Refugees and Displaced Persons

Archive

168 results

- Backgrounder

How Does the U.S. Refugee System Work?

![]()

- Backgrounder

How the U.S. Patrols Its Borders

![]()

![]() By Will Freeman

By Will Freeman![]() By Michelle Gavin

By Michelle Gavin![]() By Ebenezer Obadare and Reina Patel

By Ebenezer Obadare and Reina Patel![]() By Jeremy Sherlick and Diana Roy

By Jeremy Sherlick and Diana Roy![]()

Where Are Ukrainian Refugees Going?

Video TypeBy Diana Roy and Thamine Nayeem![]()

Where Have Afghan Refugees Gone?

Video TypeBy Lindsay Maizland and Thamine Nayeem- By Lindsay Maizland

![]() By Stewart M. Patrick

By Stewart M. Patrick![]() By John Campbell

By John Campbell![]() By John Campbell

By John Campbell- By Paul J. Angelo

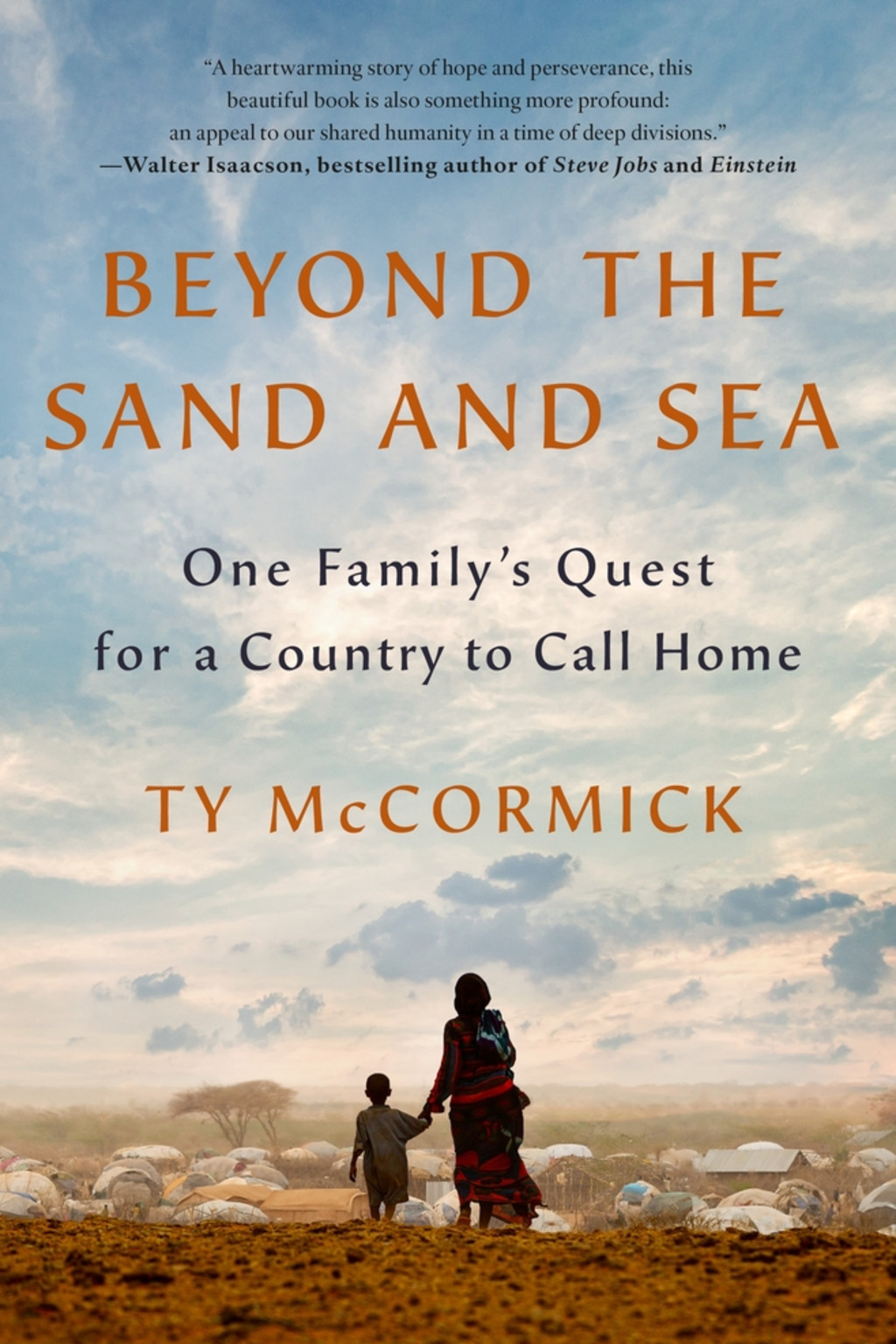

![Book cover for Beyond the Sand and Sea, a woman and a small child holding hands, walking through a desert with a large blue sky with wispy clouds]()

Beyond the Sand and Sea

Ty McCormick

![]()

The COVID-19 Risk for Refugees

Video TypeBy Anna Gratzer![]() By John Campbell and Jack McCaslin

By John Campbell and Jack McCaslin![]() By Center for Preventive Action

By Center for Preventive Action