Human Rights

Refugees and Displaced Persons

-

Responding to the Rise of Global MigrationFASKIANOS: Thank you and welcome everybody. I'm Irina Faskianos, vice president of the National Program and Outreach at the Council on Foreign Relations. As a reminder, today's session is on the record. I am delighted to be moderating today's conversation on the rise of global migration and to introduce a wonderful panel. Nazanin Ash is vice president for public policy and advocacy at the International Rescue Committee and a visiting policy fellow at the Center for Global Development. Previously, she served as deputy assistant secretary in the Bureau of Near Eastern Affairs at the State Department, and as a principal advisor and chief of staff to the first director of U.S. foreign assistance and administrator at USAID. Elizabeth Ferris is a research professor at Georgetown University's Institute for the Study of International Migration and a nonresident senior fellow in foreign policy at the Brookings Institution. She spent twenty years working in the field of international humanitarian response, most recently in Geneva, Switzerland, and at the World Council of Churches. And Krish O'Mara Vignarajah is president and CEO of Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service. She previously served in the Obama White House as policy director for First Lady Michelle Obama. She's also served as senior advisor under Secretaries of State Hillary Clinton and John Kerry at the State Department where she coordinated development and implementation of programs including those concerning refugees and migration and engagement with religious communities. So thank you all very much for being with us. I thought we would first go to Nazanin to set the table and to provide an overview of global migration trends, where people are migrating from, where they're migrating to, and why are they fleeing? ASH: Thanks so much, Irina. Thanks so much for your introduction. Thanks so much for hosting us today. I'm so pleased and excited to be here with you and with my distinguished colleagues. It's going to be a great and necessary discussion. You get to convene this discussion at a moment of unprecedented global migration. There are over eighty million people displaced worldwide today. That's the highest number ever recorded. Thirty million of those are refugees, and importantly, that number is double what it was just a decade ago. So if you consider many decades, that it took to get tothe forty-one million globally displaced just a decade ago, and then the doubling in the last decade, the right question to ask is, “Why?” You know, why these ever-increasing numbers of those who are displaced. And while there are a number of factors that contribute to that displacement, including climate change, conflict remains the number one driver of displacement today accounting for 80 percent of those displaced. If you assess that same figure a little over a decade ago, you would have found that 80 percent were displaced as a function of natural disasters. But today, it's really conflict that's driving displacement. That tracks really closely with trends in conflict. The number of conflicts globally is 60 percent higher today than it was a decade ago. And civilian deaths account for 75 to 95 percent of all conflict-related deaths. So when we ask the question about “why” this global displacement, I think it's critically important to center on the fact that these are civilians fleeing violence and oppression, rising violence and oppression. Almost 70 percent of all refugees come from just five countries—Syria, Venezuela, Afghanistan, South Sudan, and Myanmar. These are all countries that we know well for long-standing and deepening conflict, and for social and political oppression. So again, it’s critical to remember the reasons why the numbers are rising as they are. People are fleeing for their lives and they're fleeing for safety. The other trend that's really different in the context of global displacement today is its protracted nature. And again, that tracks closely with conflict as the driving trend. Today's conflicts are most often civil wars with multiple actors; they're very difficult to resolve. Conflicts on average today last thirty-seven years, and they're well beyond the reach of some of our typical tools for addressing conflict. So unsurprisingly, displacement is increasingly protracted. And in a context where just 1 percent of refugees globally have the opportunity to resettle permanently to a third country and less than 3 percent on average over the last decade are able to go home, you have almost 90 percent of the world's refugees hosted in low- and middle-income countries, neighboring countries in conflict, and struggling to respond to the development needs of their citizens and also hosting large populations of displaced people in great need of safety and protection for long periods of time. FASKIANOS: Thank you very much for that. I'm going to go next to you, Beth, to talk about the Biden administration's immigration policies. We've seen that this has been already just, well, a bit over a hundred days in, this has become a flashpoint for the administration on the border. But it's much broader than that. So if you can talk about what you see and how it compares to prior administrations that would be great. FERRIS: Great, thanks a lot. And thanks for an opportunity to talk about this issue. Maybe to draw the link with your title, I mean, faith-based communities have really been in the league for advocating for changes in U.S. policy for immigration, both refugees and immigrants, and had very high hopes when Biden was elected that he would reverse some of Trump's anti-immigrant policies in a range of areas. And indeed, on his very first day in office, he introduced legislation on a comprehensive immigration reform bill, which right now people don't think has a great chance of being passed, but certainly indicating his commitment. He's issued a number of executive orders according to the Migration Policy Institute as of a couple of weeks ago. He's done ninety-four executive actions on immigration, over half of which have been to overturn some of the policies that were enacted under the previous administration. And the focus seems to be primarily on the border where I'm sure you've all seen that, in March of this year, the highest number of apprehensions on the border and nineteen thousand unaccompanied children. The crisis on the border is a humanitarian crisis—how to meet the needs of all of these people. The Biden administration has overturned some of the worst aspects of Trump's policy, particularly the Migration Protection Protocol so that people are no longer being sent back to Mexico to wait to ask for asylum. And indeed, some of those who've been waiting for a couple of years are being allowed to enter the United States and ask for legal protection. But at the same time, some policies remain, this so-called Title 42, which essentially closes the border because of COVID and health concerns to all but essential travel. Most countries in the world have closed their border to most travelers. And yet, certainly in Europe, there's an exception made for people who are fleeing persecution to be able to ask for asylum. That hasn't happened yet on Biden's watch. Another major area is that of refugee resettlement. The numbers of refugees resettled in the U.S. plummeted under the Trump administration. And Biden campaigned on pledge to increase those numbers from a paltry fifteen thousand to one hundred twenty-five thousand. Refugee advocates were really disappointed when, for a couple of months, there was no action. This is what Biden said he was going to do, but he didn't sign the presidential determination until two months later. And at that time, he kept with the Trump number of fifteen thousand, largely due to concerted action by advocates, members of Congress, members of local communities who recognized that refugees are a benefit to our country. That was reversed, and we now have a ceiling of sixty-two thousand five hundred by the end of October. But as of right now, less than twenty-five hundred have arrived, partly because of COVID. People can't travel as easily to do the interviews or prepare people and partly because of the effects of the Trump administration in terms of our domestic capacity to have offices with interpreters, for example, to welcome newcomers. It's going to be a while before that program has been built up. So a lot of attention is focusing on those two issues. They're two very different programs. But in the public's mind, they're linked. They're all refugees. And I think that one of the challenges for faith-based communities and others is to educate the public in terms of the differences between some of these categories and processes. And I'll just add, I could talk on and on about this, but there also have been a number of other actions that haven't received as much attention but, an effort on the DACA, seven hundred thousand people, young people, mostly young people now in the United States. Biden has offered temporary protected status to Venezuelans, which is great, and to people from Myanmar, which is great, and really, really cutting down on enforcement action. So people are being deported now for their threat to national security or public safety, really trying not to separate families so much. A change in terminology—the Biden administration said they will no longer use the term “illegal alien,” and will talk about undocumented non-citizens. That's a rhetorical change. But I think in the eyes of many, it represents something far more. So there have been a lot of changes that have occurred, but expectations are very high. Under the Biden administration, the United States will affirm its identity as a nation of immigrants and come up with ways so welcome people more effectively. FASKIANOS: And just to follow up, do you think that changing the name will help reduce the political debate about—it becomes less, it might make it a little bit less partisan if— FERRIS: That's, you know, you change the terminology. But habits die hard. I heard this morning from people on the border that many of our border patrol are still using the term “illegal alien,” so it has to be more than symbolic but somehow to, again, to affirm that immigrants are bringing many talents and resources. They're not just by any means rapists and murderers and drug dealers, but they're honest, for the most part, decent, hard-working people who are fleeing violence, persecution. This country has a rich tradition of welcoming people that nobody else wants. Our country is better for it, so I think we need to reaffirm those values and not be shy about it. FASKIANOS: Thank you. And I'm going to go next to Krish to talk about faith-based immigration interventions and how faith communities can mobilize to assist refugees and immigrants, what you're doing with your organization and the agency that you have. VIGNARAJAH: Wonderful. Well, thanks so much for having me. It's really delightful to speak, especially alongside Elizabeth and Nazanin. Having been a CFR term member, it feels wonderful to convene. Once again, obviously, I have especially fond memories of being able to sit around those large circular tables, but for the moment I suppose this will do. So I am the president and CEO of Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service, and we are the largest faith-based nonprofit dedicated to refugees and immigrants. And I will tell you that it is not just the Lutherans that have a particular focus on working with refugees. The vast majority of the nine refugee resettlement agencies are faith-based. And I think that for so many faiths welcoming the stranger is literally a part of scripture. So I think that I can certainly speak on behalf of myself and some of the faith-based organizations where for so many faith organization congregations it is essential, and they have been central to the broader process of resettling families into new homes and cities and towns across the country. Communities of faith have been critical to our organization, whether it's sharing information, advocating on behalf of refugees, and conducting programs to support our clients. And so I'll try to kind of briefly summarize some of the incredible and substantive ways in which faith communities assist refugees and immigrants. So, first in terms of advocacy, we have certainly seen that faith communities can uniquely navigate the intensified politicization of refugee and immigration issues. Obviously, it was just kind of talked about some of the politics that play into this. And I know, Irina, you just asked the question about how do changes in terminology even affect policy, and they can be significant. We'd like to believe that moving away from the dehumanization of immigrants by using terminology like “aliens” can recognize that tenant of human dignity, which is that whether we're talking about unaccompanied children or families, that what we are talking about are people and family units, that I'd like to believe that as a core American value treating a child with dignity and respect is something that whatever side of the aisle you sit on that you can agree that kids don't belong in cages. So what we have found is that faith leaders are key participants in our work of advocacy to try to move this issue area out of the political arena. So in fact, we have an upcoming World Refugee Day that a number of organizations are a part of. We're doing it virtually, not surprisingly, this year on June 22, and faith leaders will be a key part of that advocacy. We also do action alerts with our congregations and other faith communities in order to kind of pinpoint specific pieces of legislation and to engage them. In terms of programming, volunteering is such a critical part of our work that relies on those of faith communities. Much of our work is very time intensive so volunteers can provide transportation for refugee and immigrant families. They can serve as teachers of English for those who English is a second language. They can help us set up apartments for refugee families as they're first arriving at the airport and we're, identifying a modest apartment for them to move into. I can tell you even from my personal experience, I wasn't technically a refugee when my family came to this country, but we fled Sri Lanka when it was on the brink of civil war. Coming from a tropical island and, you know, I was nine months old at that time, but my parents recall how they'd never seen a winter. And so having churches and temples who literally equipped us with winter coats, it was those faith communities that really stood up and stood by us as we were foreigners on American soil. We find that our faith communities are actively engaged in programs where we rate immigrants in detention to let them know that they're not alone or even to open up their homes and hearts and serve as foster care parents. We run programs, including transitional foster care, for unaccompanied children so as we're trying to reunite them with their sponsor, it's incredibly important for us rather than warehousing these children in large facilities that we can provide them a safe, small, family centric home. And so faith communities are very actively involved in that. And then I think the final piece I'll end with is just talking about some of our annual programs are really focused knowing that this is an incredibly engaged community. So just to give you a couple programs, we have one program called Stand Up, Speak Up!, which is an interfaith vigil. We have a program called Gather, which equips congregations and communities to learn about a region or country. As Nazanin mentioned, we do see concentrations of refugees and other immigrants coming from specific countries. So explaining who these families are, why they're fleeing the desperate circumstances and seeking refugee protection in the United States, it's been important for us to launch programs like this, or EMMAUS, which is a three-part congregational discernment program, to allow congregations to work alongside refugees. And then the final program, just because it is one of my favorites, I'll note, is Hope for the Holidays. This is a program and we find our faith communities incredibly excited each year. It's how we send cards to families in detention. So we have found that even during the pandemic we were able to send gifts to children who found themselves in detention during the Christmas holiday. We sent more than sixteen thousand cards to families and individuals, and many thanks to faith-based communities as well. FASKIANOS: And just to follow up, Krish, how have you pivoted during the past year of the pandemic and lockdown? I mean, how has that changed your work and has the Zoom format enabled you to do more or less? VIGNARAJAH: Yes, it's a great question because it has actually been incredibly inspiring to see the creativity and the flexibility with which our staff and our affiliates all across the country have mobilized. So rather than doing in-person check-ins in a living room, those who transition to porch check-ins, I think that there's actually some real room to grow and adapt, frankly, by being forced into more of a virtual environment. I think there's ways in which some of our mentoring—when I mentioned kind of English as a second language, that training—I believe that we could actually engage individuals all across the country who may not be in an urban center or close to one of our offices who, thanks to a computer and this kind of format, could engage. So I think that is where it's been really exciting to see the options opened up by these possibilities. We've also mobilized knowing that so many of the clients that we serve have been on the frontlines. They've served as essential workers. They've been in our fields literally providing food on our tables. They've been at grocery stores.I think one of the things that we've also seen unfortunately is our workforce development programs overnight have become unemployment offices. So we launched a fund called Neighbors in Need, which was an emergency fund, in order to help so many of our clients who worked in hospitality, the service sector, tourism, who lost their jobs. It's been incredibly exciting to see how many people who may have been also financially affected. They got the $1,000 stimulus check, and they said, “You know what, I could use this but honestly these families could use it more,” and sent that donation to us. So it's actually been really an incredible time to see how Americans have continued to show that we are a welcoming nation. FASKIANOS: That's very inspiring. Nazanin, I want to go back to you to talk about what you see as the responsibilities of wealthy nations to help resettle refugees. What are the trends? And what do you think wealthy nations—what is their moral obligation? ASH: It's a really important question, Irina. I think we have to understand the obligations of wealthy nations in the context of global responsibility for refugees and displacement. The global rules and norms, the Refugee Convention, was really born out of both a humanitarian and a strategic necessity at the end of World War II and a recognition that unmanaged displacement, unmanaged migration of desperate people, poses extraordinary dangers for those individuals and dangers for the stability of receiving nations, again, many of which are poor and middle-income countries. There are just ten countries representing two and a half percent of global GDP that hosts the vast majority, not the vast majority, over 50 percent of today's refugees. And so while conventional wisdom and watching media in U.S. and European outlets would really lead you to believe that wealthy nations are hosting the vast majority of refugees and asylum seekers, the truth is very different and 90 percent of them are hosted in those neighboring countries. The obligations of wealthy nations are multifold. One in addressing the root causes and really putting shoulder to the wheel and resolving the conflicts that are at the root of the displacement and mobilizing international tools to do so. But also in sharing responsibility for refugees through humanitarian aid, which has, up until this last year, surprisingly leveled off and even declined in the face of rising need. There's now an over 50 percent gap between humanitarian need and the provision of humanitarian assistance. So wealthy nations have not kept pace with humanitarian needs as they've grown. And then another important role is in having generous refugee resettlement and asylum policies that at least match the generosity of those neighboring countries taking so many refugees. I often note that Bangladesh, over the course of three weeks, took in more Rohingya refugees fleeing incredible genocidal violence in Myanmar. They took in more refugees over the course of three weeks than Europe took across the central Mediterranean in all of 2016. And that's a country with barely 1 percent of Europe's GDP. So wealthy nations are quite far behind the generosity of low- and middle-income countries neighboring conflict. And the Trump administration led a global race to the bottom. And that's really, getting back to Beth’s point, the opportunity of the Biden administration. I think it's clear that where the U.S. leads others follow, whether that's a global race to the bottom or whether it's a global race to the top. Under the Trump administration, global resettlement slots dropped by over 50 percent. The number of countries committed to resettling refugees dropped by almost a third. At the end of the Obama administration, anchored by commitments of the Obama administration to raise refugee resettlement and increase humanitarian aid, they achieved a doubling in the first year and a tripling in the second year of commitments to resettlement by wealthy nations, a 30 percent increase in humanitarian aid, and importantly, recognizing trends and protracted displacement commitments from many low- and middle-income countries, who are and always will be hosting the vast majority of refugees, to allow access for refugees to work and to send their kids to school and to be able to rebuild their lives and thrive alongside their new host communities. That's a demonstration of what the leadership of wealthy nations can help drive globally in matching the generosity of those neighboring states to conflict. FASKIANOS: Thank you. Beth, I think given this group it would be wonderful if you could really talk about the role of faith communities working with refugees and migrants in other countries to build on what Nazanin has spoken about. FERRIS: So to follow up on Nazanin's point that most of the world's refugees are not hosted in developed countries but rather in neighboring countries, which [inaudible] they turn to houses of faith, whether its temples, or mosques, or local churches, you know, knocking on the door when you're desperate. At least there's a chance of getting some assistance. As an academic, as a scholar, I'm often struck by how little we've studied these phenomena of faith-based organizations globally. There are lots of good books on the UN and on NGOs, nongovernmental organizations, on government policies. But I suspect if we looked very, very deeply into it, we find that faith-based organizations are in the forefront, that their contributions are rarely counted. I mean, the contributions of a local mosque or church is oftentimes not figured into official aid statistics anywhere. The very first humanitarian crisis I worked on was the Ethiopian famine in the mid-1980s. And I remember standing in Addis Ababa and watching the Canadians deliver hundreds and thousands, I don't know, lots and lots of metric tons of grain, as far as you could see there were trucks piled high with grain. And I said to the guy next to me, I said, “Wow, that's really impressive.” And the guy next to me happened to be an Ethiopian Orthodox priest and he said, “And does anybody mention that there are forty thousand Ethiopian Orthodox congregations that are going to distribute that food? And it's going to be mainly women in our churches who are cooking up the food to serve to needy people.” Yes, the Canadian grain is wonderful and needed, but also those contributions of people working because of their faith are rarely counted in these statistics. And while UN agencies and a lot of international NGOs will come into a community and do wonderful things when there's an emergency, it's the local communities that will be there afterwards. They were there before the crisis, during the crisis, and after the crisis. So I think that giving more power, more resources to local communities to working on issues of accountability and capacity and being able to fill the hundreds of pages of reports that are required by donors are not easy tasks for anyone but for local communities, not so much. But anyway, people have faith and whether it's individual houses of worship or big, huge multimillion dollar organizations like World Vision or the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, these are major organizations that deserve much more attention and to look at the ways that they work together often in responding to emergencies. FASKIANOS: Thank you. Before we go to questions to the group, I want to get in one more question. President Biden has made climate one of the central areas of his focus. And we talk a lot about the violence that is driving immigration. But climate is definitely increasing and is going to be part of this global migration trend. So Krish, can you talk about the effect of climate on migration patterns, climate-induced migration? What is it? What are understood as the domestic international consequences and challenges, and how is that relating to U.S. refugee resettlement? VIGNARAJAH: Yes, thank you for the question because I do think it is a trend that we're already seeing, and it's going to be a trend that will continue to grow exponentially. So right now, we know the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, UNHCR, has said that about an average of 22.5 million have been displaced by climate each year between 2000 and 2018. That number is going to continue to rise. The International Organization for Migration has indicated that by 2050, there will be two hundred million climate-displaced persons. The global displacement obviously is a record high today, and while the need to migrate due to political instability, persecution, and economic reasons has always been present, and as Nazanin noted, it is still the majority of why people are migrating. We're seeing more and more people on the move due to extreme weather events. So, at present, about one-third of those displaced worldwide are forced to flee by sudden onset weather events. And by 2050, twenty-five million to one billion people are expected to be displaced by climate-related events. So this is a stark reality that we face today, and we need to act with urgency knowing the reality is that no country in the world has recognized a separate legal pathway to accept climate-displaced persons. In our own hemisphere when we talk about the northern migration coming from Central America, it's really important to recognize that 42 percent of El Salvadorans currently lack a reliable source of food in large part due to climate-exacerbated drought and crop failures. The region has equally been battered by consecutive climate-fueled hurricanes that have displaced hundreds of thousands of people. And the reality is that there is an interplay between the traditional factors that are recognized like war, violence, and persecution. And it's something that we are experiencing here at home, whether it's Western wildfires, hurricanes or other natural disasters, we're starting to see climate-induced migration here in the U.S. Historic wildfires on the West Coast, tropical storms, hurricanes in the Southeast are the kinds of extreme weather events that have forced Americans to truly consider in a personal way what displacement and relocation looks like here at home. And just to kind of contextualize this, because I do actually think that this might foster empathy, maybe we don't know what it means when a country is engulfed by civil war in a way that you literally must flee your home. But more than 1.2 million Americans were displaced in 2019 because of climate and weather-related events. And thirteen million could be displaced by 2100 due to sea-level rise and other natural disasters. So this is an issue that we are facing here at home and across the globe, and one that we need to address. It is heartening to know that the administration, through an executive order, recognized that this is an issue that not just needs to be studied but needs to see action. FASKIANOS: Thank you. So I just want to give an opportunity to either Nazanin or Beth to comment on the climate issue before we turn it over to the group for their questions. FERRIS: I can jump in. I certainly agree with Krish that the projected numbers of people displaced by climate are going to be far higher than we've seen in the past. But it's a complicated issue. We had hurricanes before human-induced climate change, separating out who's been displaced by climate versus normal. Environmental variation is a tricky thing. And then there are kind of ethical issues: Should people who are displaced by sea-level rise or hurricanes be given preferential access to a country compared to those who suffer a volcanic eruption or an earthquake? So these aren't easy issues, but I think we've got to begin to address them and ask these questions. And I'm encouraged that the Biden administration has asked for a report on climate migration in one of his very first executive orders. So lots of people are working on this. FASKIANOS: Nazanin? ASH: Nothing to add on the climate front. I did want to come in on Beth's earlier comments on the role of faith communities, but I'm also happy to give the floor to questions and come back to it later. FASKIANOS: Why don't you just—it would be great to also—since this group is very diverse, I would love to hear your views on the interplay of faith. ASH: Sure, well, I just wanted to emphasize what both Beth and Krish have said and give an example from our own experience here in the United States. I mean, we're living in a period of, as Krish said, extraordinary politicization of refugee policy and asylum policy. But it really is inconsistent with what's been a long bipartisan history and a welcoming tradition in the United States for refugees, certainly, since the 1980s. And, as there's been such a politicized debate at the federal level and an appropriate amount of attention on the real destruction of the Trump administration to refugee resettlement, asylum and then immigration policy, I think what's been missed is the sea change of support that's happened at the state and local level driven by faith and community organizations. And so the International Rescue Committee operates on the ground in twenty-five cities across the United States—they're red, and they're blue, and they're purple in their politics—but they're all very much defined by their welcome. And we have refugee resettlement sites where in the last few years of the Trump administration, volunteers outpaced the number of refugees by two to one. And those faith communities, the private sector, and state and local elected officials have collectively in their advocacy turned back over a hundred state-led anti-refugee policies and implemented a total reversal such that last year the number of pro-refugee proposals at the state and local level outpaced negative ones by seven to one. So states are really leading the way in policies of welcome, in policies of integration and support, and creating pathways for refugees and other immigrant populations to access education more quickly, to access the job market, fill crucial gaps in health and in hospitality and in our global food supply chains. So states are really leading the way supported by their faith communities. And it's really different than what we hear at the federal level. And, just a final point on that front, support for refugees and for the U.S. as a place of welcome is higher in many ways than it's been in years. So a solid majority, 73 percent of Americans, believe the U.S. should be a place of refuge. And that's driven by an 18 percentage-point increase among Republicans over the last two years. And again, that's very much rooted in the advocacy of faith communities across the United States. FASKIANOS: Thank you. Wonderful way to end our discussion. We are going to go now to all of you for your questions. So Grace, if you could give us the instructions, that would be wonderful. OPERATOR: [Gives queuing instructions] We will take the first written question from Homi Gandhi of the Federation of Zoroastrian Associations of North America, who asks, “Where do you place the major responsibility for creating this displacement? Is there a penalty for those responsible for creating the situation? Who should enforce that penalty?” FASKIANOS: Beth, go ahead. FERRIS: I can go ahead on this one. It's usually oppressive governments that violate the rights of their citizens or warring parties in the conflict, at least those displaced by conflict. Right now, our system doesn't do a good job of holding governments responsible when they displace people. The first case to go to the International Court of Justice was filed last year, and really charging Myanmar, for example, for its responsibility for displacing close to a million Rohingya into Bangladesh. That's going to be a really important case. It’s supposed to get some preliminary decision this summer. But, so far, governments have been able to displace people in their countries with virtual impunity. When it comes to climate change and disasters, responsibilities are more diffused. Certainly those who emit large amounts of gas are responsible for global warming, but usually don't feel a corresponding responsibility to accept those displaced by the consequences of their actions. So in terms of responsibility for displacement, we have a very, very weak international system. FASKIANOS: All right, we'll go next question. OPERATOR: Our next live question will come from Simran Jeet Singh of YSC Consulting and Union Theological Seminary. SINGH: Thank you for your expertise and for sharing your insights. It's been a great conversation. My question—I submitted it as a written question as well— we were talking a bit about specific countries where a majority of the refugees are coming from some of the worst violators of human rights. And so in some of these places a lot of these communities are targeted for their faith. And so the question here is what would it look like for the Biden administration to prioritize refugees fleeing religious persecution in particular? And I'm asking this because today because in addition to our conversation around the Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar, I'm thinking about Hindus and Sikhs in Afghanistan who are left vulnerable as the U.S. pulls out of that region. Thank you. VIGNARAJAH: I can start—oh, no, no, Nazanin, go ahead. ASH: Go ahead, Krish. VIGNARAJAH: I'll just quickly answer and then hand it over to my very learned colleague, Nazanin. It is a great question because I do think that there are certain areas of refugee resettlement that have especially strong bipartisan support. And I'd like to believe that this is one of those areas. Thankfully, the Biden administration did remove some of the restrictive eligibility categories that the Trump administration had imposed where, you know, that there is a virtue to having regional allocations as opposed to specific categories. But I also realized that there is a benefit to signaling the importance of religiously persecuted refugees because I do think that they garner strong support. I think that this is an area where we could use this to expand the number of refugees accepted under the presidential determination. But our view is that the regional allocation giving Asia and regions that, for a variety of reasons, do have a significant number of refugees does afford us an opportunity to respond. I also believe and I know that there's been a few questions on this issue of Afghanistan. This is going to be a central focus, certainly for us, and I think of some of our colleagues in advance of September 11 because we know that we can't wait until September 10 in order to sufficiently address the need. We have to recognize that those who advocated for democracy, who advocated for religious open-mindedness, frankly, who even advocated for gender equality are going to be targeted because of Western values. So I think that this is an area where there needs to be strong advocacy and real focus because I do think that there is a lot of support. And I think that there's a dire need of individuals who are really going to be targeted between now and then. FASKIANOS: Nazanin, do you want to pick up? ASH: I can add to that, and Beth, I know you will have deep scholarship to add to this, too. I mean, just to say that prioritizing those fleeing religious persecution and those who have been targeted on the basis of their religion or their politics is built into the refugee definition. It has been a central driving force, especially in U.S. refugee policy. So I'm thinking about specific legislation that has created programs like the Lautenberg Program that assists refugees who've been religiously persecuted or priority categories that have been created for some religiously persecuted populations to access the Refugee Resettlement Program. A number of those priority categories are under consideration in the Biden administration's executive orders examining ways to expand the pathways to protection for precisely the populations you're identifying. And then as Krish talked about there is special focus right now on planning for and creating pathways to protection for those in Afghanistan persecuted on the basis of their religion or their politics in the run up to the anticipated troop withdrawal. And I'd also add to what Krish said to note that some of those policy proposals are looking at even more immediate channels than what's available through the Refugee Resettlement Program where you can often wait months and even years for background checks and security vetting procedures or where even embassy referrals and priority categories can take a long time to process. But the advocacy from our community has been around the urgent need for an emergency response recognizing the imminent danger for some populations. FASKIANOS: Thank you. Let's go to the next question. OPERATOR: Our next written question is from Elaine Howard Ecklund from Rice University, who asks, “How can faith communities advocate for the rights of refugees and immigrants more broadly, especially in the midst of the pandemic?” VIGNARAJAH: So I can start there. The reality is that 99 percent of us trace our ancestry to another nation, right, and I think that, as I mentioned earlier, so many faiths in different ways believe that welcoming the stranger is a matter of faith or religion. I do think it's really important for these communities to be particularly vocal, especially because we have seen some evangelical communities that have taken a strong stance in opposition to immigration. And so my view is that if we can invoke scripture, if we can try to find some commonality and try to use that as a starting point, it could help. We've got work ahead of our ourselves, and we realize that public support does impact the policies. By some accounts, immigration is more popular today than it's ever been if you look at the Gallup poll that shows that nearly 8 in 10 Americans believe that immigration is a good thing for our country. But if you look at other polling it suggests that the executive order that the president signed on refugees was his least popular executive order, that there was actually more opposition to it than support. And this is where I think that faith communities, hopefully, will continue to be strong ambassadors in their communities for why this issue is important to them as a matter of religion. I think this is also why the previous question on religious persecution is an important hook. Because there are clear communities like the Chin Christians that I've spoken to members of Congress on both sides of the aisle where they do believe that it is important for us to engage. In terms of the pandemic, I think that the two areas that I would highlight are one, I think all of us have spoken on the presidential determination. It took some effort to get to that figure right now of sixty-two thousand five hundred. It will also take some effort for us to get to the figure of one hundred twenty-five thousand, which is what President Biden pledged to as a candidate. So we need to continue to be vocal and show to the White House that this is an issue of importance to us. And then the other piece is Title 42, which is still being used. It's basically an emergency order indicating that because of the pandemic, individuals seeking to exercise their legal right at the southern border can be turned away. As we as a nation get to a better spot we need to look closely at that policy, and it needs to be lifted. So I think that faith communities can play an active role here as well. FASKIANOS: Beth, you have anything? FERRIS: I'll just kind of build on that. I think what we've seen both with refugee resettlement and immigrants in the U.S, it can be a great interfaith endeavor. I mean, a lot of times religious groups that don't have a lot in common with each other theologically can come together to furnish an apartment or to help a family or to make sure that something concrete is done. I think in those tangible efforts of working together we’re really moving toward more interfaith action, which is good for lots of reasons in this country, not least to overcome some of the terrible anti-Muslim and other religious sentiment that we've seen in recent years. FASKIANOS: Thank you. Let's go in next question, Grace. OPERATOR: We will take the next live question from Frances Flannery at Bio Earth, LLC. FLANNERY: Oh, thank you so much for discussing climate displacement and the two hundred million to one billion anticipated climate-displaced persons by 2050. But even if this is a current priority in the Biden administration, how can we face this enormous problem over so many coming decades in the U.S. considering that the political parties in the White House will alternate, especially since the U.S. plays an outsized role in influencing the actions of host countries? And what I'm wondering is can faith communities play that role of adding more stability to the response between now and 2050 so that we can be proactive with what we know is coming? Thank you so much. FASKIANOS: Go ahead, Krish. VIGNARAJAH: Sure. Yes, I certainly think that faith communities can play a critical role here of highlighting that, again, this is a nonpartisan issue. This is not an issue that should feel foreign to Americans because whether it is the Indigenous population living off the coast of Louisiana, on Isle de Jean Charles, which are literally getting federal taxpayer dollars today as they prepared to resettle due to sea-level rise, or the Indigenous population in Shishmaref, Alaska. This is an issue that is coming home and is felt by, I think, all Americans. The fact that climate denial is slowly decreasing as people are literally feeling the impacts in their own backyards is unfortunate. But it is an opportunity. My hope is that America can actually lead the charge by creating two pathways for climate-displaced persons. One would be a permanent solution, which, candidly, as you highlight the politics, that is going to be a heavier lift. And that would actually be to create an allocation for those who literally lose their home. When New Zealand tried this and they tried to create a humanitarian visa, it's important to recognize that it ultimately failed because there was a recognition that for these individuals affected, this was the issue, it was the option of last resort. No one wants to flee the only home that they've known. And so part of the solution needs to be in creating a pathway for those who no longer have a home. Another needs to be creating a temporary protected status for those who are affected by a sudden onset disaster. And I think that this is where faith communities can highlight kind of their support for finding solutions. FERRIS: A lot of people are moving away from talking about climate change displacement to focusing on disasters because it's less politicized. People may not agree with climate change, but they can agree that the flooding is getting worse every year. So talking about flooding somehow is easier to deal with than big climate change and questions of who's responsible and so on. I think we also need to recognize that migration is adaptation to climate change. It's a way of people surviving. If your land is no longer habitable, you move. There's nothing new about this. We've had people move for environmental reasons from the Maya, from the Romans. I mean, for thousands of years people have moved in response to drought and famine. And yes, it's getting worse and likely to get worse because of climate change, but I think that trying not to make it this huge, insurmountable crisis, we can deal with this. We know what's coming. We have the tools. We have the will. This isn't some huge threat hanging over our head. Sometimes I think that advocates that are working on climate change really do a disservice by overhyping the threat of migration. I remember Archbishop Desmond Tutu, who's a great human rights champion, saying something to the effect of, “If you rich countries don't stop your global emissions, you're going to have millions of people turning up on your border.” Let's stay away from that language of migration as a threat. I mean, migration is normal displacement. When people are forced to leave their homes it’s bad, and we should try to prevent it. But not everybody who moves because of the effects of climate changes is a threat. FASKIANOS: Next question, please. OPERATOR: We'll take the next written question from Bruce Compton from the Catholic Health Association, who asks, “It is my understanding that most migrants and refugees do not desire to leave but economic and social factors force them to seek refuge. While being welcoming under those circumstances is imperative, how do we best address the root causes? How are your organizations involved in this work?” ASH: I can start on that answer because I think it's a really, really important question not just for our organizations in their work we're doing but, as I referenced at some point in this discussion, for the global community. The International Rescue Committee does an annual watch list of countries. It’s the twenty countries most at risk of descending into further crisis with greater humanitarian consequence. The twenty countries on our watch list this year account for just 10 percent of the world's population, but they account for 85 percent of all humanitarian need and 84 percent of refugees. So it just gives you a sense that as vast as the challenge can seem flipped on its head, it's about bringing new approaches and all of our international tools and resources to bear on resetting the conflict in twenty countries, putting those conflicts on different and sounder footing, and getting to a place where the humanitarian needs of those populations are met. That's, as Beth and Krish talked about, is what people on the move are seeking. They're seeking safety. They're seeking survival. They're seeking the basic things that they need to be able to create security and achieve the human potential of themselves and of their children, and so providing the social and economic and political underpinnings for responsive government and inclusive government that meets the needs of all their people. Providing it is a weird statement to make because it can't be provided from the outside but creating the incentives, organizing international assets and diplomatic interventions to achieve that outcome, including for addressing challenges like climate change, right, adapting and addressing the needs of your population and the challenges that they're addressing is a responsibility of states to their citizens. And so where we have fragile, oppressive, belligerent, unaccountable governments, you see the proliferation of conflict and displacement. And so that's a critical part of addressing the root causes. And to say one more thing about that, I mean, the challenge we have now, as Beth alluded to earlier and as what's prompted by the first question from participants today, is very little accountability for oppression and non-responsiveness to the needs of your citizens. Many of our international tools think about the UN Security Council and our other conflict resolution tools were built to resolve conflicts between states, again, that post-World War II context of resolving conflicts between states when the vast majority of conflicts today are within states. There are civil wars with sometimes as many as forty-plus internal actors and parties to conflict and violence. And it's incredibly difficult for sort of our traditional global tools and norms to reach into those conflicts and hold nonstate actors or belligerent states who hide behind the assumed protection of sovereignty to help resolve some of those conflicts and insist on accountability for the protection of their citizens. But it's increasingly what the international community needs to do. FASKIANOS: Okay, we'll go next question. OPERATOR: We'll take the next live question from Tom Getman of the Getman Group, the World Vision director, and Senate and UN staffer. . GETMAN: Hello, friends. Could I segue on my colleague Beth's earlier comment and could you please give us some sense of how the COVID crisis has added to or taken from the Good Neighbor programs like here on Capitol Hill that facilitate LSS and LRS resettlement of Afghans and El Salvadorian refugees? These special visas of former endangered employees of the U.S. military or State Department still have needed urgent attention even during the Trump era. And it increased Christian, Jewish, Muslim, and even Mormon cooperation here on the Hill—remarkably, more money, more involvement, more setting up of apartments. Is this common across the country? It's certainly has increased prep for soon increases of regular arrivals. Thanks a lot. VIGNARAJAH: Sure, so I'm happy to jump in there. Tom, it's a great question because it is one of the blessings of my job. Even in 2019 I had the chance of going to the southern border. And while it felt at that time like a war on immigration and immigrants, I got a chance to see the interfaith effort there where you would see a Lutheran working alongside a Catholic working alongside a Jew working alongside an Episcopalian. And to me the idea of some immigrants who may have been fleeing religious persecution, to see and be welcomed into a nation where so many people of faith work alongside in this critical work of welcome, to me that's inspiring and to me that is American. So it is not unique in terms of what you're describing. And in fact, we have a program called Circle of Welcome. The idea is that it's critically important for us to engage non-faith communities that are the community-based anchors, pillars of their community, knowing that this work is not done in a few months’ time or even a few years’ time. I just want to touch on the SIV issue because I know that it also came up, I think, in a couple other questions. This is an area of critical importance. I know that Nazanin also mentioned this because it is going to be something we need to work on and really ramp up our advocacy and highlight that faith communities feel very strongly alongside national security officials and allies because we have more than seventeen thousand Afghans, who, for those of you who don't know, SIVs, or special immigrant visas, they are given to individuals who served as an interpreter, a driver, alongside our military as we have troops deployed, particularly in Afghanistan and in Iraq. And we know that when we talk about this population, looking at Afghanistan specifically, we have the seventeen thousand that I've identified, but also their family members who also become targets. That total is estimated at about fifty-three thousand. So we're talking about a population that is narrowly defined at least seventy thousand individuals. And so one of the things that is critically important for us to put the pressure on the administration to think through now, as Nazanin mentioned, this is a years-long process. And so what policy solutions can organizations like CFR be a leader working alongside immigration organizations like IRC and LRS to advocate? We strongly believe and we've actually sent a letter to the White House indicating that just as we've done in the past these individuals should be evacuated to American toward territory like Guam where they can be processed and ultimately resettled to the United States. But this is an area where I do believe, to your comment, there are a number of faith communities who strongly believe that this is a priority area. And then hopefully, we can see some results not just in the next few months’ time, but really in the next few weeks' time. FASKIANOS: And I'm going to go to—oh, go ahead, Beth. FERRIS: In Biden's executive there was a lot of emphasis placed on moving people who have been waiting for far too long for these special immigrant visas. I think many of us are deeply worried about Afghanistan and what's going to happen when U.S. troops withdraw. Will there be increased persecution of those who've worked with Americans? Will there be new refugee outflows? This is one of those cases where the early warning signs are all there. I mean, we should be thinking and preparing and in case the worst happens we need to take early action when we see these dangerous signs. FASKIANOS: Thank you. Next question. OPERATOR: We'll take the next written question from Guthrie Graves-Fitzsimmons from the Center for American Progress, who asks, “What religious arguments do you hear against welcoming refugees? And how do you challenge those arguments?” VIGNARAJAH: One of the most insidious arguments that I have heard is actually one that Attorney General Jeff Sessions used in justifying the family separation policy. It was essentially invoking scripture to say that God requires us to follow the rule of law. And so if you don't, apparently anything goes. And first, I think, it's important to recognize that those families that are seeking asylum are obviously seeking legal relief. It is legal to present at the southern border. And second, in no circumstance is family separation justified in my mind as a policy. So I think that that is one of the worst ways in which I've seen religion used by anti-immigration advocates. FASKIANOS: Okay, next question. OPERATOR: We'll take another written question from Reverend Canon Peg Chemberlin, founder of Justice Connections Consultants, who asks, “Could you comment on the level of anti-refugee movements in other countries as compared to the U.S.?” FERRIS: I'll take a stab at that. I mean, it varies a lot from country to country and from time to time. Even in the United States if you look back over the past two hundred years, you see periods of apparent welcome but also always a little bit of anti-immigrant sentiment whether it was the Know Nothing Party in an earlier time. But, it's never been pure welcome nor has it ever been pureanti-immigrant, everybody-stay-out sort of mentality. So you see different things in the United States. And similarly in Europe you have the rise of these right-wing populist parties, spurred in part by the 2015 arrival of over a million refugees, asylum seekers, and migrants in Europe, really fueling these questions around identity and culture often mixed in with religion not wanting Muslims to come to “our” country because we consider ourselves to be a Christian country, even if, in fact, they're actually a pretty secular country. So, I mean, there have been these kinds of reactions. You also see it in countries hosting large numbers of refugees, whether it's Lebanon or Jordan or Turkey where you see attitudes after a while become less welcoming even when initially the population was supportive of the refugees coming. It just kind of natural. People overstay their welcome. It's what Nazanin named talked about in the beginning about these protracted situations. I remember one time in Lebanon in the Beqaa Valley talking to this older woman of a very modest background who had a little tiny shop who said, “Two years ago, I saw a Syrian couple and a toddler walking in front of my house. And because of my faith, my Muslim faith, I knew I had to welcome them, but there was no room. So I said, you can stay in this shanty out back of my house because it's better than sleeping on the road.” And then she said, “That was two years ago. Now there are twenty-two people back there. There's no running water. There's no toilet. I want them to leave, but I can't tell them to go back to Syria.” And so you see that this natural solidarity and hospitality when time goes on, it's natural, it wears out. And so that's where I think the international community really has to step up in these protracted situations. ASH: I got two things to what Beth noted. One, how much political leadership matters. So if you think about the differences across Europe and you consider the comparison of Angela Merkel versus Viktor Orban, or where you look at our own politics here in the United States and where in a very limited amount of time, I mean, over the course of a year you had a single leader who really politicized refugees and disrupted a forty-year bipartisan political consensus on the U.S. as a place of refuge for those fleeing violence and persecution. So I think that political leadership matters a lot. I also think policies matter a lot to managing the reactions of populations as Beth has noted. I think, in the U.S. when you look across polling what's really fascinating is, as I noted earlier, by wide majorities, Americans believe the U.S. should be a place of refuge, but they also want to know that the process is orderly. They want to know that it's secure. And so, support for refugees rises with the knowledge of what the process is, how refugees are vetted, how they're supported to integrate when they arrive, and how they're economic contributors. The same is true, as Beth is talking about, in countries all over the world where they face the same domestic political challenges in hosting large numbers of refugees but where the actions of leaders can help frame the narrative in important ways and where policy is domestic and with the support of the international community can help ease the impacts on host communities and ensure that we create the conditions where, again, communities can thrive together, old and new. FASKIANOS: Thank you. Let's take the next question. It'll be the last question. OPERATOR: We'll take a live question from Katherine Marshall of Georgetown University. FASKIANOS: Katherine, you need to—yes, there you go. MARSHALL: Looking at the sort of foreign policy aspects of this and maybe looking at a specific case, what can religious communities collectively and individually do to address some of the long-standing issues in Central America that are such a such a cause of the migration crisis at this point? FASKIANOS: Why don't I let each of you take a pass at that since this is the last question and it allow you to leave us with your answer to the question and leave us with one final word. So should we go—Beth? FERRIS: I can jump in. Yes, I mean, I think that churches and other faith communities in Central America have an important role to play in terms of addressing problems of governance, in terms of corruption, in terms of education, in terms of addressing poverty. This is a tall order. I think that the situation, these causes are complex, and they require more than local communities can provide. So I hope to see a very robust response by the Biden administration to addressing the causes. And my final comment would be that, yes, it's really important to have welcoming policies to immigrants and refugees, but also important to address those causes that force way too many people to flee their communities. FASKIANOS: Krish? VIGNARAJAH: Sure, we know that when it comes to refugees even under the most kind of generous and welcoming conception of a functioning refugee resettlement infrastructure, only 1 percent of refugees will be resettled. So to the extent that as a matter of foreign policy and as a matter of faith, America exercises its global humanitarian leadership when it has a robust refugee resettlement and immigration system. I think that's critically important for faith communities to be actively engaged in highlighting that obviously this is not just the right thing to do, but it's also the smart thing to do. And appreciate with an audience like here at CFR highlighting that when we talk about population decline and what we can learn from Japan and the stagnation there that the census numbers have shown us that immigration is a part of our foreign policy solution. When we're talking about what some may describe as a cold war with China, being welcoming of dissidents who may be actively expressing their frustrations in Hong Kong is a tool of our foreign policy. But I think as Beth has mentioned, I think each of us has highlighted we know that the root causes have to be addressed because that is the bulk of the way by which we respond and help those who, frankly, aren't as lucky and don't hit the jackpot and come here to the United States. That is where I think that the active communities, particularly in our own hemisphere, of the sister churches in Central America, are certainly a way in which we can actively engage to the extent that there's dysfunction in some of the governmental structures. We know that the churches and other faith institutions are critical pillars of their community. And my hope is that there are nongovernmental ways in which we can exercise support to stabilize these regions as well. ASH: Yes, maybe I'll just add—we're over time so let me know, Irina, even if you'd like to pause? FASKIANOS: No, I would like you to conclude. ASH: Going from the global to the local, I mean, the foreign policy imperative for responding here is so clear. When countries are not supported and equipped to receive refugees and asylum seekers fleeing immediate violence and persecution, it results in additional humanitarian and political crises. Of the fifteen largest returns that have happened since the 1990s, a third of them have resulted in the resumption of conflict. So if we just consider how much worse the Syrian crisis would have been if Jordan, Turkey, and Lebanon turned back five and a half million Syrians? How much worse the crisis in Myanmar would have been if Bangladesh refused the nearly one million Rohingya who crossed their borders in an extraordinary short amount of time? If Colombia returned the over one million Venezuelans to a very unstable Venezuela? If Kenya returned three hundred thousand Somalis to an unstable Somalia? Pakistan, two million Afghans to an unstable Afghanistan? You see the foreign policy imperative in responding to displacement and refugee crises. It's about stabilization as much as it is about humanitarian response. At the local level, again, as Krish and Beth have said, it's been faith communities and local organizations that have seen the writing on the wall that have taken in their neighbors and that have provided that first round of welcome and support. But if that's not supported and sustained with the resources of wealthy nations in the international community, we see these protracted contacts, we see welcome wearing thin, and we see populations moving on. What I think is so interesting about the Central American context is that it's indeed churches and faith groups that have provided that essential safety, security, food, shelter, water along migration routes, but it's been about the conversion of your church to provide for some temporary assistance to migrants as they're passing through. If those efforts were sustained and expanded such that Central Americans moving to that safe community were supported there and given opportunity there and given a leg up there and able to go to school and begin work anew in those communities, the work of those faith leaders could be extended from something that's been a temporary safe home on your route to something that is about expanding the ability of local communities to provide refuge and to help integrate those who are internally displaced. FASKIANOS: Thank you all. I apologize for going a bit over, but I wanted to give each of you a chance to sum up. This has been a very rich discussion. Thank you for your devotion to these issues and your work over the years. It is really heartwarming to know that that so many people are working on this issue and it's so important. So thank you all, I really appreciate it. Nazanin Ash, Elizabeth Ferris, and Krish O'Mara Vignarajah—we appreciate it.

-

Attacks Against Security Facilities Accelerate in Former BiafraOn April 5, gunmen attacked a prison in Owerri, Nigeria, freeing 1,844 inmates. (Owerri, the capital of Imo State, is a major trading center with more than one million residents.) On April 6, “bandits” stormed a police station in Ehime Mbano, also in Imo State, freeing detainees. No group has claimed responsibility, but police say the likely perpetrators are the Eastern Security Network, the armed wing of the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB). President Buhari, in London for medical reasons, characterized the perpetrators as “terrorists”; the army pledged to “flush out the miscreants” from the region. Vice President Yemi Osinbajo arrived in Imo State yesterday to assess the damage in Owerri. Imo is mostly Igbo and Christian in population. It was the heartland of support for an independent Biafra during the 1967-70 civil war. Since then, successive federal governments have taken a hard line on separatism. Since 2015, when Buhari, a northern Muslim, was elected president, separatist sentiment has been growing. The movement of Muslim, ethnically Fulani herdsmen into the region looking for pasture has exacerbated the situation, as has the influx of mostly Muslim internally displaced persons fleeing Boko Haram in the North East. Some advocates for renewed Biafran separatism claim an Islamic plot, abetted by the Buhari government, to place all of Nigeria under the crescent. The jailbreaks will likely increase violence and insecurity in Imo State. It should be noted, however, that pro-Biafra sentiment is not widespread in the adjacent oil patch in the Niger Delta, specifically Bayelsa and Rivers States. The low-level insurrection in the Niger Delta has different drivers.

-

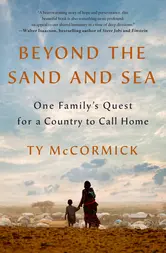

Beyond the Sand and Sea

![]() From Ty McCormick, winner of the Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award, an epic and timeless story of a family in search of safety, security, and a place to call home.

From Ty McCormick, winner of the Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award, an epic and timeless story of a family in search of safety, security, and a place to call home.

-