NATO’s Turkey Ties Must Change

The Turkish invasion in northern Syria is the latest example of the country’s disregard for NATO values. It’s time to do something about it.

By experts and staff

- Published

Experts

![]() By Max BootJeane J. Kirkpatrick Senior Fellow for National Security Studies

By Max BootJeane J. Kirkpatrick Senior Fellow for National Security Studies

President Donald J. Trump may have thought that he was doing Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan a favor by agreeing to move U.S. troops out of northern Syria, thereby allowing the Turkish military and allied Arab militias to invade Kurdish-controlled areas. But in so doing, Trump has plunged U.S.-Turkey relations into a greater crisis than ever, and raised fresh questions about whether Turkey still belongs in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

No Longer a Reliable Partner

Relations between Turkey and the rest of NATO—forged in the 1950s when Turkey had a secular, military-dominated regime—have been growing tense for years as Erdogan has consolidated his power and that of his Islamist Justice and Development Party (AKP). He has destroyed the last vestiges of Turkish democracy, purging secular, pro-Western military officers and intellectuals. Erdogan has become a leading supporter of the Muslim Brotherhood, and has made common cause with jihadis in Syria. He has refused to abide by U.S. sanctions on Iran and has drawn closer to Russia. Turkey’s decision to purchase a Russian S-400 air defense system led the Pentagon in July to boot Turkey out of its F-35 fighter program. Media outlets aligned with Erdogan have put out vitriolic anti-American propaganda, blaming the United States for an attempted military coup in 2016 and for providing asylum to Turkish cleric Fethullah Gulen.

Now the Turkish invasion of northern Syria has brought worsening relations to a head. Turkish artillery fire landed close to U.S. troop positions and Turkish-allied militias have reportedly committed atrocities against the United States’ Kurdish allies. Trump threatened that “if Turkey does anything that I, in my great and unmatched wisdom, consider to be off limits, I will totally destroy and obliterate the Economy of Turkey.” He later announced that the United States would raise tariffs on Turkish steel, halt ongoing trade negotiations, and impose sanctions on top Turkish officials. It’s questionable whether U.S. sanctions could have a devastating effect—Turkey is the United States’ thirty-second-largest trading partner. But that Trump is now threatening to “obliterate” the economy of a NATO ally shows just how incongruous Turkish membership in the alliance has become.

How to Treat Turkey

If Turkey applied for NATO membership today, it wouldn’t get in the front door. NATO’s Membership Action Plan “requires candidates to have stable democratic systems, pursue the peaceful settlement of territorial and ethnic disputes, have good relations with their neighbours, show commitment to the rule of law and human rights, establish democratic and civilian control of their armed forces, and have a market economy.” Turkey has a market economy but doesn’t meet any of the other criteria. Yet, NATO lacks any mechanism to kick out an existing member.

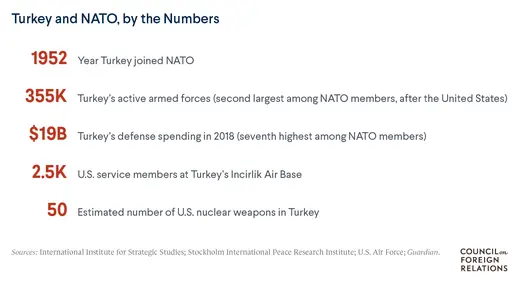

Even if Turkey remains in NATO, the United States and other members in the alliance need to give up the illusion that Turkey is a reliable partner. They should treat Turkey as a “frenemy,” to adopt the term that has been applied to Pakistan, another wayward U.S. ally. There will still be issues on which Ankara and Washington can cooperate, but Turkish interests have diverged radically from those of the United States. CFR President Richard N. Haass argues that, because of this, the United States “should withdraw all nuclear weapons, reduce reliance on Turkey’s bases, and restrict intelligence sharing and arms sales.”

Those are all good ideas, and the place to start is at the Incirlik Air Base in Turkey. It was built by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in the early 1950s, and U.S. and other NATO allies’ aircraft have been using it ever since as a crucial regional base for surveillance, disaster relief, airlifts, and combat operations. But it’s time to move on. The U.S. Air Force should relocate its aircraft to Muwaffaq Salti Air Base in Jordan and to other bases in Persian Gulf countries. The tactical nuclear weapons stored at Incirlik should either be brought back to the United States or relocated to more reliable NATO countries.

It’s time to get real about Turkey instead of assuming that relations can remain as close as they were during the Cold War—which ended twenty-eight years ago.