The Root of China’s Growing Youth Unemployment Crisis

More on:

China’s exports fell in August for the fourth month in a row, putting yet more pressure on its government to boost domestic consumption—something it has pledged, but thus far failed signally, to do.

Reviving a flagging economy is of great political importance for the Chinese Communist Party, not least because of the risk that the younger generation will question the legitimacy of a system that cannot meet its basic aspirations for gainful employment. Yet the signs are that their prospects will continue to deteriorate.

The youth unemployment rate (for those aged 16 to 24) hit a record-high 21.3 percent in June, following which the government announced that it would no longer publish the statistic. To juice the economy and create jobs, it is pulling the levers it knows best: home-buying incentives and infrastructure investment—the latter of which expected to total $1.8 trillion this year.

Unfortunately, the increasingly state-dominated property and construction sectors are not only notoriously unproductive, but virtually irrelevant to the prospects of the young and the educated. Young Chinese look overwhelmingly to the service sector, which employs half the national workforce, for jobs. And so new stimulus-driven opportunities in fields such as carpentry and bricklaying hold no interest for graduates in areas such as literature and computer science.

For decades now, the Chinese government has encouraged university enrollment, pushing the number of students in higher education from 22 million in 1990 to 383 million in 2021. During the pandemic, it pressed even harder, expanding graduate-school capacity. Master’s-degree candidates rose by 25 percent in 2021. China’s Ministry of Education estimated that 10.76 million college students would graduate in 2022, 1.67 million more than in 2021—and it expects a further large rise in 2023.

More on:

Meanwhile, the service industry, beaten down by party-ideological policies aimed at controlling the activities and growth of private-sector firms in areas ranging from tech to tutoring, suffered a sharp downturn in 2020. After showing brief signs of recovery in the first quarter of this year, a broad measure of services activity fell in August to an eight-month low.

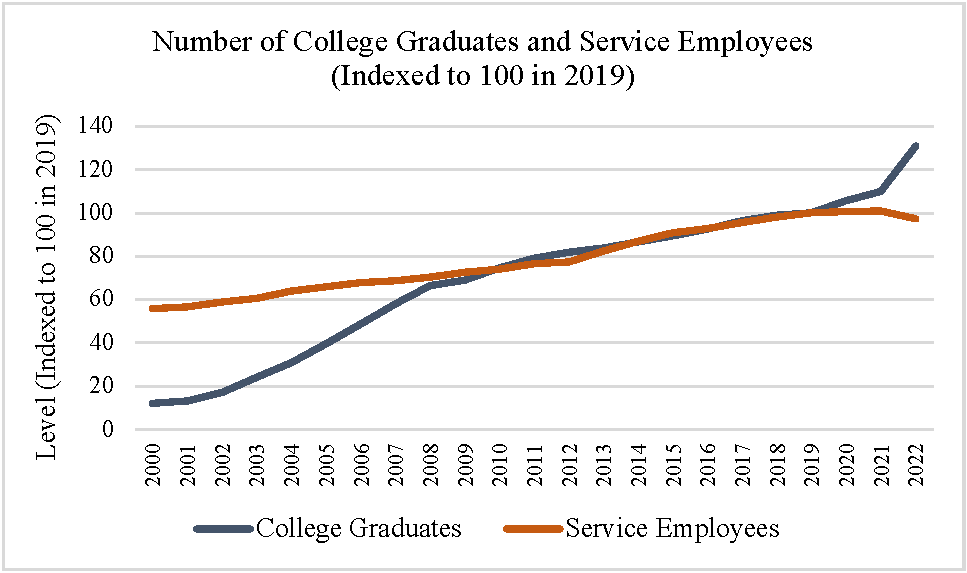

Unsurprisingly, a huge gap has opened between growth in the number of college graduates, the level of which now being far above its pre-pandemic level, and growth in the number of service jobs, the level of which having flattened out during the pandemic and fallen last year. This gap can be seen in the top graphic above. The bottom graphic shows the difference between year-on-year growth in the number of service jobs and the number of college graduates. That gap grew enormously in 2022, and, with a record numbers of students taking China’s college-entrance exam this year, looks set to remain wide.

The message for China’s policymakers is clear: boosting graduate numbers while throttling services and subsidizing building is bad economics and worse social policy. It will further distort China’s imbalanced economy, and fuel discontent among an age cohort on which China will depend for its future national vitality.

Online Store

Online Store