending and contracting government consumption spending are worrying trends and say that other issues, such as unemployment and growing inflation, are cautionary signs behind India’s economic growth.

Welfare programs. The BJP government has made its delivery of a new kind of welfare program central to its campaign. Governments typically supply public goods to their citizens, such as rudimentary health care and elementary education. But the Modi government has engaged in what economists, such as former Chief Economic Advisor Arvind Subramanian, have called “new welfarism.” That is, the Indian government has been subsidizing the provision of essential private goods such as electricity, housing, bank accounts, and cooking gas, as well as giving out cash payments. Furthermore, the creation of a digital public infrastructure system has allowed the government to eliminate middlemen and transfer many benefits directly to voters. For example, mobile banking allows the government to directly pay citizens with cash transfers. Thus, the strength and continuity of the kinds of welfare programs spearheaded by the BJP will be an important issue.

Why is there fresh controversy in India surrounding Hindu-Muslim relations and Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s January inauguration of a Hindu temple at the site of a torn-down mosque in the city of Ayodhya?

Hindu-Muslim relations are playing a clear role in the general elections. In personally inaugurating the temple even before it has completed construction, Modi was attempting to consolidate his Hindu voting base. The inauguration of the temple—on the land believed to be the birthplace of the divine Hindu warrior-king Rama—marked the delivery of a long-ago promise made by the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) to restore the glorious Hindu past. It was celebrated as a momentous occasion across many parts of India, with school closings, half-days off work for national government employees, and huge Modi and Rama cutouts displayed everywhere.

Similarly, fault lines between India’s Hindu majority and its Muslims, the country’s largest religious minority, can be seen in the government’s decision to begin enforcing the 2019 Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA). Announced last month, the implementation of the CAA allows non-Muslim religious minorities from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Pakistan to apply for Indian citizenship. The BJP had campaigned on promises to implement the law, which it argues will protect religious minorities such as Hindus, Sikhs, Christians, and Buddhists from persecution. Critics contend that it deliberately excludes Muslim minorities who also face persecution, such as the Hazara community in Afghanistan or Shiites in Pakistan, and that it sets religious criteria for citizenship.

Furthermore, critics charge that the CAA, when combined with India’s National Register of Citizens (NRC), will result in the expulsion of many Muslims. The registry allows the government to identify and expel undocumented Indian residents. However, many poor residents who have lived in the subcontinent for generations have little to no documentation. This is a particularly acute issue for women, who are often excluded from ownership and inheritance documents because property and land are passed to male heirs. Thus, critics have pointed out that undocumented Indian Muslims could be rendered stateless by the registry and then blocked from citizenship by the CAA. For example, the Indian government contends that the NRC can help identify undocumented immigrants in the state of Assam, where about twenty million people have migrated from Muslim-majority Bangladesh. But a preliminary draft of the NRC excluded as many as four million Indians in the state who claimed they were, in fact, citizens. In theory, non-Muslims in Assam could apply for citizenship through CAA, but Muslims would have no such legal recourse.

In addition to the ongoing controversy about the rights of minorities, are controls on the media and the increase of disinformation on social media signs of democratic backsliding in India?

Indian democracy is paradoxical. India holds regular, largely free and fair elections with high levels of voter turnout. In 2019, nearly 67.4 percent of Indians voted in the national elections. Furthermore, organizing elections for an electorate of more than nine hundred million people is no small feat. Indians cast votes electronically, meaning that election workers have to ensure that voting machines are present and monitored countrywide, including in geographically challenging and remote terrain. For example, Anlay Phu, located at more than 16,000 feet (4,877 meters) above sea level, has one of the highest-altitude polling stations in the world, with less than a hundred registered voters.

However, the BJP government has been accused of rolling back civil liberties in India, including by cracking down on the famously outspoken media. These policies, combined with the global expansion of disinformation across social media, has India watchers worried about the strength of Indian democracy.

How would another Modi term influence India’s foreign policy? Would it have a bearing on the country’s efforts to stake a role as a leader of the informal grouping of developing countries known as the Global South?

While Indian foreign policy has had continuity between governments, Modi has certainly put his stamp on many aspects. The BJP government has promoted India’s global role by balancing a wide variety of seemingly clashing and delicate interests. In the Middle East, India has formed strong relationships with Arab nations as well as Israel. India also leads the biennial multination naval exercises known as Milan; this year, the navy of India’s close strategic partner, the United States, participated in Milan alongside the navies of Iran and Russia, two countries with whom India has long had cordial relations.

India’s projection of its balancing role has also positioned it to claim a leading position among Global South nations. At the Group of Twenty (G20) summit in 2023, India suggested that it had the ability to champion Global South interests and build bridges with the West. Moreover, Modi has heavily advertised his own prime ministership to his domestic constituents as being instrumental in bringing about India’s prominent position. This bridging role—which can be expected to continue under a third Modi term—has been noticed both domestically and internationally. Modi enjoys much popularity among voters as the champion of India’s national prestige, but the reception globally has sometimes been less laudatory. For example, India’s adversary, China, called Milan an exercise in “vanity” without any substance (“面子”和“里子”都想要).

Will Merrow created the graphics.

Online Store

Online Store