What Would a No-Deal Brexit Look Like?

The United Kingdom and the European Union have been unable to reach a deal to define their post-Brexit relationship after nearly a year of talks. A severe disruption to trade between them looks increasingly likely.

By experts and staff

- Updated

By

- Andrew ChatzkyWriter/Editor, Economics

- Anshu SiripurapuWriter/Editor, Economics

Britain formally exited the European Union on January 31, but with a transition period lasting through the end of the year, during which it was supposed to work out a trade deal with the bloc. Despite nearly a year of talks, the two sides remain at odds, with little time left to resolve their differences. Barring a last-minute turnaround, the United Kingdom will have to trade with the EU on largely the same terms as third countries, such as Australia and the United States, beginning next year.

Why have they been unable to reach a deal?

The talks hinge on a handful of sticking points—fishing rights in UK waters; so-called level-playing-field provisions, including for “state aid” (subsidies) to British businesses; and the enforcement of an agreement. Although the UK’s ruling Conservative Party has traditionally opposed government intervention in the free market, Prime Minister Boris Johnson wants the freedom to support tech and other companies, says CFR’s Sebastian Mallaby. The EU fears that such aid, along with potentially weaker UK environmental and labor rules, will allow British firms to undercut their EU competitors.

Why does a no-deal Brexit matter?

Economists worry that the British economy would sharply contract. In November 2020, the Bank of England’s governor warned that the long-term economic costs of a no-deal Brexit could be greater than those of the COVID-19 pandemic. There are several specific pain points:

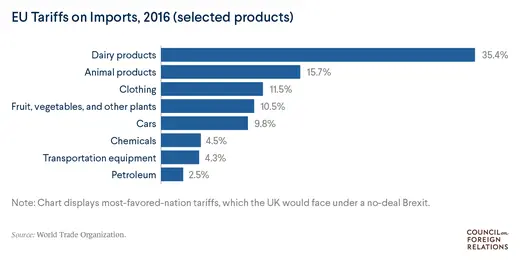

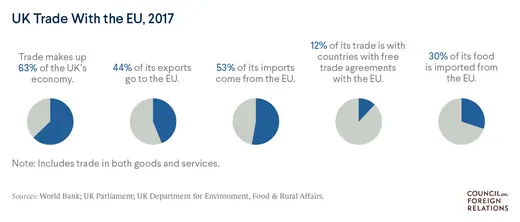

Trade. Trade between the EU and UK totals nearly $900 billion annually. Leaving without a deal means immediately leaving the common market, which guarantees that none of the UK’s trade with EU members faces tariffs or regulatory checks. British exports to the EU would be subject to World Trade Organization (WTO) rules, and face most-favored-nation-level tariffs, which average just under 6 percent but are much higher on certain goods, especially agricultural products.

There would also be new border checks for both exports and imports. This could result in higher prices, border backlogs and delays, and even shortages of staples, such as food and medicine. Companies are scrambling to stockpile goods, causing delays that forced Honda to shut down one of its UK factories. London and Brussels did reach a deal to avoid a so-called hard border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland and instead have customs checks only on goods traversing the Irish Sea.

Investment. Several international firms have shifted their investments from the UK to elsewhere in the EU, fearing that supply chains will be disrupted. Capital invested in the other twenty-seven bloc members grew by 43 percent between 2016 and 2019, while the UK saw a 30 percent drop. London’s role as a world finance leader could also be in jeopardy as financial firms relocate to the continent. Companies have already moved 7,500 employees and more than $1.5 trillion worth of assets out of the UK. The UK has a services trade surplus with the EU, and financial services account for about one-fifth of its services exports.

Migration and security. The status of the millions of EU citizens living legally in the UK, as well as that of the 1.3 million British citizens living in EU countries, has become a major controversy. As of September, the UK had processed nearly four million applications for residency from EU migrants. It has also introduced a new points-based system for granting visas that will prioritize high-skilled and educated workers beginning next year. Some British expats, meanwhile, bemoan the fact that even with legal status in another EU country, they will lose their freedom of movement within the entire bloc. British citizens could also face the EU’s COVID-19 travel ban.

Officials also worry about potential security ramifications; UK police have warned that the loss of access to EU crime databases could undermine their efforts. Proponents of Brexit argue that these fears are overblown.

What’s next?

The EU prepared contingency plans for a no-deal scenario that would keep regulations for air and road travel in place for six months, and extend fishing rights for the same period. The plans would need to be approved by EU member states and the UK.

The UK has aggressively pursued trade deals with other countries, including the United States, its largest trade partner apart from the EU. Although Johnson and U.S. President Donald J. Trump were eager to strike a trade deal, President-Elect Joe Biden could be less inclined to do so. CFR’s Edward Alden says the Biden team should push for a Brexit deal that maintains EU trade rules.

“A clear Brexit outcome that maintains the commitment to high European standards would be a strong signal that a new direction is possible for global trade and capitalism—where governments work cooperatively to make their economies better serve their people,” Alden writes in Foreign Policy.