Empowering Refugees in Times of Crisis

To address a migration emergency that shows no signs of abating, states should look beyond building refugee camps and offer economic opportunities to those displaced, says expert Alexander Betts.

By experts and staff

- Published

By

- Jesus RodriguezCFR Editorial Intern

- Alexander BettsDirector of the Refugee Studies Centre, Oxford University

The United Nations estimates that there are now about 22.5 million refugees, 5 million of whom are Syrians who have fled civil war. Governments have traditionally managed refugee inflows by setting up camps, but this age-old strategy has run its course, says Alexander Betts, director of the Refugee Studies Centre at Oxford University. “We need a paradigm shift—one that is not based on seeing refugees just as having vulnerabilities, but one that recognizes their capacities,” he says. For instance, countries like Uganda and Jordan have expanded employment opportunities for refugees, he explains. “The key to creating sustainable solutions for refugees is to move beyond warehousing people indefinitely year on year,” Betts says.

How did the migration crisis get to this point, and what are its driving factors?

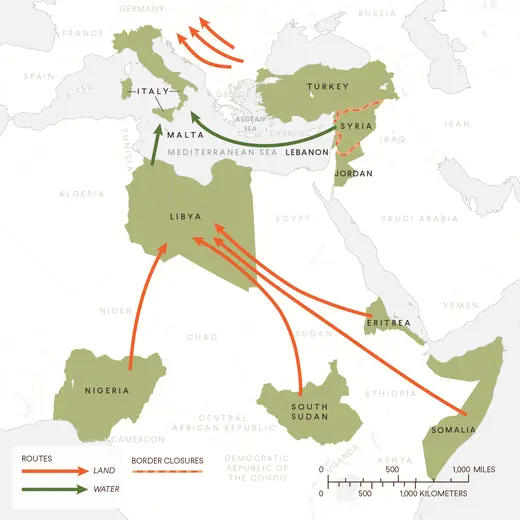

We first became aware of the idea of a refugee or migrant crisis from about April 2015, and what changed at that point was an increase in the number of those coming to Europe from outside the European region, and in particular, the influx of around a million asylum seekers, with the largest category coming from Syria.

Since then, the nature of that crisis has changed from a focus on Syrians and other populations crossing the Aegean Sea from Turkey and coming through the Balkan route toward a focus on movement across the central Mediterranean from sub-Saharan Africa. The crisis we’ve been seeing, particularly this summer, has been a movement of people from the Horn of Africa and West Africa through Libya and across the central Mediterranean crossing to Italy or, to a lesser extent, Malta.

A lot of what happened in 2015 was driven by the Syrian crisis and the breakdown of adequate protections for Syrians in Jordan, Turkey, and Lebanon, all of which had a decline in [received] humanitarian assistance. What we see now are mixed migratory movements stemming in part from fragile and failed states like South Sudan, Somalia, Eritrea, and Nigeria, but also the movement of people seeking economic opportunity, particularly from West Africa, trying to use smuggling routes to get across to Europe. And those movements across the central Mediterranean—although they’re very high at the moment—have been going on for a decade.

What are the major shortcomings you see in the global humanitarian system?

The default response of humanitarian assistance to refugees continues to be focused around refugee camps. Assistance continues to be provided in environments in which refugees don’t have the right to work, often have limited freedom of movement, and get trapped for many years. Refugees increasingly bypass that model: The majority of the world’s refugees now go to urban or peri-urban areas (urban-rural transition zones). And, despite the fact that agencies like the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) have developed fantastic policies on paper, the models to provide assistance to refugees outside camps are struggling.

One of the key things the humanitarian system needs to do better is to empower people to help themselves: to not be dependent on long-term assistance, to have sustainable access to jobs and education. Now, to do that, we need a paradigm shift—one that is not based on seeing refugees just as having vulnerabilities, but one that recognizes their capacities; one that isn’t just focused on seeing refugees as passive victims, but as people with agency. Humanitarian agencies are often good at providing legal guidance and emergency relief, but less good at creating jobs, seeking investments from businesses, and empowering affected communities.

Too often we deny refugees the freedoms and opportunities to participate in the economy and thereby to be perceived as a potential benefit and not necessarily an inevitable burden. To do that, our international system needs to be more open to collaboration with the business sector, with refugee-led organizations, and with civil society organizations.

The UNHCR has appealed for more than $7 billion infunding[PDF], though only about half of that has been met. Where is funding most needed, and how does it affect the livelihoods of refugees?

On the global scale, humanitarian assistance [has increased] in terms of the [aggregate] amount, but relative to need, with what the United Nations calls “Level 3 emergencies” (protracted crises), there is a funding gap. Those shortfalls have serious consequences.

Basic food, clothing, and shelter are being provided at inadequate levels.

Let’s take the Syrian crisis as an example: All of the assistance plans in the region are massively underfunded. In a country like Jordan, educational programs are massively underfunded. In urban areas like Amman, assistance is only focused on the most vulnerable, and only over a quarter of Syrian refugee families are getting cash assistance to support their basic needs.

It also means that in new crises around the world, when you get a mass influx of hundreds of thousands of South Sudanese into a country like Uganda, even basic food, clothing, and shelter are being provided at inadequate levels.

Most refugees fleeing the Syrian conflict today end up hosted by neighboring countries. How can host countries balance providing assistance to refugees and advancing their national interests?

According to UNHCR’s latest data [PDF], 84 percent of the world’s refugees are in developing regions of the world. So countries like Lebanon, Jordan, and Turkey have ended up being disproportionately generous [by hosting the majority of Syrian refugees], and they face the development challenge of having to support a large number of noncitizens.

There is tension between refugees and their host communities in terms of competition for resources. That requires that we provide development assistance that doesn’t just benefit refugees but also hosts. Above all, it requires that we invest in job creation and entrepreneurship that can be mutually beneficial and allow for more sustainable socioeconomic participation until people can go home or move onward.

For societies that could be overwhelmed, we have to maintain a commitment to resettlement. The United States has historically been the largest resettlement country in terms of taking people out of camps and providing them with organized resettlement and a pathway to citizenship. More countries need to contribute to that effort. We need to ensure that there’s a managed route that doesn’t rely on people using smugglers and embarking on dangerous journeys.

How legitimate are national security concerns cited by different countries when it comes to admitting or excluding refugees?

The relationship between refugees and terrorism is exaggerated by the media and by populist politicians. In the United States, for instance, the empirical relationship doesn’t bear out any kind of correlation between the presence of refugees and the likelihood of a terrorist attack. Refugees are rigorously checked in their status-determination processes [by UNHCR]; they are even more rigorously checked [by domestic agencies] when resettling in parts of the world like the United States and Europe.

We have to distinguish the situation in Europe and North America ... from the very real fears [in the Middle East].

But occasionally terrorist organizations seek to exploit the movement of vulnerable people across borders. That’s why some countries like Jordan and Lebanon have closed their borders, which has had terrible consequences for refugees’ access to protection but has been understandable given the presence of the Islamic State and [the Syrian al-Qaeda affiliate formerly known as Jabhat] al-Nusra on the other side of the border. I think we have to distinguish the situation in Europe and North America, where there is very little correlation between refugees and terrorism, from the very real fears of countries [neighboring Syria].

Some states have implementedspecial economic zones(SEZs), in which refugees can be educated and trained to work, to alleviate the refugee crisis. How viable is this strategy?

The key to creating sustainable solutions for refugees is to move beyond warehousing people indefinitely year on year. In Uganda, the government gives refugees the right to work and freedom of movement. In Kampala, for instance, 21 percent of refugees run a business that employs at least one other person, 40 percent of whom are nationals of the host country. The problem is that not every host country is prepared to adopt the Ugandan model. We need to look to alternative solutions in more politically constrained environments.

Jordan is an example of a politically constrained environment. For a long time it placed huge de facto restrictions on Syrians’ right to work. That has meant that Syrians ended up in camps without the right to work in the formal sector, or they had to go to urban areas and face significant exploitation in the informal economy.

Jordan needed labor and foreign direct investment; that led to what became known as the Jordan Compact [PDF]. With support from the World Bank, trade concessions from the European Union, and bilateral development aid from the United Kingdom and other donors, Jordan has committed to providing two hundred thousand work permits to Syrian refugees. To date, Jordan has allocated over fifty thousand work permits under that scheme, taken people out of the informal sector, and opened access to the minimum wage and labor protections.

Syrian factories have relocated to the SEZ and employed Syrians and Jordanians alongside one another. The challenges that the Jordanian model has seen include a lack of international investment to create new jobs. So, although corporations like Walmart and IKEA have done supply-chain investment through factories in the zone, there’s been a lack of incentive for business to relocate manufacturing operations. To achieve that, a stronger pitch needs to be made that relocating manufacturing to a country like Jordan is not just useful on a corporate social responsibility basis, but also it makes good business sense. When the wars finish in Iraq and in Syria, businesses located in Jordan will have access to that wider market. SEZs are not a panacea in creating socioeconomic opportunities for refugees, but they are a worthwhile idea to pilot alongside other context-specific responses.

If the refugee regime is to shift to one focused on integration and economic development, what are some of the hurdles governments and communities might face?

In the data we’ve collected, around 38 percent of the Syrian [refugees in Europe] have a university degree. But, on the other hand, there are huge levels of unemployment; around 87 percent are unemployed. Now the question is, why is it that you can have a population that has skills and talents and yet such little access to jobs? The language barriers are significant; that’s by far the most challenging gap. But there’s also a lack of recognition of qualifications, there are sometimes skills gaps that need to be updated, and there are sometimes information gaps in how to navigate the job market.

Why is it that you can have a population that has skills and talents and yet such little access to jobs?

When refugees are resettled to the United States, they have a one-year clock that ticks down. They get support for that period, but thereafter they have to be independent. Within that time, they need to have access to transportation, they need to have access to language skills, they need their qualifications recognized, and they need to understand how to get their kids into the school system.

When we get to the developing countries, there is a whole series of potential additional barriers to participation that may include xenophobia, legislative restrictions in terms of the right to work, and simply the lack of basic infrastructure, including things like connectivity to the internet, electricity, and roads.

This interview has been edited and condensed.