So, Is China Pegging to the Dollar or to a Basket?

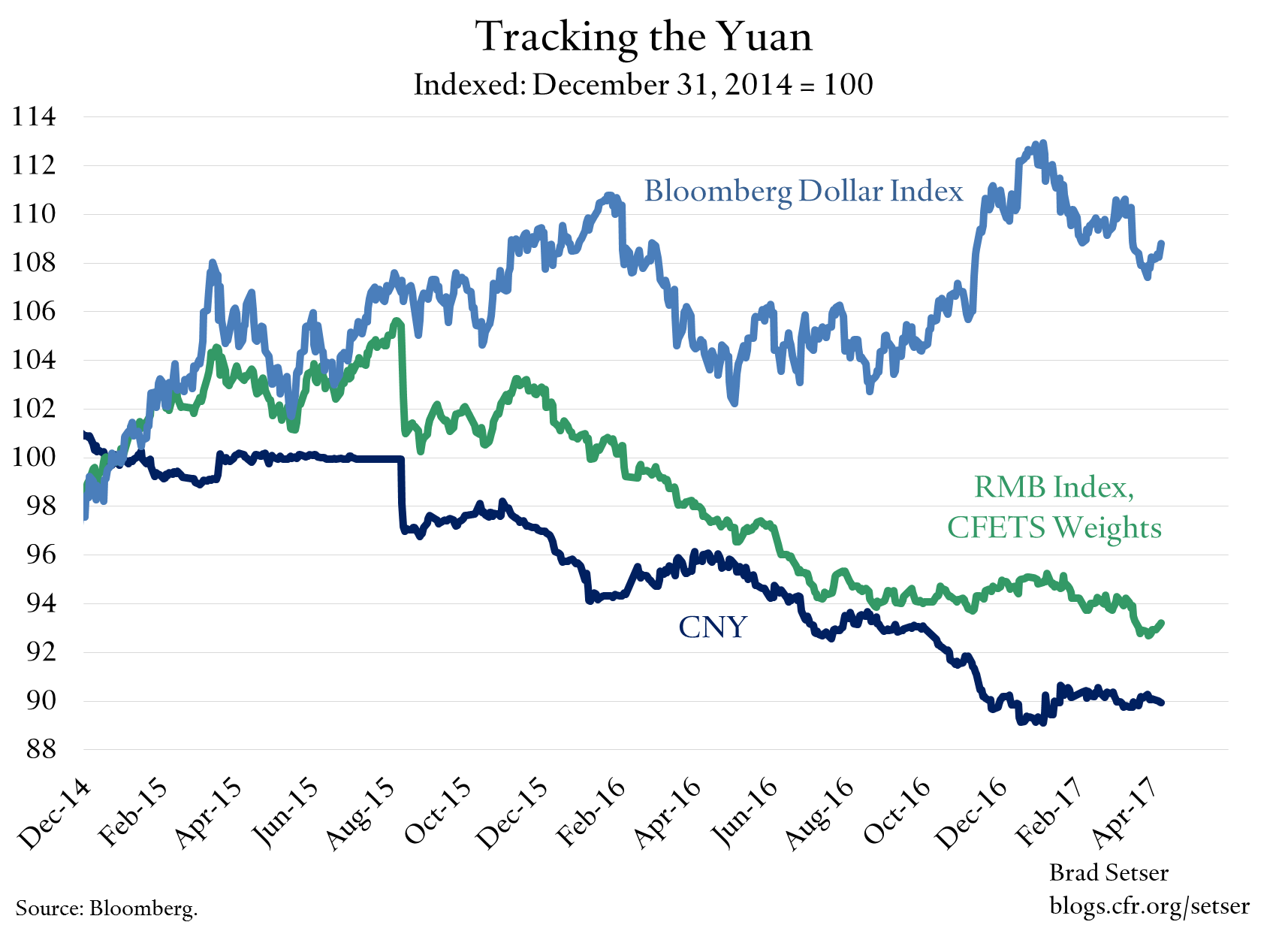

Does China manage its currency against the dollar, against a basket, or to whatever is most convenient at any given point time? Cynics have argued that China seems to peg to the dollar when the dollar is going down and the basket when the dollar is going up.

The yuan’s moves in March at least raise the question again, even if the signal is relatively weak.

The yuan has hewed fairly closely to the dollar over the last few weeks. And in March that meant some modest depreciation against the basket (though the depreciation against the basket was partially reversed in the first week of April when the dollar rose). In other words, had China managed more against a basket, the yuan should have appreciated a bit more against the dollar than it did.

Managing the yuan against the dollar is in some ways less risky than managing against a basket, as Chinese residents still seem to focus on the yuan’s value against the dollar. Stability against the dollar so far this year—and tighter controls— has contributed to the relative stability in China’s headline reserves. It is likely that China is no longer selling all that much foreign exchange in the market, though we still need the settlement data and the PBOC balance sheet data to have a clear picture for March.

But I still worry a bit. The risk all along has been that China’s new policy of managing its currency against the basket was masking a policy of managing its currency to depreciate against the basket.

From mid-2015 to mid-2016 China used periods of dollar weakness to depreciate against a basket—and thus created the perception of a one-way bet. China needs to make sure such expectations do not reappear, whether by really managing against the dollar—even if that means following the dollar up—or really managing against a basket.

One last point: it would be a shame if discussions around currency are defined entirely by the question of “manipulation or not.” It would be a stretch to argue that China is manipulating (there are lots of potential ways to define manipulation, but recently it has been defined as buying foreign exchange in the market to hold your currency down and support a large current account surplus -- and China clearly has selling foreign exchange in the market to support its currency over the past year, and its stimulus has brought its current account surplus down).

But the way China manages its currency matters—to the U.S. and to the world. The value of the yuan, more than any other single factor, determines whether it makes sense to locate production in China for U.S. sales, or locate production in the U.S. for sales to China. Of course sectoral barriers matter. But in theory, restrictive Chinese policies in one sector should be offset in part by moves in the currency—fewer Chinese imports should mean a stronger currency, and fewer exports. The sectoral barriers thus matter for particular firms, but the exchange rate matters for the broader economy.*

That is why I think China’s currency management needs to remain on the bilateral and multilateral agenda and why I disagree with those who argue that other issues (notably the ability of U.S. firms to invest more freely in China) matters more to the U.S. economy than the level of the exchange rate.

* As an example, total U.S. beef exports are around $6 billion, with $1.5 billion in exports to Japan and almost $700 million to Hong Kong (call me cynical, but I would not be surprised if some U.S. beef already enters the Chinese market). Even if China started to buy two times as much beef as Japan ($3 billion), it wouldn’t really change the overall trade balance by much. U.S. pork exports to China have gotten a lot of attention, but total pork exports to China and Hong Kong still total only around $1 billion a year (total pork exports to the world are $6 billion). Changing the overall trade balance really requires changing the incentives facing a broad set of industries - something that is most easily achieved through a change in the exchange rate.