Global Climate Policy After Paris

As countries prepare to sign the landmark Paris climate accord, the work to reduce global carbon emissions is only beginning, says CFR’s Michael Levi.

By experts and staff

- Published

By

- Michael LeviDavid M. Rubenstein Senior Fellow for Energy and the Environment and Director of the Maurice R. Greenberg Center for Geoeconomic Studies

- James McBrideDeputy Managing Editor

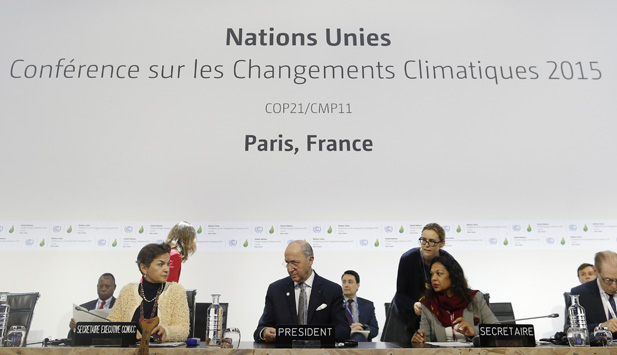

The Paris Agreement on climate change, accepted by 195 countries in December 2015, creates a new framework for reducing global greenhouse gas emissions in which each country sets its own voluntary targets, to be ratcheted up every five years. On April 22, 2016, the accord opens for signing at the UN headquarters in New York, but this is only the beginning of the process, says CFR Senior Fellow Michael Levi. “The Paris climate talks resolved some very important issues, but left some equally important ones to future summits,” he says. At the same time, political volatility around the world, uncertainty over the legality of U.S. carbon regulations, and plunging oil prices have all complicated the climate picture.