On May 29, Colombia will hold its first round of voting to choose the successor to President Ivan Duque, who can’t run for reelection due to term limits. Gustavo Petro, a left-wing senator and former guerrilla fighter, has emerged as the front-runner, and his victory would make him the country’s first leftist president. Many of his proposed policies stand to shake up Colombia’s economic and energy policies, its diplomatic relations, and the implementation of a peace deal that seeks to end decades of internal armed conflict.

Who are the main candidates?

Gustavo Petro. Senator Petro previously fought for the Nineteenth of April Movement (M-19), a guerrilla group, and later became the mayor of Bogota. He led in a late April poll, with more than 40 percent of respondents expressing support, which means he is poised to be one of the two candidates in a run-off election in June. His running mate, Francia Marquez, would become Colombia’s first Black vice president if the pair is elected.

More on:

Petro’s campaign has focused on economic and environmental matters, including a promise to transition away from fossil fuels and toward renewable energy sources such as solar, wind, and hydropower. However, with oil and coal accounting for nearly 60 percent of Colombia’s total exports, his opponents argue this vision isn’t realistic. He has also pledged to combat income inequality [PDF], tax the rich, reform the health-care and pension systems, and weed out corruption.

Federico “Fico” Gutierrez. A civil engineer by training and the former mayor of Medellin, Gutierrez is the leading conservative candidate. He draws support from a coalition of center-right parties that includes former President Alvaro Uribe as well as supporters of President Duque. Best known for his tough-on-crime policies, Gutierrez has promised to restore law and order to a country where social unrest, crime rates, and cartel activity are on the rise.

While he has championed his own anti-poverty policies, including boosting wages and expanding social assistance, he has attacked Petro’s economic plans as being too radical and potentially disastrous. Gutierrez has compared Petro’s candidacy to that of former Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez, who oversaw a socialist overhaul of Venezuela and whose successor, Nicolas Maduro, has systematically dismantled the country’s democracy.

Who else is running?

Other candidates are polling far behind, but there are some notable contenders:

- Ingrid Betancourt is a former senator who was held prisoner by the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) for more than six years. Her campaign focuses on countering corruption, securing reparations for victims of armed conflicts, and bolstering environmental protections.

- Sergio Fajardo is a trained mathematician as well as a former mayor and governor. He has unsuccessfully run for president three times, and his proposals center on improving education and an ambitious tax reform.

- Rodolfo Hernandez is an independent and relatively new to politics, having previously only served as mayor of a departmental capital. Hernandez has gained attention for his unconventional proposals, including calls to legalize cocaine, and his anticorruption stance.

More on:

What will be the biggest challenges for the incoming administration?

Addressing inequality and poverty will rank near the top now that the COVID-19 pandemic has pushed more than 3.6 million Colombians into poverty. Colombia remains one of the most unequal countries in the region, with nearly 40 percent of the population now living below the poverty line and an unemployment rate that has averaged above 11 percent for the past two decades. Inflation reached 5.6 percent in 2021, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine could further complicate matters; the war has hiked up commodity prices, sparking concerns of continued social unrest, even as international sanctions on Russia have increased demand for Colombia’s oil.

Then there is the worsening security situation. The homicide rate rose during the pandemic, and cocaine production has surged to record highs. Fighting has also escalated between guerrilla groups, with splinter factions of the FARC and the National Liberation Army (ELN) competing over drug routes on the Colombia-Venezuela border, while the Gulf Clan launched an armed strike in northern Colombia in protest of its leader’s extradition to the United States.

Meanwhile, Colombia is still a top destination in the region for migrants, especially Venezuelans, nearly two million of whom live in the country. Others from African countries, Cuba, and Haiti cross through Colombia’s Darien Gap on their way to the United States. In turn, the United States continues to expel migrants back to Colombia under Title 42, a controversial public health order. But public opinion on the Colombian government’s open-door policy for Venezuelans is changing: in February, more than half of Colombians surveyed said they favored a more restrictive approach.

How could the result shape the peace accords between the FARC and the Colombian government?

Renewed guerrilla violence has underscored the fragility of peace in Colombia. The peace deal signed in 2016 ended more than five decades of war and granted the FARC political legitimacy in exchange for several concessions, including an immediate cease-fire and disarmament. However, many right-wing politicians oppose the deal over concerns that it offers impunity for crimes committed, and implementation of it has slowed under President Duque.

Both leading candidates say they support the deal, though their proposed approaches to implementation differ. Petro has said he would renew commitment to the deal, as well as look to reach separate agreements with dissident FARC groups and the ELN. Analysts say his dedication to the deal is likely to attract voters, even as his background as a former guerrilla dissuades others. Gutierrez, who has criticized the FARC for failing to uphold their part of the deal, says he would focus on increasing security measures and expanding opportunities for ex-combatants. Regardless of who wins, experts say major aspects of the deal have already fallen behind schedule.

What else is at stake?

A victory for Petro would add Colombia to the growing list of Latin American countries—including Chile and Peru—that have chosen outsider candidates in recent elections. It could also stress Colombia’s close relations with the United States. Some of Petro’s foreign policy views worry Washington, including his proposal to restore diplomatic relations with Venezuela and the possibility that he would cooperate with China and Russia; the White House has already warned of possible Russian interference in the election. He is also an outspoken critic of the U.S.-led war on drugs and hopes to renegotiate the U.S.-Colombia trade agreement, which he argues hurts Colombian farmers and manufacturers.

In contrast, Gutierrez advocates for stronger ties with the United States. His proposed agenda also emphasizes increasing Colombia’s role in regional institutions such as the Organization of American States; bolstering protections for migrants; and creating regionwide, multilateral initiatives that address issues such as drug trafficking and terrorism.

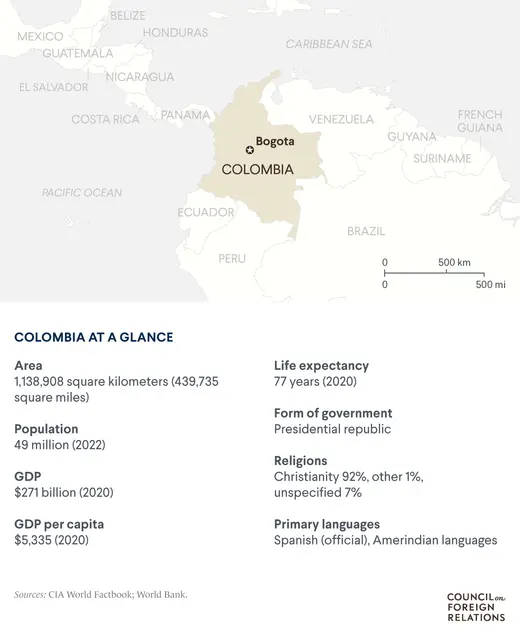

Will Merrow created the map for this In Brief.