In Brief

Syria Is Normalizing Relations With Arab Countries. Who Will Benefit?

The Assad regime and Arab capitals will reap the greatest rewards, but ordinary citizens and certain foreign governments involved in Syria’s war have less to gain.

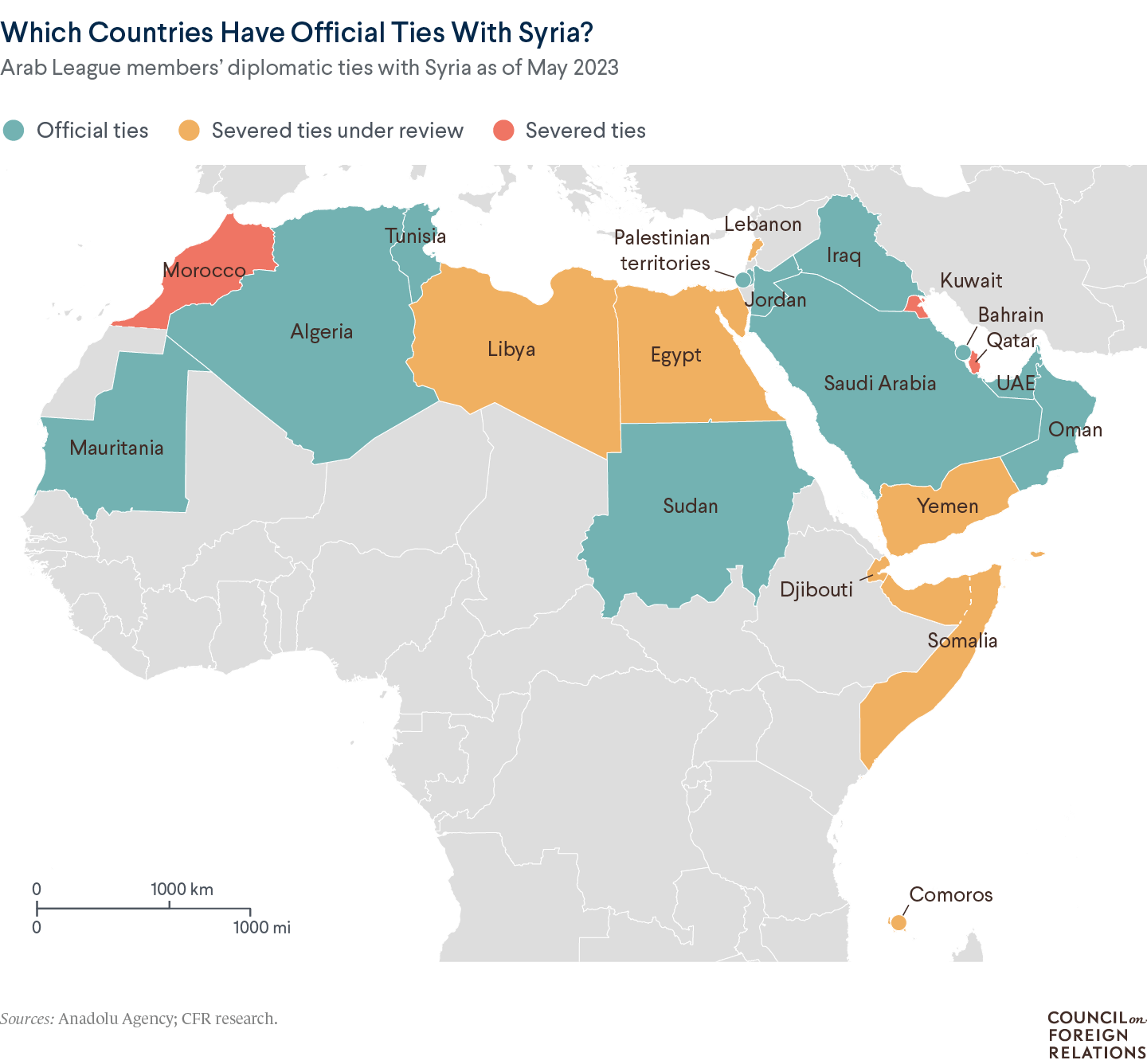

After twelve years of shunning Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, many Arab countries are ready to put the past behind them and normalize relations with his regime. The Arab League underscored this shift by restoring Damascus’s membership in the organization, which had been suspended in 2011 following Assad’s brutal crackdown on anti-regime protesters, and the Syrian leader is now likely to attend the Arab League’s annual summit on May 19.

The rapprochement marks a major diplomatic success for Assad, as well as for his supporters Iran and Russia. It could also deliver significant benefits to his regime and the Arab governments opting for normalization. However, the pivot will likely do little for a Syrian populace that has suffered more than a decade of civil war, state-sanctioned violence, and extremist militancy. And foreign governments that still oppose Assad, including the United States, aren’t welcoming the change.

What’s driving the push for normalization?

More on:

With critical assistance from Iran and Russia, Assad’s forces have regained much rebel-held territory in recent years and now control about two-thirds of Syria. So, although most neighboring Arab governments initially backed and recognized the Syrian opposition, they have come to recognize Assad’s rule as a reality and want to limit further regional destabilization stemming from Syria, experts say.

The twelve-year war has displaced more than half of Syria’s prewar population—over thirteen million people—and killed some three hundred thousand civilians. Many Syrians have fled to nearby countries, such as Lebanon and Turkey, where they now face anti-refugee sentiments. Host governments hope to defuse those tensions by guaranteeing Syrians a safe return home. In addition, they want Assad to rein in illicit flows of captagon, a highly addictive amphetamine that his family has allegedly tapped as the source of more than $50 billion in revenue during the conflict.

The United Arab Emirates took the lead on normalization when it restored ties with Syria in 2018. Countries including Bahrain and Jordan followed shortly after, while Saudi Arabia only signaled interest in rapprochement in the last few months. The February 2023 earthquake in Syria and Turkey seems to have accelerated normalization efforts, giving Syria’s neighbors a chance to reconnect with the regime by delivering humanitarian aid. The recent restoration of diplomatic ties between Saudi Arabia and Iran could also be playing a role. But not every government is on board. Qatar, in particular, continues to denounce Assad and says its position will only be swayed by improvements within Syria.

Does Syria have to make any concessions?

A draft framework for normalization that Jordanian lawmakers are workshopping with other Arab governments asks Damascus to crack down on the captagon trade and guarantee the safe repatriation of Syrian refugees. Saudi Arabia and other Arab powers could also push Syria to decrease its dependence on Iran. Additionally, many of these governments want assurances that the Islamist extremists who control northwestern Syria won’t expand their reach.

What does the Syrian government get out of it?

Most notably, normalization marks a major symbolic victory for Assad, who has been treated as a pariah by most of the world for more than a decade. Currently, the Jordan-led plan isn’t conditioned on political resolutions to the grievances that sparked the war—corruption, poverty, and the political marginalization of the majority Sunni Muslim population by the Alawite Muslim regime, to name a few—or accountability for regime abuses.

More on:

Jordan’s plan outlines other more tangible benefits, such as funding for reconstruction efforts, which could cost as much as $400 billion [PDF]. Arab allies could also urge more countries to mend ties with Syria and reduce sanctions against it, providing a boost for an economy that saw gross domestic product (GDP) fall by half from 2010 to 2020.

Does normalization help the Syrian people?

Syrians are in dire straits: about 25 percent are refugees abroad and around 30 percent are internally displaced. Some 90 percent live under the poverty line. Many observers worry that normalization will offer civilians few immediate benefits. “I don’t see normalization changing the basic situation of ordinary Syrians, at least not in the current stage,” says retired Ambassador William Roebuck, who served as a senior U.S. diplomat in several Arab states, including Syria. “This is mostly statecraft.”

Normalization could eventually help many Syrians gain more freedom of movement and humanitarian aid. Yet, about half the population lives in regions outside the government’s control, which could make it harder for Damascus to steer aid there, Roebuck says. However, those areas do receive aid from international nongovernmental organizations.

It’s unclear what normalization will mean for Syrian refugees, particularly the many dissidents and the large portions of the Sunni Muslim and Christian communities that have fled the country. The Jordan-led plan would urge Damascus to talk to the opposition and allow Arab forces to protect returning refugees, who may fear retaliation or discrimination by the regime. However, some analysts question whether Assad will accept these terms.

What about the non-Arab powers involved in the war?

Washington will likely see normalization as a rebuke of its policy goals, especially because Arab countries appear to be publicly backing an important ally of U.S. rivals Iran and Russia. Meanwhile, both of those countries will see Assad’s rehabilitation as a clear diplomatic win.

The United States is warning against normalization, though U.S. officials have urged Arab countries to “get something for that engagement,” such as a guarantee that Syria will clamp down on the captagon trade. Washington isn’t inclined to alter its own stance on Damascus or redeploy the nine hundred or so troops that it has in Syria to fight Islamist militant groups, Roebuck says.

In neighboring Turkey, which occupies part of northern Syria, the ruling party and opposition are both interested in reestablishing ties with Assad. What that could look like will depend on the results of Turkey’s May 14 presidential election.

Will Merrow and Michael Bricknell created the graphic for this article.

Online Store

Online Store