How Do Warren’s and Sanders’s Progressive Foreign Policy Visions Stack Up?

Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders are both progressives, but their foreign policy visions diverge in important ways.

Originally published at World Politics Review

By experts and staff

- Published

By

- Stewart M. PatrickJames H. Binger Senior Fellow in Global Governance and Director of the International Institutions and Global Governance Program

In an article for World Politics Review, CFR James H. Binger Senior Fellow in Global Governance and Director of the International Institutions and Global Governance Program Stewart M. Patrick compares and contrasts the foreign policy visions of Democratic presidential candidates Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders.

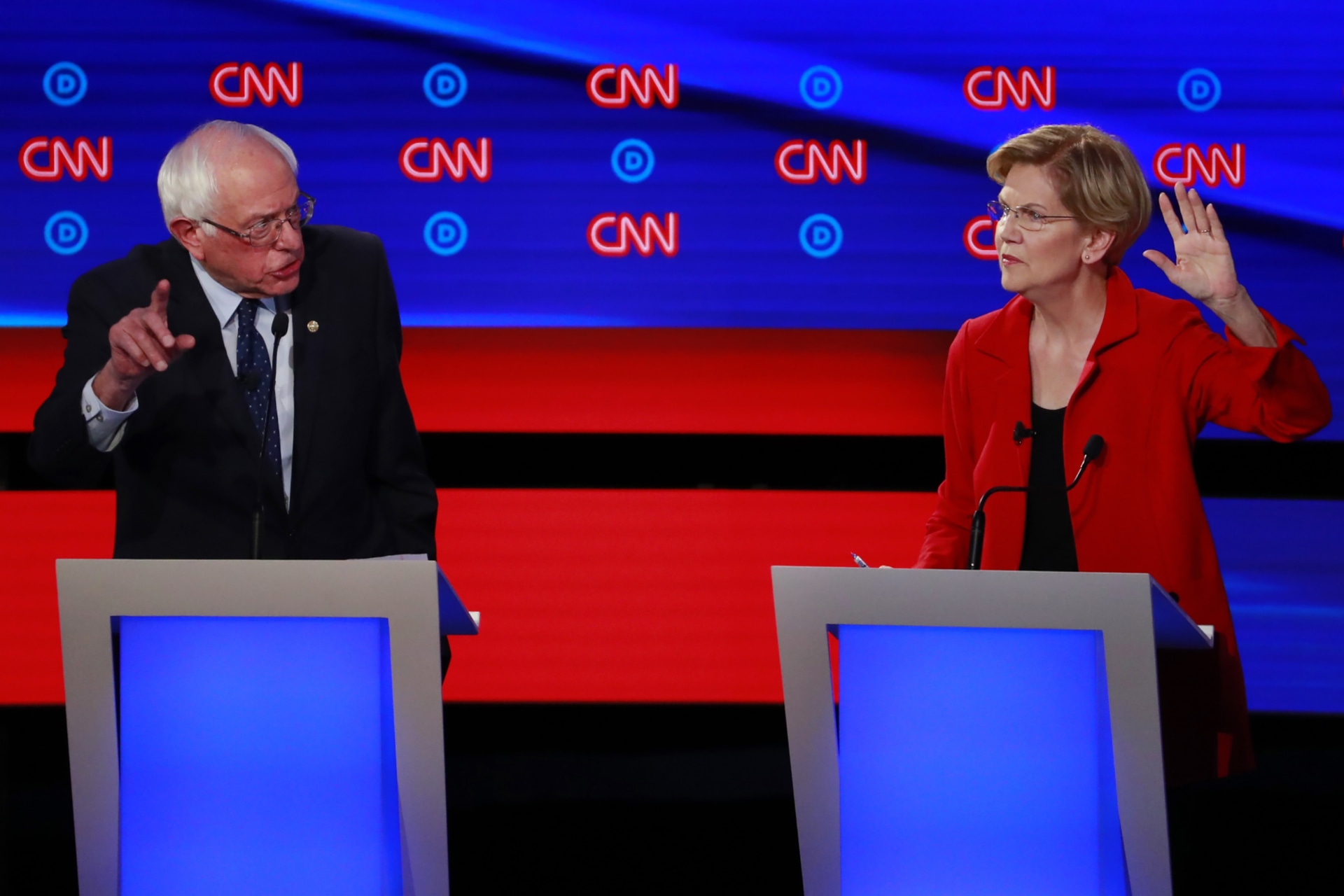

The eventual victor in the chaotic and crowded contest for the Democratic presidential nomination remains to be seen. But one thing seems clear: The political energy in this election cycle is on the left. Elizabeth Warren, the senator from Massachusetts and would-be trust buster, has displaced faltering former Vice President Joe Biden as putative frontrunner. If any evidence of her rise were required, her competitors for the nomination provided it when they trained fire on her in the most recent presidential debate.

But meanwhile, Bernie Sanders, Vermont’s independent socialist senator, is still a fundraising juggernaut, hauling in more than $25 million in the third quarter of the year, largely in the form of small donations from loyal grassroots supporters. Bouncing back from his recent heart attack, Sanders scored a coveted endorsement from freshman congresswoman and left-wing populist darling Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

Given Warren’s sudden surge and Sanders’ staying power, the ultimate Democratic nominee may be someone genuinely new—not a mainstream figure hewing to orthodox, even hawkish, positions, but a left-wing candidate espousing a progressive vision. With that possibility in mind, how do the foreign policy positions of these two leading populists stack up?

Conventional wisdom suggests that Warren and Sanders are aligned on major issues. This is true, broadly speaking. But there is also important daylight between them, not least in their views of America’s global role and the definition of its national interests. Warren, for all her progressivism, is at heart a nationalist, concerned with helping American workers get ahead, while protecting the United States from perceived threats. Sanders, by contrast, is essentially an internationalist, skeptical of claims of American exceptionalism and inspired by socialist ideals to pursue more cosmopolitan goals, including world peace and justice.

Both Warren and Sanders tend to view foreign policy through the lens of economics, as opposed to security. They offer no grand strategy about how to balance geopolitical rivals, limited thoughts about how to deter nuclear proliferation and counter jihadist terrorism, and few insights about the roles that the United Nations, NATO and other multilateral organizations should play in U.S. global engagement.

What they offer instead are positions on distinct global flashpoints. And on these, they are typically aligned. Both advocate rejoining the Iran nuclear deal, removing American troops from Afghanistan, supporting a two-state solution for Israel and Palestine, ending uncritical U.S. support for Saudi Arabia, including for its war in Yemen, and assisting a negotiated settlement in Venezuela. Both favor a posture of U.S. restraint, with less militarism, more diplomacy and renewed attention to human rights. Even so, Sanders stands alone among the frontrunners in condemning the nation’s “endless wars,” which he says have “undermined the United States’ moral authority, caused allies to question our ability to lead, drained our tax coffers and corroded our own democracy.”

On global trade, Warren and Sanders sing largely from the same hymnal. They criticize the globalized economy for rewarding corporations at the expense of workers and single out trade liberalization for hollowing out the American middle class. Both reject the idea of rejoining the Trans-Pacific Partnership, the major Pacific Rim free trade deal that was President Barack Obama’s signature trade policy initiative, and which President Donald Trump quickly exited. They insist that any future trade agreements include adequate protections for labor, human rights and the environment. Each would also crack down on corporate corruption, including loopholes that permit private companies to avoid taxation by hiding profits overseas.

If there is economic daylight between the candidates, it is ideological. Warren has carefully branded herself as a capitalist, while Sanders is a proud democratic socialist. Warren has also adopted the language of nationalism, releasing “A Plan for Economic Patriotism” and calling for “Trade—On Our Terms.” As Politico notes, her plan “is closer to Donald Trump’s agenda than Barack Obama’s.” Sanders frames the reformation of the world economy in sweeping internationalist terms, as a way to bring economic justice to all peoples, regardless of nation.

The candidates take similar positions on climate change. Sanders, who calls global warming an “existential threat,” endorses the Green New Deal, including massive investments in clean energy to decarbonize the U.S. economy by 2050. He pledges to integrate climate considerations into all his foreign and domestic policies. Warren, meanwhile, proposes a $400 billion “Green Apollo” program of research and development, analogous to Washington’s mobilization to put a man on the moon in the 1960s. Both would have the United States rejoin the Paris climate change agreement.

What most sets Warren and Sanders apart is less disagreement over specific policies than divergent assessments of America’s international role and the relationship between U.S. national and global interests. Warren positions herself as both an insider and an outsider, someone prepared to work the system to build consensus. She carries the mantle of reform but reassures the establishment by praising U.S. global leadership and the pursuit of U.S. national interests. She makes it clear that she will place America first.

Sanders offers no such guarantee of continuity, because he sees the ills infecting the United States and the rest of the world as connected. “There is currently a struggle of enormous consequence taking place in the United States and throughout the world,” Sanders declared last year in a speech at Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies. “In it, we see two competing visions. On one hand, we see a growing worldwide movement toward authoritarianism, oligarchy and kleptocracy. On the other side, we see a movement toward strengthening democracy, egalitarianism and economic, social, racial and environmental justice. This struggle,” he argued, “has consequences for the entire future of the planet—economically, socially and environmentally.”

For a democratic socialist, the implications for U.S. foreign policy are clear: America has an international obligation to help ameliorate deprivation, injustice, inequality and tyranny everywhere. As he explained in Foreign Affairs in June, “The time has come to envision a new form of American engagement: one in which the United States leads not in war-making but in bringing people together to find shared solutions to our shared concerns. American power should be measured not by our ability to blow things up, but by our ability to build on our common humanity, harnessing our technology and enormous wealth to create a better life for all people.” In place of nationalism and the national interest, Sanders would help construct a “global community” based on the principle of “human solidarity.”

Sanders’ cosmopolitan vision is a heady brew for radical progressives who regard the sovereign state system as an impediment to global peace, an accomplice to economic injustice, and an obstacle to action on climate change and so many other challenges. The big question, of course, is whether Democrats—much less independents who will help decide the presidency in the general election—are prepared for such a profound break with the past. They might prefer to take their chances with a very different progressive in Warren, who tempers her reformist zeal with familiar elements of continuity.