Red-Teaming the Data Gap

BY

- Jan M. Lodal

- James J. Shinn

Introduction

This paper outlines the information technology requirements of an effective Homeland Defense strategy against further al-Qaeda terror strikes within the United States. It highlights the wide gap between these defensive information technology (IT) requirements and the current fragmented, “stove-piped”, IT capabilities of the Federal agencies involved. The failure of these agencies to share information with each other or to tap into widely available civilian databases leaves the U.S. public dangerously exposed to the next wave of terror incidents.

The Homeland Security IT failure and the dangers it poses to Americans at large can be patched quickly and at very little cost. The paper describes how commercially available techniques from the private sector, including database merge-and-search methods now used in many Internet applications, can be deployed quickly and cheaply to plug the counterterror IT gap, using a fast-turn “Red Team” approach. This is not rocket-science programming: these database sharing and data-mining technologies have been widely deployed by credit agencies and retailers, among others.

Many federal agencies including the Customs Service and the Immigration and Naturalization Service are engaged in frantic efforts to accelerate their large IT systems upgrades in order to cope with the imperatives of national security. The upgrades will take years to specify and then implement, given the scale of these upgrades, the overhang of legacy computer systems, and the straightjacket of federal purchasing procedures. Al-Qaeda is unlikely to stand by until these large scale upgrades are deployed in 5 to 10 years.

It is remarkable that the federal government is spending enormous effort and billions of dollars in the shooting war against terror abroad and in incident-reaction or critical infrastructure protection at home, while expending little effort to put in place a stop-gap shield. The Red Team proposal could start in months, begin providing partial protection against terror strikes within 6 months, use some of the nation’s most sophisticated programming talent, and cost no more than a few million dollars. It is a question of political will and urgency, not a question of technical complexity.

Executive Summary

This paper outlines the information technology requirements of an effective Homeland Defense strategy against further al Q’aeda terror strikes within the United States. It highlights the wide gap between these defensive information technology (IT) requirements and the current fragmented, “stove-piped”, IT capabilities of the Federal agencies involved. The failure of these agencies to share information with each other or to tap into widely available civilian databases leaves the U.S. public dangerously exposed to the next wave of terror incidents.

The Homeland Security IT failure and the dangers it poses to Americans at large can be patched quickly and at very little cost. The paper describes how commercially available techniques from the private sector, including database merge-and-search methods now used in many Internet applications, can be deployed quickly and cheaply to plug the counter-terror IT gap, using a fast-turn “Red Team” approach. This is not rocket-science programming: these database sharing and data-mining technologies have been widely deployed by credit agencies and retailers, among others.

Many federal agencies including the Customs Service and the Immigration and Naturalization Service are engaged in frantic efforts to accelerate their large IT systems upgrades in order to cope with the imperatives of national security. The upgrades will take years to specify and then implement, given the scale of these upgrades, the overhang of legacy computer systems, and the straightjacket of federal purchasing procedures. Al Q’aeda is unlikely to stand by until these large scale upgrades are deployed in 5 to 10 years.

It is remarkable that the federal government is spending enormous effort and billions of dollars in the shooting war against terror abroad and in incident-reaction or critical infrastructure protection at home, while expending little effort to put in place a stop-gap shield. The Red Team proposal could start in months, begin providing partial protection against terror strikes within 6 months, use some of the nation’s most sophisticated programming talent, and cost no more than a few million dollars. It is a question of political will and urgency, not a question of technical complexity.

Analysis

“The Office will...ensure that, to the extent permitted by law, all appropriate and necessary intelligence and law enforcement information relating to homeland security is disseminated to and exchanged among appropriate executive departments and agencies responsible for homeland security and, where appropriate for reasons of homeland security, promote exchange of such information with and among state and local governments and private entities.”

--President’s Executive Order #1, Office of Homeland Security, page 1.

The United States government is groping towards a comprehensive counter-terror strategy that integrates traditional overseas foreign and defense policy with the new challenges of homeland security. Micro-cell terrorists, asymmetric threats, and permeable borders require a novel approach to national security and the creative use of information technology (IT) as a counter-terror weapon.

Some of the IT implications of this strategy can already be perceived. The United States needs a Counter-Terror Information Technology system (CTIT) that combines data from a wide variety of border administration and security agencies, private sector firms in transportation and finance, educational institutions, and foreign sources; in a common format that can be swept by a variety of data-mining technologies; and return useful information on suspicious patterns and behavior in a timely fashion to line agents and law enforcement agencies. The second Homeland Security Presidential guidance document created a Foreign Terrorist Tracking Task Force for just this purpose.

However, the federal government is ill equipped to perform data sharing and filtering tasks among federal agencies in Washington, much less mount an integrated counter-terror information technology campaign in conjunction with state and local governments, the domestic private sector, and allied foreign governments. Moreover, the business-as-usual federal IT contracting approach will not create what the Terrorist Tracking Task Force needs in any reasonable time frame, leaving open a window of vulnerability for which the United States may pay in blood.

Assembling a small “Red Team” to build a fast-turn counter-terror system, using radical programming technologies from the private sector, can mitigate this risk. This approach has served Washington well in the past when faced with security threats. The Red Team can put an interim CTIT in place quickly, fielding an initial system within 6 month. Meanwhile, a parallel “Blue Team” can move forward in the long-term process of re-engineering federal IT systems to provide broad-based counter-terror capabilities in the more usual federal IT timeframe of 5 to 6 years.

The Red Team will use system architectures pioneered in applications for the Internet and on-line transactions processing. For example, sophisticated retailers have made huge investments in order to track consumer behavior across a variety of “touchpoints”, from on-line shopping to in-store visits, using data-mining engines to integrate these touchpoints into a behavioral profile. Credit-card clearinghouses have used similar methods to filter out suspicious behavior patterns and screen for fraud.

These same techniques can be leveraged into powerful, quickly implementable systems that directly address the needs of the CTIT. Many alternative counter-terror applications drawing on these systems can be developed on a decentralized basis by small teams working for the homeland security effort in conjunction with government agencies and civilian firms. Washington can turn the strengths of America’s high tech commercial sector into a “force multiplier” in the battle against terrorism. There are precedents for throwing out the rulebook when the risk is high enough and American technology provides a solution, such as the CIA’s In-Q-Tel venture capital operation that was created in order to jump-start a portfolio of leading-edge technologies with intelligence applications.

The Blue Team will undertake the arduous task of turning around the full panoply of Federal IT projects in order to build a long term, comprehensive, more carefully architected CTIT. The Blue Team will absorb the Red Team’s work, keeping what is useful, discarding those applications of lesser value or robustness, and taking advantage of substantial efforts invested in re-engineering the IT systems and database structures of inputting agencies. The Blue Team’s system will resemble the architecture of the Red Team’s quick-and-dirty CTIT, but scaled up, incorporating more databases and data feeds, and generating alerts in shorter lag times. The Blue Team will use more traditional project management techniques, standards, and the sort of centralized control that characterizes many current federal IT efforts.

The Red Team could begin almost immediately. The most logical place to house this effort is the evolving structure of the Homeland Security Office, or somewhere else close by in the Executive Office of the President. The key organizational issue is providing the political authority to ensure that federal agencies cooperate in providing data to the Red Team and collaborate in testing prototype applications. By the same token, high-level executive authority is crucial to obtaining real-time data feeds from private sector credit card companies, airline and car rental firms, and banks and telecommunications carriers.

What IT System does a Counter-Terror Strategy Require?

The contours of an emerging counter-terror strategy suggest several broad performance parameters for an integrated counter-terror system:

- The al Q’aeda network does not have an explicit political program (at least not yet) that can be negotiated on a state-to-state basis, and its numbers can rise or fall over time, with a large pool of potential recruits. Some adherents are already on security watchlists; others are not, and will not show up on any security radar screen until they strike. Terrorists, dangerous materials, and the illicit “black money” that funds them are widely distributed around the world, as are U.S. citizens, embassies, and military forces. Therefore the Counter-Terror IT system must be able to take in a wide variety of U.S. and foreign government and civilian information on people, materials, and money, and quickly comb these data for suspicious patterns, while developing a variety of rules and algorithms for potential terror events, and effective methods of alerting federal agencies securely and in real-time. The CTIT should be operational with just a few initial data feeds, and become more effective as more information is added incrementally.

- The al Q’aeda network is widely distributed geographically but is relatively small in numbers (at least in the West), organized in even smaller micro-cell teams. To plan, equip, and finance these cells, al Q’aeda leaders and members must cross multiple borders. Watchlists, travel data, communications intercepts, and touchpoints from a wide range of otherwise banal civilian activities, including some from foreign sources, are crucial inputs for a defensive IT system.

- Some microcells are likely already present and “sleeping” within U.S. borders, some with legitimate cover, possibly including U.S. citizens. Others may be smuggled across the border, along with tens of thousands of other illegal immigrants each year. These terrorists will use domestic transportation, communication, and financial networks, swimming as fish in an American sea. They are likely to turn elements of civilian American technology into weapons of terror, the way they used 757 aircraft as cruise missiles. The CTIT must therefore filter a wide-range of otherwise purely domestic civilian activities and transactions in order to pick up indicators of suspicious or threatening behavior.

- The al Q’aeda terrorists and their sympathizers pose a wide range of threats, some entirely “out of the box”, involving chemical, biological, and even nuclear weapons. These networks can strike quickly. As is evident, both the human and economic costs of successful terror operations will be huge. This puts a premium on rapid, forceful response to threats, placing information in the hands of both law enforcement and line agents such as customs inspectors and FBI agents quickly. The CTIT must be available on a 24x7 basis and be smoothly scalable as additional data sources and feeds are added to the system. The system must be able to match watch lists (people, materials, credit cards, travel reservations, hazardous materials trafficking information, flagged telephone numbers) with real time data streams to immediately flag potential alerts.

- The al Q’aeda organization is polyglot and cosmopolitan. This means the CTIT must smoothly integrate foreign language interfaces, not limited to German, French, and Spanish (where several al Q’aeda nodes have been discovered), but also including Arabic and various mid-Eastern and Central Asian dialects. It also requires a common lexicon for deciphering and coding these names, and for dealing with problems such as multiple homonyms and conflicting methods for romanizing Arabic names.

- The micro-cell structure of al Q’aeda is difficult to penetrate except with human intelligence, for which the United States has (currently) little capability. The CTIT will need to quickly format and input human intelligence from foreign allies in a usable fashion, along with a torrent of gossip, half-truths, deliberate disinformation, and other junk data. This requires scrubbing, tagging, and probabilistic interpretation.

- The international coalition against terror in general and al Q’aeda in particular will be flexible, with some states close and trusted, others at arm’s length, others with whom the United States is engaged in active disputes of various kinds, and some who may defect from the coalition or fall themselves. Most coalition partners will want some kind of information in return for cooperating with the U.S. This implies a CTIT with multiple levels of data security that can be rapidly reconfigured and reliably compartmentalized.

- The U.S. and its allies will maintain an open economy and relatively open borders while deterring terror and hunting down suspects. A large volume of people, materials, money and conveyances will continue to cross borders in large volumes. These will have to be tracked between points of origin, transit, entry, and final clearing point. This dictates a CTIT with the ability to sift through mountains of data that is gathered and reported in a variety of differing formats and detail, currently resident in dozens of different databases. It also requires corollary systems for reducing the sheer volume of data to be sifted, by means of special documentation and clearance procedures for cross-border commuters, businessmen, legal migrant workers, and trusted shippers or financial institutions, so that attention can be focused on suspect people and materials instead - in other words, to facilitate an “intelligent profiling” rather than brute force approach to securing U.S. borders.

- Some terrorists are sophisticated, educated people, likely to gain limited access to the same IT systems that are being used to track them. This requires a CTIT with multiple security models and levels of protection, including careful sniffing for unauthorized “fishing” by otherwise authenticated and approved users.

- Finally, even after the Afghan “swamp is drained”, the al Q’aeda network and others will strike at the U.S. heartland in a large scale, deadly fashion. The CTIT must therefore get up and running as soon as possible. Time is of the essence.

The IT Clear and Present Danger

In contrast to this formidable list of CTIT requirements, Federal efforts at sophisticated systems integration have been extremely expensive, slow to implement, and plagued with operational problems. Not only do these IT systems rarely work as intended within a given agency within a reasonable period of time, they rarely talk to other agencies within the Federal government, or with state and local governments, much less communicate with domestic commercial or foreign systems.

For example, consider a merchant ship with a shadowy record of service in the Persian Gulf and the Indian Ocean that is scheduled to arrive in a U.S. port on the same day as a tanker filled with highly volatile material, such as liquid natural gas (LNG). Some crewmembers are on a CIA watch list because of suspected links with Islamic extremist organizations. The shipping agent forwards a manifest whose contents do not square with the homeport or recent ports of call.

Currently, none of these red flags would be reported to more than one U.S. agency. The United States Coast Guard receives some basic data about the merchant ship, and will also know about the tanker, separately. The United States Customs Service (USCS) may know something about the cargo manifest, though often such information is received only when the ship reaches port. The Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) may or may not know anything about the crew, other than their names, depending on what type of visas the sailors are holding and the timeliness with which the shipping agent faxes the crew list. None of the frontline inspectors in any of these agencies are likely to have access to intelligence from the FBI, much less the CIA.

In short, these agencies operate with different systems that don’t talk to each other. There is no integrated information system that could spot a suspect pattern and issue an alert.

These fragmented systems and porous borders are the legacy of an open economy and (in retrospect) naïve assumptions about U.S. immunity to terrorism. In 2000 alone, 489 million people, 127 million vehicles, 11.6 million maritime containers, 11.5 million trucks, 2.2 million railroad cars, 829,000 planes and 211,000 vessels passed through U.S. border inspection systems. The State Department alone issued 100,000 temporary work visas and 280,000 student visas. Between 7 and 8 million illegal immigrants are currently in the United States, half of whom have overstayed tourist or student visas.

The IT systems that are supposed to track these border activities have been patched together over time, hosted on creaky legacy IT systems, and are gradually running out of steam. The systems used by the USCS and the INS, both prone to periodic brownouts, are being gradually replaced by elaborate systems that will take billions of dollars and more than a decade to deploy.

The U.S. Customs Service is in the process of replacing its legacy Automated Customs System (ACS) with a five-year, $1.3 billion Automated Customs Environment (ACE). However, ACE was designed to reduce the paperwork associated with border crossings, not to track malefactors. ACE is only operational at 3 border stations today, will not be fully rolled out until 2004, and does not interface with the FBI’s National Crime Information System (NCIS). Meanwhile, the USCS must spend over $1 billion just to keep ACS running while ACE is developed.

After several false starts, the INS is pursuing a multi-year $1 billion upgrade of its aging array of stand-alone systems, and replacing a number of processes that currently are paper-file based. The new INS system only interfaces with the FBI’s NCIS at two locations. Nor does it interface with the INS border patrol system that uses biometric data to track illegal migrants (mostly along the Mexican border) and also separately from the program that issues digital biometric green cards to resident aliens. The INS Student and Exchange Visitor Information System (SEVIS) system to track foreign students is not operational, despite congressional mandate, and with no link to a database of suspects. The INS mailing of visa approvals to the September 11 hijackers six months after they flew into the World Trade Center tower may be the most embarrassing symptom of the INS’s massive IT failure, but it is only one symptom of a wider and deeper IT problem.

This state of affairs is a legacy of several practices familiar to Washington insiders that hamstring federal procurement in general and federal IT systems acquisition in particular.

- Federal agency IT systems are “stove-piped”, with data kept within the agency and rarely shared. When data is passed on beyond the agency wall, it is scrubbed of much content, and often transmitted in paper format, with long delays. There are several reasons for this, including legal requirements for privacy, widely varying reporting and operational requirements for data, the technical constraints of legacy IT systems, and garden-variety turf protection. The FBI, for example, is concerned with tainting its law enforcement cases with evidence obtained overseas by questionable methods. The CIA is concerned with protecting sources and methods. The U.S. Customs Service is concerned with losing its primacy as the collector of cross-border commercial data, and so on.

- Many agency political appointees relegate IT management to a second or third-tier priority, with little enthusiasm for tackling problem-plagued long-term IT projects which pose short-term political risks and promise only long-term payouts. Moreover, compensation and other administrative obstacles make it difficult to recruit and retain top-flight technical talent within agencies to manage IT acquisition, despite the reforms of the Clinger-Cohen Act.

- There is little inclination to adopt an enterprise system approach by which information systems are designed to support the strategy of the agency’s primary mission or lines of business. Instead, solutions are assembled piecemeal and new functions are piled on incrementally, when a high profile task is perceived by agency heads, mandated by Congress, or in response to some looming legal liability. Large amounts of money are spent on maintaining legacy systems, which reduces the funds and energy available for upgrades and new systems.

- Congressional oversight and the annual federal budget marathon impose administrative overhead and uncertainty on IT systems acquisition. Different Appropriations and Oversight committees have widely varying preferences and prejudices regarding IT expenditure by “their” agencies. Some Members are not above interfering with IT programs in response to district or constituent pressures. Tight budgets and a plethora of Federal rules, combined with constant monitoring by Capitol Hill, not surprising result in risk-avoidance and a reluctance to make innovative IT decisions by agency personnel. Both the agency IT departments and Federal contractors have excellent people and access to the most modern technology: they are constrained more by process than by intent, by lack of leadership more than from lack of talent.

This combination of factors, understandable in a pre-September 11 world, has resulted in a dangerous IT gap in several areas crucial to homeland security. In sum, these federal systems are walled off from each other, and from the private sector, by a combination of legal barriers to data-sharing, bureaucratic inertia, and antiquated technology. This approach will not close the window of America’s vulnerability to al Q’aeda terror for several dangerous years.

Plugging the IT Gap

The combination of the counter-terror strategy requirements and the current state of affairs suggests a two-pronged effort to plug the gap: the Red Team’s short-term effort to build a shallow IT shield to help close the window of vulnerability, and the Blue Team’s long-term effort to re-engineer the inventory of agency IT systems to provide a deep homeland security shield.

The Red Team effort would have the following features:

- It can be created by executive fiat, under the aegis of the Homeland Security Office, with a small kernel staff, a few details from each of the user federal agencies, and a handful of civilian system designers and programmers drawn from Silicon Valley and the “Silicon Alley” Internet world. Most of this latter group would be short-term government employees, others possibly even volunteers. The events of September 11 caused a change in the attitude of quite a few talented people in high technology. Many of these people had hitherto been dubious about the value of government service, wary of Federal infringement on civil liberties, and skeptical about Washington’s ability to build sophisticated IT systems. By the same token, technology vendors such as Compaq, Oracle, or IBM, as well as prominent telecom and financial service providers, would be willing to join in a partnership to defeat terrorism. Many executives and technologists from these firms have already called on officials in Washington to donate their services or their goods. A Red Team effort could attract the top scientific minds at these firms, and ensure that the best technology and data feeds are focused on the CTIT project.

- The Red Team will be relatively cheap, perhaps a few million dollars initially, no more than $25-50 million over its entire life span - a tiny fraction of the Federal government’s annual $25 billion in civilian IT expenditure. The development effort should be kept small, a dozen or so at the beginning, no more than 100 people in later stages, in order to contain the administrative scope and increase the effectiveness of the team. Commercial partners would be willing to defer or donate hardware systems and software tools, which will further cap the budgetary cost.

- The Red Team would adopt a highly decentralized approach, with small teams trying out alternative data-mining tools on different combinations of government and civilian data, gaining quick feedback from different agency users on functionality, and refining these applications. The Team would use rapid “lightweight” programming techniques, sometimes known as extreme programming (or XPR) to field and test a system quickly, and commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) software modules, architectures and tools wherever possible.

- The Red Team would put these early applications in the hands of agency users very quickly, in an iterative process of build/prototype/test/extend, without wasting a lot of time developing formal specifications. In consultation with the user agencies, the Red Team should junk the applications that are dead-ends or useless, while flexibly reforming to work on the ones with promise.

- The Team would build a system that evolves quickly, with five basic modules, one to capture events from the agencies and other touchpoints into messages sent to the CTIT systems, one to process and transform these messages, one to store these events for future analysis, one running data-mining engines, and a fifth to apply rules to the events as they occur and notify appropriate personnel when threatening combinations of events occur.

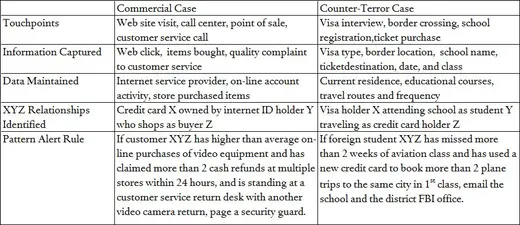

Many applications that integrate reams of data from multiple touchpoints, scan this information on the basis of “suspicion rules”, and generate rapid alerts have been developed and fielded in the commercial world. The following chart shows how the Red Team’s CTIT can be directly translated from existing civilian applications:

The major components of this solution are:

- The Adapter module, which provides a facility for agencies and civilian firms to provide periodic loads of potentially useful database segments, and to forward messages representing other interesting events to the CTIT environment, in a common data format such as XML.

- An Integration Hub using COTS enterprise application integration toolkits (such as SeeBeyond, Tibco, webMethods) and transactional middleware (such as WebLogic Server) to capture events to the CTIT environment. This module provides the ability to log, route, transform messages from the Adapters, and calls on the Interaction Manager to evaluate events in real time and inserts the events into the real time data store.

- The Data Warehouse provides a real time, integrated data store of events from all participating agencies and organizations, built on a 24 x 7 computing platform.

- Analytic Engines permit the CTIT data to be analyzed using data-mining software for the purpose of model building. Models of high-risk scenarios can be constructed of events and their surrounding context. Multiple analytic environments can be maintained to support various organizations that want access to the Data Warehouse.

- The Interaction Manager uses an inference based rules engine to evaluate events as they occur, in order to determine if they are a high risk or of interest to a specific client group. The Interaction Manager executes data-mining modules against context data within the Data Warehouse as well as current event data, while issuing alerts to client groups in the event of suspicious outcomes.

Conclusion

The key point of this paper is the urgency to move quickly to counter an unconventional asymmetric security threat with an equally unconventional defensive weapon -- a sophisticated counter-terror information system. The real challenge for the Red Team is not architecture or technology, however. It is getting political leadership to break the bureaucratic rules and move fast in order to plug the security threat of the IT gap.t