Roxanna Vigil is an international affairs fellow in national security at the Council on Foreign Relations. Her public service career spans fifteen years in the area of U.S. foreign and national security policy toward Latin America.

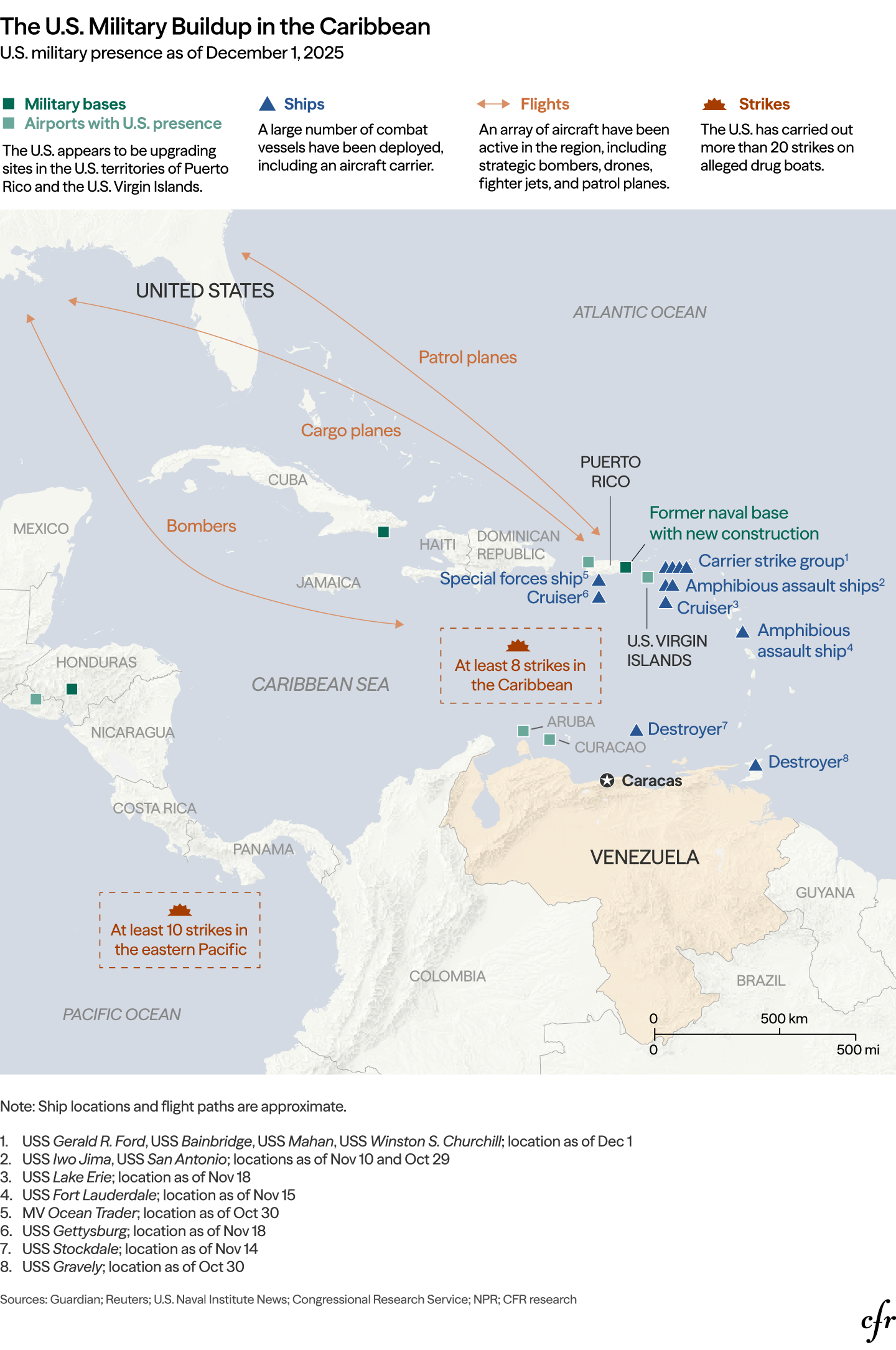

The U.S. military buildup off the coast of Venezuela that began in August was followed by U.S. strikes on more than twenty alleged drug boats that left over eighty people dead. Across three months of deadly boat strikes, the Donald Trump administration has increased pressure on the Nicolás Maduro regime with the arrival of the USS Gerald R. Ford, the U.S. military’s most advanced aircraft carrier, to the Caribbean Sea; the designation of an alleged Maduro-led cartel as a foreign terrorist organization; and the president’s repeated threats of future land strikes ostensibly to combat drug trafficking.

More on:

Despite reports that Trump had ordered a pause in diplomatic negotiations with Maduro, communication between the Venezuelan regime and the United States has continued. The president confirmed on December 1 he had a phone call with Maduro. Prior to the call, Trump had said he was open to talking with Maduro, remarking that, “If we can save lives, we can do things the easy way—that’s fine. And if we have to do it the hard way, that’s fine, too.”

Doing things the hard way could mean war with Venezuela. This would be a mistake. It would also be inconsistent with Trump’s National Security Strategy that discourages direct intervention to achieve its goal of a “reasonably stable and well-governed” Western Hemisphere. U.S.-imposed regime change through force would likely lead to chaos and ultimately weaken the Venezuelan opposition, which has grown prominent under the leadership of María Corina Machado—the 2025 Nobel Peace Prize winner. The United States has not unilaterally achieved regime change through air power alone, and a ground invasion remains unlikely.

Instead of pursuing further conflict, the Trump administration should focus on using its military deployment to bring Maduro to the negotiating table. As the major power interested in Venezuela’s future, the United States has at various times served as both a catalyst and an impediment to negotiations between the Maduro regime and the Venezuelan opposition since 2014. Drawing on the lessons learned from these efforts will be critical to securing a deal and preventing further escalation.

Negotiations floundered without U.S. involvement

The United States is shifting from a behind-the-scenes supporter of Venezuela’s opposition to a direct participant in negotiations due to the recent military buildup. In negotiations with the Maduro regime during the last decade, the opposition has sought to restore democracy through credible elections with international observers. These talks were often strained because of divisions within the Maduro regime and opposition, as hardliners on both sides tried to sabotage negotiations to undermine the moderates that sought dialogue. But the talks failed, in part because the United States was lukewarm in its support or outright opposed them.

More on:

The four efforts that failed between 2014 and 2019 include:

2014 UNASUR-Vatican dialogue. The United States did not directly support this effort, which was sponsored by the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR) and supported by the Vatican, Brazil, Colombia, and Ecuador. It took place amid widespread antigovernment protests in Venezuela that killed more than forty people. Senior officials in President Barack Obama’s administration expressed cautious optimism about the talks, but also condemned the violence [PDF] and refused to take sanctions against Venezuela off the table. After this effort failed, Obama established the Venezuela sanctions program, sanctioned officials involved in human rights abuses, and declared the situation a national security threat to the United States.

2016 Vatican dialogue. The United States expressed support for but did not directly participate in this round that operated under Vatican facilitation with support from UNASUR and former leaders from the Dominican Republic, Panama, and Spain. This effort collapsed after the Maduro regime failed to follow through on a five-point agreement reached with the opposition. This prompted the Vatican to send a letter outlining conditions to resume discussions, which Maduro rejected.

2017–2018 Dominican Republic negotiations. The United States remained silent this round, indicating a lack of support, after Maduro announced elections for 2018 that the opposition pledged to boycott. Despite initial progress on a six-point agenda, the talks collapsed. At the same time, the first Trump administration increased pressure by sanctioning regime officials and expanding the scope of the Venezuela sanctions program.

2019 Oslo-Barbados talks. The United States did not support this round, which took place after Juan Guaidó—then the leader of the opposition-controlled Venezuelan legislature—challenged Maduro’s legitimacy by claiming to be interim president. Norway facilitated the negotiations with the support of an International Contact Group made up of European and Latin American countries. The effort collapsed after the U.S. government announced new comprehensive sanctions against Venezuela, and the Maduro government withdrew from scheduled talks the next day.

According to a 2021 report [PDF] by the U.S. Institute of Peace and the Washington Office on Latin America, both sides perceived the United States as indispensable to the success of the negotiations, but divisions within the U.S. government undercut the opposition’s ability to leverage U.S. sanctions, thereby hurting their credibility at the negotiating table.

Championing dialogue leads to a different result

After maximum pressure sanctions failed to produce leadership change in Venezuela, the opposition and the Maduro regime began a fresh round of talks in Mexico City that started in earnest in 2022. Unlike prior rounds, the United States was committed to these negotiations and held parallel ones with the Maduro regime—though the White House did not confirm this dialogue at the time—which provided the opposition leverage to pressure Maduro into an agreement for elections. The White House went so far as to send a delegation to Caracas in May 2022 and issued sanctions relief to allow Chevron to resume limited operations in Venezuela in support of the resumption of talks that November.

This dialogue—facilitated by Norway, with the support of the Netherlands and Russia as guarantor countries—resulted in the Barbados Agreement on October 17, 2023, which created an electoral roadmap that focused narrowly on conducting a presidential election in 2024. It included the right for both parties to select their presidential candidates, a process for challenging candidate disqualifications, and international observation, among other issues.

One day after the agreement was settled, the United States announced sanctions relief for oil and gas sector operations in Venezuela. The State Department also issued an ultimatum spelling out steps it expected Maduro to take to comply with the terms of the agreement by November 30, 2023, a deadline the regime would not meet.

The opposition held its primary within days of the October agreement. This catapulted Machado onto the international stage as the primary winner and opposition coalition leader who would face Maduro in presidential elections. The turnout of two million geographically diverse voters and overwhelming support for Machado with over 90 percent of the vote defied expectations. Her strong primary performance threatened the Maduro regime, which quickly tried to disqualify the primary results and eventually ratified a fifteen-year disqualification to bar Machado from running for office.

In response to Maduro’s blatant violation of the Barbados Agreement, the United States revoked sanctions relief. These talks, the first with direct involvement from the United States, laid the groundwork for Maduro to agree to an electoral roadmap, which set the terms for an election he lost. The opposition won [PDF] the 2024 election. Despite Maduro’s refusal to accept the results, the Venezuelan people have spoken and they want change.

How to shape future efforts

In prior negotiations regarding Venezuela’s future, the United States has been at most a behind-the-scenes participant, using its leverage to support the opposition and protect its own interests. But the recent U.S. military buildup in the region means that Washington will be a direct participant in future negotiations. There are advantages to direct U.S.-Venezuela negotiations that run parallel to talks between Maduro and the opposition. The reality is that many of the things Maduro likely wants out of negotiations—such as amnesty and guarantees of safety—are things that he will need to negotiate directly with the United States. It can be helpful then for parties to explicitly know where the U.S. government stands on critical issues.

The Trump administration has not communicated the end goal of its Venezuela policy, but it has mentioned certain issues that it will likely want to address in negotiations. These include the return of Venezuelan migrants and access to resources. The administration has already indicated some results on this front, as the United States and Venezuela have continued to coordinate deportation flights. Since the boat strikes began in September, there have been over twenty-five U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) flights from the United States to Venezuela, returning approximately five thousand Venezuelans, according to Human Rights First’s ICE Flight Monitor.

With the United States in a powerful negotiating position, it will benefit the opposition to enlist other countries to support talks and keep pressure on Maduro to commit to a deal and follow through. Machado’s Nobel Peace Prize should serve as a call to action for countries in the region and elsewhere that have supported prior negotiation efforts and will be needed for the next talks.

In any future negotiation, the United States should bear in mind three lessons from the latest round of talks that led to the Barbados Agreement:

- The United States should avoid publicly humiliating Maduro. The United States should issue its demands and ultimatums privately. Private messaging will be more effective than public demands and ultimatums, which are likely to make Maduro dig in for fear of being publicly humiliated. Maduro has stated he wants respect from the United States and to be treated as an equal. The Trump administration’s direct engagements with Maduro have been discreet, which provides Maduro cover for making concessions and gives the U.S. government some room to adapt its approach as the situation changes. Avoiding public humiliation increases the likelihood that Maduro will accept a dignified exit.

- The United States should avoid public all-or-nothing demands. On the one hand, the Barbados Agreement and sanctions relief handed the opposition a strong platform from which to select Machado as its candidate. On the other hand, the strong primary results may have changed the Maduro regime’s calculus about its willingness to follow through on the agreement, putting at risk the electoral roadmap. Future talks should consider how to strategically tie actions and progress to concessions, with the goal of increasing the likelihood of compliance by the Maduro regime and securing U.S. interests.

- The United States should not overvalue sanctions relief. The U.S. government sees sanctions relief as a major concession. But it is possible the Maduro regime, which has survived years of maximum pressure sanctions, does not see it that way. The Maduro regime’s blatant disregard for the Barbados Agreement, which resulted in the revocation of the sanctions relief the United States had issued, indicates that Maduro was only willing to go so far for sanctions relief and that the reimposition of sanctions was not a significant deterrent.

The United States position on past talks between Maduro and the opposition has significantly influenced their outcome. Until now, the United States has been involved behind-the-scenes or remained publicly opposed to these discussions. That can no longer be the case. The U.S. military deployment now put Washington at center stage for any further developments. To advance the cause of democracy in Venezuela, only the United States can de-escalate the situation by bringing Maduro to the table and negotiating a peaceful solution.

This work represents the views and opinions solely of the author. The Council on Foreign Relations is an independent, nonpartisan membership organization, think tank, and publisher, and takes no institutional positions on matters of policy.