The Escalating Ebola Crisis in the DRC

An outbreak in the DRC has spread to neighboring Uganda, and conflict and mistrust of health workers is impeding international efforts to contain the disease.

By experts and staff

- Published

By

- Claire KlobucistaDeputy Editor

An outbreak of the Ebola virus in the Democratic Republic of Congo has spread rapidly in recent months, and health experts say they are losing their grip on the crisis despite a new vaccine.

What’s happening?

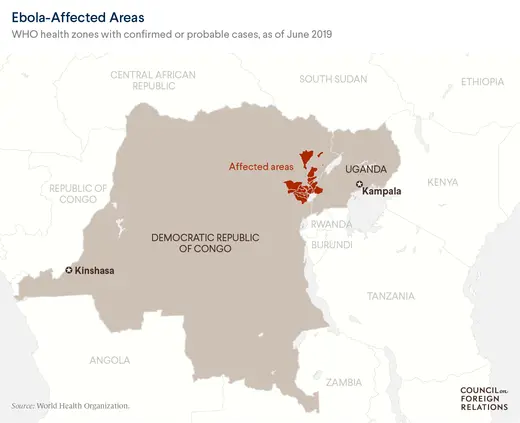

The Congolese government declared the outbreak in August 2018. It’s centered in the northeastern regions of North Kivu and Ituri, which border Rwanda, Uganda, and South Sudan.

The outbreak, already the second largest in history, is growing: cases have doubled over the past three months, surpassing two thousand by early June. Since then, one case has been confirmed outside the DRC, in southwestern Uganda.

So far the outbreak has killed more than 1,300 people. The 2014–2016 West Africa outbreak killed more than eleven thousand people before it was brought under control.

What’s been the response?

Congolese health authorities quickly teamed up with the World Health Organization (WHO) and nongovernmental health organizations, such as Doctors Without Borders and the Red Cross, to try to quell the outbreak. Eight diagnostic labs and fourteen treatment centers are now operating in the country.

The WHO, a UN agency, had come under sharp criticism for its slow response in the West Africa crisis. Many health experts say the DRC outbreak is the first major test of reforms made since then. They include a new contingency fund that has so far provided more than $66 million in emergency financing for this outbreak.

The WHO has led a campaign to vaccinate those most at risk, administering more than a hundred thousand doses of an experimental vaccine first tested during the West Africa crisis. With the rapid rise in cases, it plans to accelerate its efforts. It has also worked with the DRC’s health ministry to launch a trial of other new drugs.

In May the United Nations appointed David Gressly to coordinate the international response and help neighboring countries prepare for possible outbreaks. But some experts have questioned the WHO’s decision to hold off on declaring the outbreak a “public health emergency of international concern.” With its spread to Uganda, the WHO said it will reassess the threat level.

Why is this outbreak so persistent?

The eastern Congo’s instability, poverty, and lack of infrastructure have proved to be towering challenges for those trying to stop the outbreak.

The region’s decades-long conflict continues to play out, with dozens of armed groups jockeying for power and access to the country’s vast mineral wealth. Treatment centers are regularly attacked, and several health workers have been killed and many others evacuated, particularly during the December 2018 presidential election. Aid workers have looked to the country’s nearly twenty thousand UN peacekeepers for protection, but the UN mission lacks support from Kinshasa. Tens of thousands of Congolese fleeing their homes raise the risk that the outbreak will continue to spill across borders.

Also fueling the crisis is misinformation about the disease and mistrust of health workers, rooted in long-standing suspicion of the central government. One 2018 survey found that one-quarter of Congolese respondents don’t believe the Ebola virus is real.

Some Congolese refuse vaccination or treatment, and containment measures, such as taking the highly contagious bodies of Ebola victims from mourning families for burial, often spark anger. The WHO has tried to smooth relations between foreign responders and Congolese by training local residents to be community outreach workers, and President Felix Tshisekedi has made an appeal for trust.

What are the options now?

More help is needed. Aid chiefs have urged the United Nations to help broker a cease-fire. In June the International Rescue Committee called for a “complete reset” on the international response to the crisis. The WHO has only received a little more than one-third of the $87 million it requested for its Ebola response for the first half of 2019, and it says donor countries must step up their contributions.

Health experts warn that time is of the essence. For now the number of cases in the DRC remains far-off from that of the West Africa crisis five years ago, but without quick action this outbreak will continue to grow.

Samuel Parmer contributed to this report.