Space Exploration and U.S. Competitiveness

Published

U.S. space exploration inspired a generation of students and innovators, but NASA’s role has diminished, and the number of global space competitors is growing.

- In 1957, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, the first artificial satellite, sparking a fierce competition with the United States for dominance in space.

- However, U.S. government funding of space exploration has declined in recent decades, while the private sector’s role has grown.

- President Trump boosted NASA’s funding and moved to create a military space force, but the future of U.S. space programs is still uncertain.

What are backgrounders?

Authoritative, accessible, and regularly updated Backgrounders on hundreds of foreign policy topics.

Who Makes them?

The entire CFR editorial team, with regular reviews by fellows and subject matter experts.

Introduction

The 1957 launch of Sputnik and subsequent Russian firsts in space convinced many U.S. policymakers that the country had fallen dangerously behind its Cold War rival. Consecutive U.S. administrations invested in education and scientific research to meet the Soviet challenge. These investments propelled the United States to victory in the so-called space race and planted the seeds for future innovation and economic competitiveness, experts say. Yet, since the 1990s, NASA’s share of federal spending has waned. The U.S. private sector has ramped up investment in space, and in May 2020, astronauts launched from U.S. soil for the first time in nearly a decade on a rocket built by the company SpaceX.

Defining the Mission

The Soviet Union took the world by surprise in October 1957 with the launch of Sputnik, the first artificial satellite. In a matter of months, President Dwight D. Eisenhower and Congress initiated measures to build U.S. scientific and engineering prowess, including the creation of NASA, a civilian space exploration agency.

Presidents have largely determined NASA’s long-term missions. In May 1961—a few weeks after the Soviet Union put the first human, Yuri Gagarin, in space—President John F. Kennedy committed the United States to a lunar landing. He stressed the urgency and value of this mission in a landmark speech at Rice University: “We choose to go the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy but because they are hard; because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills; because that challenge is one that we’re willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one we intend to win.”

After six successful lunar missions, NASA’s manned program pulled back to Earth, while robotic programs such as Voyager and Viking continued to explore the solar system. NASA focused on sending astronauts into low Earth orbit (LEO) with the 1973 launch of Skylab, the first U.S. space station, and the Space Shuttle. The Space Shuttle served NASA for thirty years (1981–2011) and helped build the International Space Station (ISS), an orbiting laboratory that has been continuously occupied by humans since 2000. The agency has also completed a series of unmanned missions to Mars, most recently in February 2021, when it landed the Perseverance rover to search for signs that life previously existed on the planet.

Successive U.S. administrations have set different space goals. The George W. Bush administration pushed for a return to the moon and a trip to Mars, but President Barack Obama favored an asteroid mission. The Obama administration also set a goal of a manned mission to orbit Mars by the mid-2030s, which would require the commitment of subsequent presidents.

President Donald J. Trump’s administration voiced frustration with delays in the development of Orion, a capsule that could one day take astronauts to Mars, and urged a manned return to the moon. At the same time, Trump directed the Department of Defense to create a branch of the military under the aegis of the Air Force that would focus entirely on threats from space, an indication of renewed interest in the field. In February 2020, a proposed organizational structure for the new space force was delivered to Congress. Soon after taking office, President Joe Biden’s administration announced its support of a space force.

Funding NASA

Space exploration is expensive, but it is a relatively minor line item in the U.S. budget.

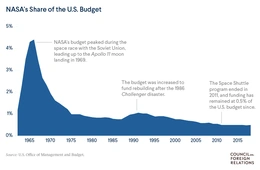

Space exploration is expensive, but it is a relatively minor line item in the U.S. budget. NASA’s spending peaked at almost 4.5 percent of the federal budget in 1966, declined to 1 percent by 1975, and has gradually fallen to about half a percent in recent years. (In comparison, defense spending has hovered around 20 percent of the budget in recent years.) Congress appropriated about $23 billion for NASA in 2021, an increase of roughly 3 percent from the previous year.

Due to the Space Shuttle’s retirement in 2011, NASA did not have the means to send astronauts into space by itself for nearly a decade. U.S. astronauts have had to ride Russia’s Soyuz capsule to the ISS—at a cost of up to $82 million per seat. In 2010, former Apollo astronauts Neil Armstrong and Eugene Cernan warned that U.S. leadership in space exploration could suffer. Such criticisms, as well as Trump’s stated desire to land astronauts on the moon during his tenure, spurred the president to boost his budget requests for the agency.

Commercializing Space

Historically, 85 to 90 percent of NASA’s budget went to private contractors—largely to design and manufacture rockets and spacecraft—while NASA maintained close oversight and operated the equipment. But now NASA often privatizes operations as well. Advocates of space commercialization believe private firms such as SpaceX and Orbital Sciences, both of which won contracts to ferry ISS cargo, can provide routine LEO access at a lower cost. They say NASA could then focus more on missions that push scientific and exploration frontiers. Some go further to suggest that NASA become more like the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency or the National Science Foundation by setting objectives, such as capturing an asteroid, and then giving grants to private firms. But critics of privatization argue that development grants and limited competition will yield scant savings. Astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson believes that while private enterprises can handle routine space flight, they are unable to bear the large and unknown risks of advancing the space frontier.

In May 2020, SpaceX became the first private company to successfully ferry two NASA astronauts to the ISS, using its Falcon 9 rocket and attached Crew Dragon capsule. President Trump said the launch “makes clear the commercial space industry is the future.” The astronauts safely returned to Earth in August, and in November, NASA certified SpaceX to begin routine missions. The first of these was carried out that same month, sending four astronauts—three American and one Japanese—to the ISS. Additionally, SpaceX has announced that it plans to send three space tourists to the ISS in late 2021.

NASA is also collaborating with the private sector for its Artemis program, which aims to put astronauts, including the first woman, on the moon by 2024. In April 2020, NASA announced that the human landers for the program would be developed by SpaceX; Blue Origin, owned by Jeff Bezos, founder and chief executive of Amazon; and the Alabama-based company Dynetics. The Biden administration has pledged its continued support for Artemis.

Some entrepreneurs see a commercial future in space beyond NASA contracts and satellite launches. U.S.-based Space Adventures offers customers the opportunity to orbit Earth and experience the views and weightlessness of space travel. Other firms have pursued asteroid mining, which supporters believe could supply a new abundance of precious metals and rare earth elements. Bezos has said he plans to “build a road to space” so that humans will one day be able to sustain colonies beyond Earth. Fellow billionaire Richard Branson founded the spaceflight firm Virgin Galactic, hoping to become the industry leader in a future space tourism sector.

Launching STEM Careers and Innovations

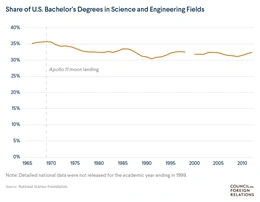

The space race of the 1960s and 1970s captured the American public’s imagination like few other human endeavors. A 2009 study in the journal Nature found that the Apollo program had inspired half of scientists surveyed, and almost 90 percent believed that manned space exploration inspired younger generations to study science. Some evidence supports this. According to the National Science Foundation, the percentage of graduates holding bachelor’s degrees in science and engineering fields peaked in the late 1960s, around the time of the moon landing, but then declined slowly for several decades before recent administrations began to reemphasize [PDF] the importance of funding science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) education.

Space exploration can also foster innovation, pushing the limits of technology and requiring the collaboration of some of the brightest people across multiple disciplines. As Jim Bell, president of the Planetary Society, a nonprofit group dedicated to space exploration advocacy and education, told CFR, “When you’re embarking on an enterprise that is the hardest thing to do, it often attracts the best people who are intrigued by very difficult problems and want to have a sense in purpose in applying their knowledge to something big.”

Since 1976, technologies originally developed for space exploration have led to more than two thousand spinoffs when they were transferred to the private sector. Some are obvious, such as communications satellites, but other transfers are less well known. Many medical advances are derived from space technologies, such as refinements in artificial hearts, improved mammograms, and laser eye surgery. Space exploration drove the development of new materials and industrial techniques, including thermoelectric coolers for microchips; high-temperature lubricants; and a means for mass-producing carbon nanotubes, a material with significant engineering potential. Household products such as memory-foam mattresses, Bluetooth headphones, programmable ovens, vacuums, and ski apparel all trace their origins to NASA.

International Competition and Cooperation

Only the United States has sent people beyond low Earth orbit, but experts say U.S. preeminence in space could be challenged. China became the third nation to independently launch a human into orbit in 2003 and its capabilities have since grown. The People’s Liberation Army is seen as a driver of the Chinese space program, the ambitions of which include sending people to the moon and building a space station. Meanwhile, India launched its first unmanned mission to Mars in late 2013, and its probe entered Mars’s orbit in September 2014. The Indian Space Research Organisation has since reached an agreement with NASA on subsequent explorations of Mars. China and the United Arab Emirates successfully sent spacecraft to orbit Mars in February 2021, the same month that NASA landed its rover there; the Chinese mission includes its own robotic explorer.

Only the United States has sent people beyond low Earth orbit, but experts say U.S. preeminence in space could be challenged.

Another international mission, the landing of a European Space Agency probe on a comet, attracted widespread interest in November 2014. Though the probe was unable to anchor properly due to a landing mishap, it was still able to send a large amount of valuable data to scientists. SpaceIL, an Israeli organization, launched a moon lander in early 2019 that ultimately crashed into the moon. Nevertheless, the attempt marked the first privately funded moon landing and made Israel the fourth country to attempt a soft moon landing. India became the fifth such country in September 2019, but it too failed when its lander appeared to crash into the moon.

Space can also inspire international cooperation. In 1963, during what would be his final speech before the United Nations, President Kennedy asked, “Why should the United States and the Soviet Union, in preparing for such expeditions, become involved in immense duplications of research, construction, and expenditure?”

Kennedy’s vision eventually materialized with the 1975 Apollo-Soyuz Test Project, in which U.S. and Russian spacecraft docked for the first time. Today, the United States is the ISS’s managing partner, leading fourteen nations in perhaps humanity’s most expensive project. The space agencies of Europe, Russia, and Japan were also important partners on robotic missions such as the Mars rovers Spirit and Opportunity. The ISS will likely deorbit in the 2020s, but many say deeper space missions will need to be international ventures.

In May 2020, NASA announced the framework for the Artemis Accords, a series of bilateral agreements with other space agencies that want to participate in the Artemis program. CFR’s David P. Fidler praised the accords, writing that they “embrace rules and principles developed through multilateralism rather than a scofflaw version of American unilateralism.”

The Space Force and Uncertainty Ahead

Space policy experts agree that NASA faces considerable challenges, including new budget pressures, aging infrastructure, the rise of competing spacefaring nations, and the lack of a strong national vision for human spaceflight. An independent assessment by the National Research Council in 2012 noted that a crewed mission to Mars “has never received sufficient funding to advance beyond the rhetoric stage.”

The Trump administration’s push to create a space force within the military could be a sign that an era of cooperation in space is ending. In response to Trump’s order, Daryl G. Kimball of the Arms Control Association said, “At worst, it is the first step in an accelerated competition between the U.S., China and Russia in the space realm that is going to be more difficult to avert without direct talks about responsible rules of the road.” CFR’s Stewart M. Patrick agrees that “the stage could be set for a Cold War–style space race that overwhelms any multilateral cooperation.”

At the same time, policymakers face a growing number of issues around NASA’s present-day purpose and methods. These include how the agency should balance various goals, such as driving scientific discovery, enhancing national security, and developing innovations with commercial benefits; how large a role the private sector should play; and to what extent NASA can be a vehicle for international cooperation and diplomacy.

Despite these questions, many experts have advocated sustaining U.S. leadership in space. “I’m convinced that in this century the nations that lead in the world are going to be those that create new knowledge. And one of the places where you have a huge opportunity to create new knowledge will be exploration of the universe, exploration of the solar system, and the building of technology that allows you to do that,” said former congressman and aerospace expert Robert Walker at a CFR meeting on space policy in 2013.

Recommended Resources

Watch the Perseverance rover land on Mars and listen to audio it transmitted from the planet.

Rajeswari Pillai Rajagopalan explains the need for a new outer space treaty in this Global Governance Working Paper.

The Washington Post looks at all the private companies and entrepreneurs involved in space exploration.

Watch full episodes of the History Channel’s The Universe series, an educational program exploring the mysteries of the cosmos.t

Colophon

Staff Writers

- Andrew Chatzky

- Anshu Siripurapu

- Steven J. Markovich

Additional Reporting

Header image by Joe Skipper/Reuters.