How Did China Manage its Currency Over the Summer?

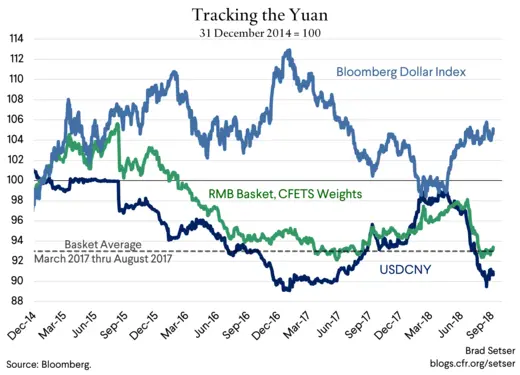

China still manages its currency. That’s hardly a shocking statement, I know. But I don’t fully subscribe to the view that China’s depreciation in the summer was simply a market move, given the dollar’s broad strength.

If China’s currency appreciates, that means that China’s authorities decided to allow the appreciation—and not enter the market to block “market” pressure to appreciate.

And if China’s currency depreciates, that means that China’s authorities decided to allow the depreciation, and not enter the market to block “market” pressure to depreciate.

The key isn’t the market pressure, at least not on its own. It is the decision by Chinese authorities to allow the market pressure to push the currency to a new level.

That’s why—as the Economist’s Buttonwood notes this week—there is real information value in the price of the yuan.

“When the yuan moves, it carries rare news— about currency demand, about China and by extension about the world economy.”

And that’s also why there is information in the scale of China’s intervention in the foreign exchange market. If China is resisting market presure, in either direction, it should show up somewhere on the state’s balance sheet.

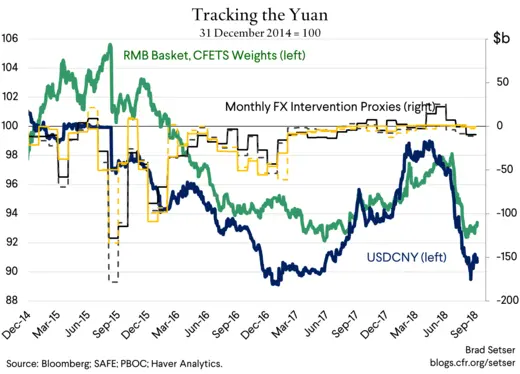

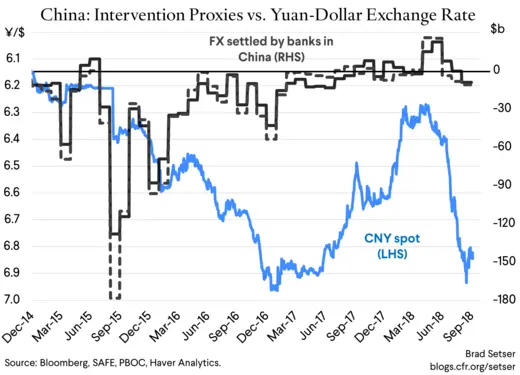

Those proxies for China’s true intervention are currently telling two stories:

- China is still using intervention—though on a more modest scale than in the past—to help define the yuan’s trading range (against the basket I assume).

- China’s intervention is currently being done in a less transparent way than in the past, as it is largely coming through the state banks rather than the PBOC.

The most straightforward way to assess China’s intervention is to look for changes in the value of the foreign exchange reserves the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) reports on its balance sheet. Those reserves are reported at historical purchase cost. The change in the reserves thus provides a measure of intervention.

And the PBOC’s balance sheet (the changes in the PBOC’s balance sheet are the yellow line on the graph) has been absolutely flat this year.

Too flat in a way.

It isn’t clear, for example, what is happening to the interest income that China receives on its massive stock of reserves. It doesn’t seem to be entering into the PBOC’s balance sheet in any obvious way these days. You would think the PBOC’s balance sheet would be growing by something like $50 billion a year just based on the interest on its reserve stocks.*

The activity over the spring and summer has showed up only in the settlement data (the black line in the graph)—a data set that aggregates the activities of the state banks and the PBOC. The easiest interpretation of a gap between the “settlement” data and the PBOC balance sheet is that the gap reflects the activities of the state banks (before 2015, China published a useful data series on the foreign exchange position of the banking system—but, alas, that data series disappeared after the August 2015 depreciation. I still miss it…)

And it looks like the state banks bought $20 billion of foreign exchange in both April and May. That in effect set a cap on how far the Chinese would allow the yuan to appreciate.

The state banks then sold some dollars forward in July, and also sold about $10 billion in foreign exchange in August.

That—along with other signals from the Chinese authorities (the counter-cyclical factor, the increase in the reserve ratio on forwards, a rising premium in the offshore forward market that raised the cost of shorting the yuan) helped end the depreciation of June and July.

The yuan now looks to be effectively managed against a basket, with an (undeclared) band between say 92 and 98 on the CFETS basket. That at least is what I would infer from China’s pattern of intervention over the last 18 months.

There is one other point that is worth making: while China still intervenes to manage its currency, the amount of intervention that has been required to keep the yuan within the authorities’ band has been pretty modest recently. By Chinese standards, $10-20 billion a month is nothing…

That reflects the fall in China’s current account surplus. The surplus in manufactures remains large, to be sure (as the IIF’s Robin Brooks has emphasized). But higher commodity prices have reduced (for real) the overall goods surplus. And more tourism and changes in the way tourism spending abroad is estimated have dramatically increased China’s tourism deficit.** There isn’t a massive gap between export proceeds and imports (so long as the tourism “imports” are all real).

And over the last year, the financial account has generally been close to balance. Cracking down on Anbang and HNA led to a big fall in outward FDI. Sizable inflows into Chinese government bonds have helped to balance ongoing private outflows (which show up in the errors and omissions line). And the banks, in aggregate, are now borrowing abroad to fund much of their lending abroad. They no longer are generating a net outflow.

That makes China’s decision about how to manage the yuan as the United States escalates its tariffs—with a potentially giant increase in January—all the more interesting.

A weaker yuan is the obvious way to offset a negative export shock, and it is an easy way to try to counter the Trump administration’s actions—especially once China is in a position where it cannot match Trump’s tariffs dollar for dollar.

But letting the yuan go through the bottom edge of the range that the PBOC has—more or less—established over the past two and a half years might upset expectations. There was a sense over the summer that China would likely step in to limit depreciation at the 91 or 92 market (on the CFETS basket) and at around 6.9 to the dollar. That helped keep the broader market calm.

If the yuan were to fall through those barriers, there isn’t an obvious limit to how far it could fall. Global markets might get nervous.

Finally, letting the yuan weaken would put a lot of pressure on other emerging market currencies. China doesn’t have a lot of foreign currency debt, at least not relative to the size of China’s economy (the banks are borrowing abroad to lend abroad, so they are hedged; some property firms though aren’t and could be in trouble). But some other emerging markets do have a problem with foreign currency debt and wouldn’t welcome a Chinese decision that puts further pressure on their currencies.

And, well, letting the yuan weaken in response to U.S. tariffs helps China export more to Europe and Japan—and they might not put all the blame for a new China exchange rate shock on the United States.

Makes for an interesting choice.

Even though China doesn’t meet two of the three criteria that the U.S. Treasury has set out to evaluate when exchange rate management crosses the line and becomes manipulation,*** the way China manages its currency still matters for the United States—and for the world.

*It would be great if the interest income was sold for CNY and remitted back to the budget—that’s what I think countries with large reserves should do. Yet the balance of payments data has shown $20-30 billion in reserve growth a quarter ($110b, or almost a percentage point of GDP, in the last four quarters of data), and the most obvious explanation for the difference with the PBOC’s balance sheet is that interest income isn’t entering into the PBOC’s ticker. That then raises the question of how interest income does enter into the balance sheet…

**I was looking back to see if China’s current account surplus exceeded 3 percent of GDP in 2014 and 2015. That’s the U.S. Treasury’s threshold for assessing manipulation these days. It now doesn’t. But it did back at the time. The $100 billion jump in China’s tourism imports in 2014 (from methodological changes in the compilation of the balance of payments data) came at a very convenient time.

***There is a conceptual difficulty with Treasury’s criteria that is worth noting. The criteria were developed to capture countries that blocked appreciation through heavy intervention—a coherent, clear definition of manipulation that hasn’t been consistently applied in the past. They won’t capture a country that in effect manages its currency down—as the process of carrying out a managed depreciation burns through reserves. Think of it this way: if China let its currency depreciate to 90 vs. the basket (or 7 vs. the dollar), Chinese residents might start to expect that China wanted further weakness, and move funds out of the yuan. Controlling the depreciation, once it gets started, can require selling a lot of reserves—and the 2015 definition of manipulation is entirely focused on reserve purchases. I suspect that this would prompt the Trump administration to dust off the 1988 definition of manipulation (weakening a currency to gain a competitive advantage in trade). But that too has problems, as China could respond to concerns that it is guiding its currency down by just letting the yuan float down…the reality now, I think, is that it is in the United States’ interest for China to continue to manage its currency for a while longer.